Disability Rights California Self-Help Guide for Tenants Facing Eviction

Disability Rights California Self-Help Guide for Tenants Facing Eviction

This guide provides general information to help prepare litigants (people who go to court without an attorney) to understand the unlawful detainer (also known as “eviction”) process. The unlawful detainer process is the legal process a landlord must go through to evict a tenant.

This guide provides general information to help pro per litigants (people who go to court without an attorney) understand the unlawful detainer (also known as “eviction”) process. The unlawful detainer process is the legal process a landlord must go through to evict a tenant. While this guide cannot cover every possibility in unlawful detainer actions, it is written to help give a basic understanding of a tenant’s rights during the process. The table of contents, unlawful detainer process flowcharts, and narrative description (found in Section 1, entitled “General Overview”), provide big picture references to refer back to as you navigate this guide.

If you are a tenant who needs help, you can contact your local court’s self-help center, where you can get assistance filing court forms, including those required in the unlawful detainer. The court’s self-help center cannot give you legal advice, but it can give you information on other legal organizations that might be able to represent you or give you legal advice.

Find your local court’s website and self-help center information here: https://www.courts.ca.gov/find-my-court.htm?query=browse_courts.

NOTE – sometimes in eviction cases, the landlord may have hired an attorney to represent them. Because of this, throughout this guide, the term “landlord/landlord’s attorney” will be used to mean the landlord if the landlord does not have an attorney, or the landlord’s attorney if the landlord does have an attorney.

Disability Rights California is committed to the inclusivity and visibility of transgender/gender-variant/intersex people. We use “they/them/their” pronouns in this document to be inclusive of all Californians.

This publication is not legal advice and is not a substitution for legal advice.

Table of Contents

- General Overview

- Responding to the Summons and Complaint–the Answer and other Court Forms

- Settlements and Mediation

- What is a settlement and how do I ask for one?

- Common settlement agreement examples

- If a settlement is not reached - Relief from Forfeiture and Stay of Eviction

- What is alternative dispute resolution and mediation?

- Cost

- How does a tenant know if mediation or another dispute resolution service is offered or required at their court?

- What will happen during the mediation?

- Confidentiality

- Who is the mediator?

- What is the outcome of mediation?

- Why participate in mediation?

- What if a tenant needs a reasonable accommodation to participate in mediation?

- Discovery

- Unlawful Detainer Discovery Timeline

- How does a tenant send their responses to the discovery requests?

- What happens if a party does not respond to discovery requests or makes false statements in the responses?

- How much time does a tenant have to respond to discovery requests?

- What is the point of discovery responses?

- What are the different kinds of discovery?

- Reasonable accommodations

- Objections to Discovery Requests

1. General Overview

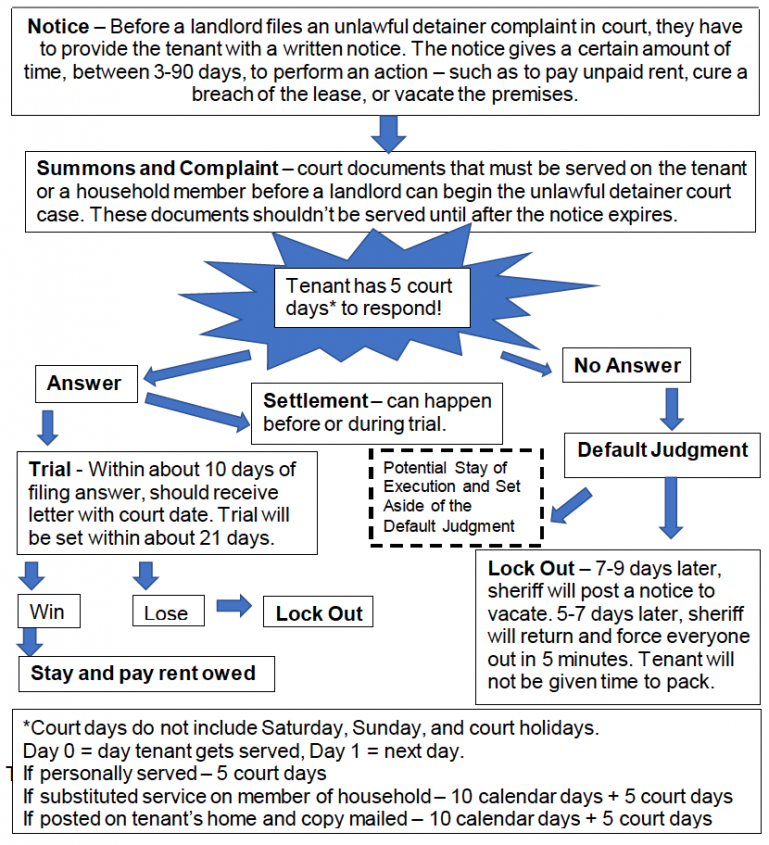

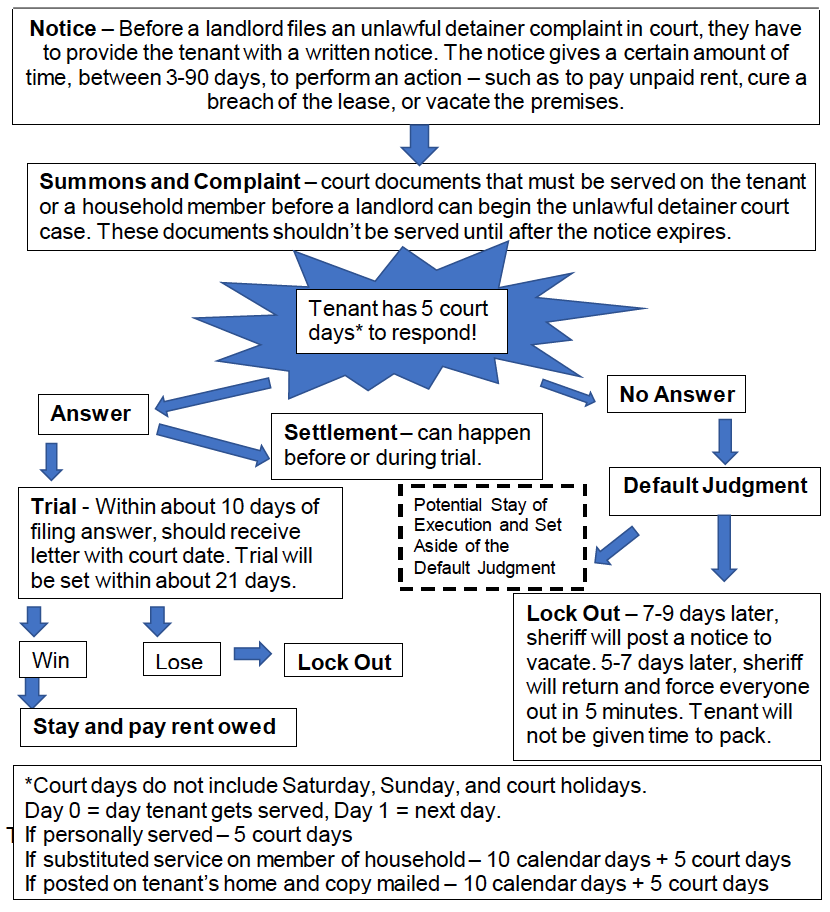

1.A. Eviction (Unlawful Detainer) Process Flowchart

NOTE: This section describes what is supposed to happen when a landlord follows the eviction laws. If you are unsure whether your landlord is following the eviction laws, you should consult with an eviction defense attorney.

1.B. Eviction (Unlawful Detainer) Process- Narrative Version

NOTE: This section describes what is supposed to happen when a landlord follows the eviction laws. If you are unsure whether your landlord is following the eviction laws, you should consult an eviction defense attorney.

Step 1 Notice from Landlord – Before a landlord files an unlawful detainer complaint in court, they have to provide the tenant with a written notice. The notice gives a certain amount of time, between 3-90 days, to perform an action – such as to pay unpaid rent, “cure” (fix) a breach of the lease, or “vacate” (move out of) the premises. If you have questions about COVID-19 eviction protections for unpaid rent, and special notice rules visit: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/post/coronavirus-housing

Step 2 Summons and Complaint – These are court documents that must be “served on” (or given to) the tenant or a household member before a landlord can begin the unlawful detainer court case. These documents should not be served until after the notice period expires. WARNING – once the tenant receives the summons and complaint, the tenant has 5 court days* to respond with an “answer,” which is a court form, and file it with the court. The local court’s self-help center can help tenants fill this form out. Local court’s website and contact information can be found here: https://www.courts.ca.gov/find-my-court.htm?query=browse_courts

* Court days do not include Saturday, Sunday, and court holidays. Day 0 = day tenant gets served, Day 1 = next day. If personally served, a tenant has 5 court days to file the answer. If the complaint and summons were served on member of household (“substituted service”), 10 calendar days + 5 court days to file an answer. If posted on the tenant’s home and copy mailed, 10 calendar days + 5 court days to file an answer.

Step 3.A. If the tenant did not file an Answer – Default Judgment and LOCK OUT.

A default judgment can be ordered by the court against the tenant if they did not file an answer to the complaint and summons. This means the tenant is automatically evicted without a trial. 7-9 days after the default judgment, the sheriff will post a notice to vacate, and 5-7 days later, the sheriff will return and force everyone out in 5 minutes. The tenant will not be given time to pack. There are potential forms of relief known as “stays of execution” and “set asides” if there is a legal reason for why the eviction should not take place. However, these forms of relief are rare and fact specific, so tenants should consult with an eviction attorney.

Step 3.B. If the tenant filed an Answer – Settlement or Trial

Settlement – the tenant and landlord make an agreement.

OR

Trial - Generally, within about 10 days of filing the answer, the tenant should receive a letter with a court date. The trial will be set about 21 days after the tenant files an answer. However, a tenant should not assume that they will receive a timely notice, so they should proactively check with the Court to find out their trial date.

If the tenant loses at trial – The Tenant Gets Locked Out – same notice posting procedure and lock out timeline described under Step 3.A.

If the tenant wins at trial – The Tenant Stays and Pays Rent Owed.

2. Responding to the Summons and Complaint–the Answer and other Court Forms

This section explains forms that are commonly filed with the court after a tenant receives the summons and complaint. There are also links that provide additional resources on how to fill out the forms, and where to get additional assistance. This section will provide more information on the following forms:

- Answer

- Attachment to the Answer (optional)

- Proof of Service

- Demand for Jury Trial (optional)

- Fee waiver (optional)

Answer:

To respond to the landlord’s claims against them in the summons and complaint, a tenant may file an “answer” with the court to:

- deny any false statements made by their landlord in the complaint, and

- state any defenses they may have to the eviction.

If no response to the complaint is filed, the judge or clerk can order a default judgment, and about 12-14 days later, the sheriff can lock the tenant out of their home.

The Court has created an answer form. The blank form can be found here: https://selfhelp.courts.ca.gov/jcc-form/UD-105.

Detailed instructions on how to fill out the answer form can be found here: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/system/files/file-attachments/Link_4_UD_105_Instructions.pdf, in our guide about how to answer an eviction lawsuit found here: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/publications/fact-sheet-how-to-answer-an-eviction-lawsuit.

A short tutorial video online that shows tenants how to complete the answer form can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZNb3WVFo8s.

Once the tenant files the answer with the court, the tenant ”serves,” or delivers, a copy of their answer on their landlord (see “Proof of Service” section below).

Attachment to the Answer (optional):

Some tenants include additional legal defenses that are not listed on the court’s answer form by filing an attachment with their answer. A template attachment can be found here: Attachment 3l Attachment StateWide (pdf). After reviewing the attachment and the defenses carefully, a tenant can check off the boxes they think apply to them. This PDF can also be found in DRC’s guide on how to answer an eviction lawsuit here: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/publications/fact-sheet-how-to-answer-an-eviction-lawsuit.

Proof of Service:

A copy of the answer needs to be served (delivered) to the landlord or the landlord’s attorney. In California, a tenant can serve documents to their landlord by mail. The service needs to be done by someone over the age of 18 that is not involved in the eviction lawsuit. That person needs to complete and sign a “Proof of Service” form.

A blank “Proof of Service” form can be found here: https://selfhelp.courts.ca.gov/jcc-form/POS-030. Detailed instructions on how to complete this “Proof of Service” form can be found on the backside of the Proof of Service form and also here: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/system/files/file-attachments/Link_7_POS_Instructions.pdf.

CAUTION: After completing the service, the tenant needs to file both the completed “Proof of Service” and the original “Answer” form with the court.

Demand for a Jury Trial:

Tenants have the option of having their case decided by a jury, which is a group of people from the public who decide the case, or by a judge. A trial with a jury, is called a jury trial, and tenants who want a jury trial have to request it in advance. A trial decided by the judge and without a jury is called a “bench” trial. There are both advantages and disadvantages to jury trials and bench trials. If a tenant isn’t sure of which one to pursue, they can consult with an eviction attorney.

If a tenant wants a jury, rather than a judge, to determine the outcome of their case, they can request to have a jury trial in their “answer,” or they can file a separate document. This is the court’s standard form to request a jury trial: https://selfhelp.courts.ca.gov/jcc-form/UD-150. A template Word document that can also be used to request a jury trial is attached here: Demand for Jury Trial Template (docx). A tenant can fill in the bracketed and highlighted sections and edit either form before filing with the court.

If a tenant decides to request a jury trial in a separate document, rather than in their answer, they will need to serve a copy of this document to their landlord or their landlord’s attorney, and file the original copy with the court. See “Proof of Service” section above for instructions on how to complete service and prepare and file a proof of service form.

Request a Fee Waiver:

There are court costs that need to be paid to file documents with the court. Tenants can request a fee waiver if they cannot afford the fee by filling out the necessary forms.

Blank copies of the three fee waiver forms can be found here:

- https://selfhelp.courts.ca.gov/jcc-form/FW-001;

- https://selfhelp.courts.ca.gov/jcc-form/FW-002;

- https://selfhelp.courts.ca.gov/jcc-form/FW-003.

Detailed instructions on how to fill out these forms can be found here: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/system/files/file-attachments/Link_9_Instructions_on_FW_Forms.pdf.

NOTE: The “FW-002: Request for Waive Additional Fees” should only be completed and filed if a tenant is requesting a jury trial, otherwise the tenant only needs to file form “FW_001 Request to Waive Court Fees” and “FW_003 Order on Court Fee Waiver.”

NOTE: a tenant does need to serve copies of the fee waiver forms to their landlord or their landlord’s attorney, they only need to file them with the court.

Where to Get Help

If a tenant needs help filing their answer, or any other forms, they can go to their court’s local self-help center, or eviction defense legal aid provider.

Contact information for local courts can be found here: https://www.courts.ca.gov/find-my-court.htm?query=browse_courts.

A referral sheet for eviction defense legal assistance can be found here: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/system/files/file-attachments/Link_13_Housing_Law_List_2020-with_SR_edits.pdf.

What Happens After a Tenant files their Answer?

Within about 10 days of filing an answer, the tenant should receive a letter with a court date. Their trial will be set in about 21 days. After that, eviction lawsuits will generally be resolved by either a settlement or a trial. See the following sections to learn more about each of these processes.

3. Settlements and Mediation

This section provides information on three ways an eviction lawsuit may be resolved without having to go to trial – settlements, alternative dispute resolution, and mediation. All three of these processes can be useful tools for both parties in the eviction process to reach an agreement without having to go through the stress, time, and uncertainty of trial. This section begins by describing what settlements are, how to go about asking for a settlement, things to consider when coming to a settlement agreement, and some common settlement examples. This section ends with some possible forms of relief if a settlement is not reached, and information about alternative dispute resolution and mediation.

What is a settlement and how do I ask for one?

A settlement agreement is a way that parties – in this case, the tenant and their landlord in an unlawful detainer lawsuit – can resolve the lawsuit on their own, instead of having a judge or a jury decide at trial.

Some courts require the parties to participate in what they call a “mandatory settlement conference” which generally takes place before the trial begins. Mandatory settlement conferences can be very informal. For example, they can be a five-minute conversation between the parties in the hallway outside the courtroom. Or, they can be more formal, and take place in the courtroom with the judge guiding the conversation.

Because landlords who have entered into the eviction process have typically invested money in it – by paying court and possibly attorney’s fees – it is not common for landlords to approach tenants for settlement on their own. However, it might be beneficial for the landlord to settle, instead of spending more money on a trial. For these reasons, if a tenant is interested in settling the case, instead of fighting it at trial, a tenant may want to approach their landlord to ask for a settlement. Even if the court has required a mandatory settlement conference, a tenant may still attempt to settle the case with their landlord before the conference.

Settlement negotiations can begin with an informal conversation or with an offer that starts the two sides sending offers back and forth. For example, a tenant can make an offer, and the landlord or the landlord’s attorney will respond with a yes or no. The landlord may also make a counter-offer to the tenant’s offer, and the tenant can accept this, reject this, or make their own counter-offer.

Because it is easier for the parties to know what each side promised to do if it is in writing, tenants and landlords usually put their agreements in writing, include every important term to them, and make sure both the tenants and the landlords have signed it. That way if one side does not do what they agreed to do, the other side can go to court for help. (See below for example settlement terms.)

If it appears that the tenant won’t be able to reach an agreement with their landlord, they can defend themselves at trial with the judge or jury. NOTE – because of California Evidence Code §1152, offers to settle the case cannot be used against someone in court.

Common settlement agreement examples:

- Negotiate a Move Out: If a tenant wants to move out, here are some items to consider in negotiating a settlement agreement:

- Time: Tenants ask for the time they need to move out, knowing that the landlord will try to negotiate it down to a shorter time. Example – if a tenant could likely move out in 30 days, a tenant may want to ask for 60 days. Or if a tenant knows they need 60 days, they may want to ask for 90 days.

- Past Due Rent: Tenants can negotiate a waiver, or forgiveness, of rent owed, attorney’s fees, and court costs. Sometimes landlords only want to get the apartment back and will agree to give up the rent tenants owe if they move out. Tenants can also ask the landlord to agree to waive any rent that they owe, if, for example, they did not pay the rent because their apartment was in bad condition and the landlord did not fix the problems.

- Security Deposit: Tenants can consider giving up their security deposit in exchange for waiving or lowering the amount of any rent or other fees owed.

- No Eviction on Record: Tenants can negotiate to make sure their court record is sealed. This will prevent the eviction from showing up on public records and harming their credit or making it hard for them to rent an apartment in the future.

- Negotiate a Pay and Stay:

If a tenant wants to stay, and the reason for the unlawful detainer is because of unpaid rent or other fees, the tenant will likely have to pay a full or partial payment amount of the unpaid rent or other fees to stay in the unit.

In the initial complaint, the landlord will likely ask the tenant to pay all or most of the owed rent, attorney’s fees, and court costs. The tenant may be able to negotiate either a waiver, or forgiveness, of these costs, or a lower amount to pay. Here are some items to consider in these kinds of negotiations:

- Full Payment: Tenants can pay all the requested money in exchange for a dismissal.

- Payment Plan: Tenants can request a payment plan if they don’t have all the requested money. Caution, if tenants miss a payment on a payment plan, they may be evicted without further notice.

- Waiver/Forgiveness: Landlords may be more likely to forgive past due rent, fees, and costs if tenants have defenses or the landlord wants to keep the tenant. For example, if a tenant did not pay the rent because their apartment was in bad condition and the landlord did not fix the problems, the tenant may ask the landlord to let them pay less rent until repairs are made, then pay their regular amount of rent when the apartment is fixed.

- No Eviction on Record: Tenants can negotiate for dismissal to be entered in court, and for the court to seal their case records.

CAUTION: if a tenant does not follow the terms of the settlement agreement, they might be evicted.

If a settlement is not reached - Relief from Forfeiture and Stay of Eviction

If the tenant was unable to reach a settlement, before their trial starts, they can still ask the judge to be able to pay everything owed so they can stay in their unit. People typically ask for “Relief from Forfeiture” (Code of Civil Procedure §1179) if they have experienced a hardship, but have no legal defenses. To qualify for this relief, a tenant must:

- Have all the rent owed by the trial date;

- Be realistically able to pay all future rent; and

- Be able to pay attorney’s fees, court costs, and other costs.

If a tenant was unable to reach a settlement, and has been ordered evicted by the court, a tenant can also request that the court “stay” (or hold off) the eviction for up to 40 days, but the landlord can demand payment for those 40 days. (CCP §1176.) Note, a tenant can only request a “stay of execution” if the landlord is present on the trial date or they have given ex parte notice (advance notice in writing) to the landlord. A tenant can check their local court procedures with the courtroom clerk or on the local court website if they have questions about how to give notice for a “stay.” If a tenant is requesting a “stay of execution” because of extreme hardship, the tenant should bring all of their records and other evidence that prove the hardship to court. For example, the tenant could bring medical records showing when they were in the hospital.

What is alternative dispute resolution and mediation?

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is the term used for all ways to resolve lawsuits that do not include a trial or a court decision. Some ADR processes may be optional or very informal, others may be mandatory and formal.

Mediation is one type of alternative dispute resolution. Mediation is a formal discussion with both sides of a lawsuit in an effort to attempt to resolve all or part of a lawsuit.

Cost

If the court provides mediation, there is no cost to participate in mediation. However, if the landlord brings an attorney to the mediation, this will increase the landlord’s attorney’s fees, which the tenant may be responsible for.

How does a tenant know if mediation or another dispute resolution service is offered or required at their court?

A tenant should check with their local court’s self-help center or legal aid agency to find out their court’s local practices and any requirements for mediation or other forms of alternative dispute resolution.

What will happen during the mediation?

A mediator will talk with both sides to help them understand one another’s views. At times, both parties may be in the room together with the mediator, at times only one party may be in the room with the mediator.

Confidentiality

The discussions during mediation are confidential and cannot be used as admissions in court. The only exception to the discussions being entered in court is during a criminal proceeding. Cal. Evidence Code 1119.

Who is the mediator?

The mediator is a specially trained third party. The mediator is not a judge, but is sometimes an attorney. Even if one side is 100% wrong and one side is 100% right, the mediator will not take either party’s side. The mediator is neutral. The mediator will not decide the lawfulness or fairness of the dispute. The mediator will ask questions of each side to try to come to an agreement between both parties.

What is the outcome of mediation?

Just like with negotiated settlements, if a tenant reaches an agreement on all or part of a dispute, it would be best if they put their agreement in writing. The agreement should include terms about how the lawsuit is supposed to be resolved (for example, include terms about permanently sealing the eviction court record per California Rule of Court 2.551 even if the mediation takes place outside of a courtroom). Caution – a tenant does not have to accept the settlement terms that the landlord/landlord’s attorney or the mediator suggest. If the tenant does not reach an agreement, their case will return to court as if the mediation had never happened.

Why participate in mediation?

If a tenant has had a hard time trying to resolve their case with their landlord, a mediator may be able to help the tenant communicate with their landlord. If the tenant does not reach an agreement, they can still go trial. Even if a tenant does not reach an agreement, the tenant might – through the mediation process – learn what is important to the other side to resolve the lawsuit, which may help the tenant to eventually settle.

What if a tenant needs a reasonable accommodation to participate in mediation?

If the tenant’s court provides mediation, they can refer to the Section 8 entitled “Reasonable Accommodations in Court.”

4. Discovery

Discovery is the word for the legal process in a lawsuit, where the parties – in this case the tenant and their landlord – ask each other for documents, information, and admissions. Both parties in a lawsuit want this information from the other side so that they can use it at trial to try and prove their case, or use it to try to negotiate a settlement before trial.

The following section provides information on the discovery process – including the steps and timelines for discovery, descriptions and examples of the different kinds of discovery requests, and objections that can be made to discovery requests.

CAUTION - all responses to discovery requests must be verified. This means that the tenant will have to sign, under penalty of perjury, that all of the information provided in the document is accurate and that their responses are true and correct.

Unlawful Detainer Discovery Timeline

Discovery begins:

- 5 days after the landlord serves the tenant with the summons and complaint OR

- 5 days after the tenant has filed an answer to the unlawful detainer lawsuit, whichever happens first.

Discovery must be completed:

- five calendar days before trial.

CAUTION – both parties are required to respond to discovery that was correctly served on them. To avoid severe consequences, a tenant in the discovery process should prepare and serve responses to these requests prior to the legal deadlines.

A tenant and their landlord can also agree to different discovery deadlines. However, if they do agree to a different discovery deadline, it would be best if the agreement is documented in writing by email, text, or letter.

How does a tenant send their responses to the discovery requests?

A tenant must have someone else mail the responses (“serve”) and sign the proof of service. The proof of service is a written declaration that the person served or delivered paperwork to someone. The person who serves and signs the proof of service for the tenant must be a resident or employee in the county where the mailing occurs and must be age 18 years of age or older (refer to “Proof of Service” in Section 2).

What happens if a party does not respond to discovery requests or makes false statements in the responses?

The judge may order fines against the party, find the party in contempt of court, order the party to pay the other side’s attorney fees, or rule on the case before trial has happened.

How much time does a tenant have to respond to discovery requests?

There are different timelines, depending on how the tenant received the request:

- If someone serves the discovery requests to the tenant in person, the tenant has 5 calendar days from the date they were served to respond.

- If someone sends the tenant the discovery requests by overnight delivery, the tenant has 7 days from the date the requests were mailed to respond.

- If someone sends the tenant the discovery requests via regular mail, the tenant has 10 days from the date the requests were mailed to respond.

NOTE – the landlord also has 5, 7, or 10 days from the date the tenant served discovery to respond to the tenant’s discovery requests, depending on the tenant’s method of service (personal, overnight, or regular mail), outlined above.

What is the point of discovery responses?

Responses may be used to raise questions about the responding party’s truthfulness or believability, or to introduce, or put limits on, what issues can be brought to the judge’s attention during the trial. This is why it is important to respond to discovery, access legal counsel if possible, and make sure the other side is following the rules in its discovery request.

What are the different kinds of discovery?

There are five kinds of discovery:

- Interrogatories – written questions that must be responded to in writing.

- Requests for Production – requests to review documents or physical evidence.

- Requests for Admission – requests to have a fact admitted as being true.

- Depositions – in person interviews about the facts of a case.

- Subpoenas – a way to ask for documents, information, or an interview of, or from someone who is not a party to the lawsuit.

Each type of the 5 types of discovery is explained in more detail below, with examples.

- Interrogatories – written questions that must be responded to in writing. Generally, either side may only serve 35 interrogatories on the other side. Code of Civil Procedure 2030.30. However, in unlawful detainers there are “form” interrogatories, which tenants will need to answer all requests, even if there are more than 35.

NOTE – in the unlawful detainer lawsuit, the landlord is the “plaintiff,” or the party bringing the case, and the tenant is the “defendant,” the party who the case is being brought against.

Here are examples of common interrogatories:

- “When did the Defendant take possession of the rental unit?”

- “Did the Defendant ever fail to make a rent payment on time?”

- “Please list any conditions of the rental unit that violate local, state, and federal law.”

A tenant will want to pay close attention to exactly what is being asked in the interrogatory. They do not need to provide information that is not being asked. Additionally, a tenant may consider objecting to interrogatories (see “Objections to Discovery Requests” section below). If a tenant does not know the answer to the interrogatory, they may state “Defendant has insufficient information with which to respond to request number [number].”

- Requests for Production – an attempt to look at what documents or other physical evidence the other side has to prove its case. Code of Civil Procedure 2031.010 to 2031.510. Five-day deadline is in CCP 2031.260.

Here are examples of requests for production:

- “Provide all photographs in your possession of the water damage in the unit.”

- “Provide any notices in your possession that were sent to you by your landlord.”

- Requests for Admission – an attempt to have a fact admitted as being true, so it doesn’t have to be proved it at trial. Generally, either side may only serve 35 requests to admit on the other side, not including requests to admit copies of documents as genuine copies. Code of Civil Procedure 2033.030(b).

Here is an example:

- “Admit that Defendant resides at 123 Main Street, Salinas, California 93905.”

- If the tenant “admits” this is true in response to the request to admit, the tenant cannot contest, or argue that it’s not true, at trial.

- Say the tenant actually lives at 123 ½ Main Street (a small house behind the main house) and it is an illegal unit. At trial, the tenant would be unable to ask the judge to consider whether 123 ½ Main Street is an illegal unit because according to the tenant’s previously submitted admission, the tenant resides as 123 Main Street, not 123 ½ Main Street.

- If the tenant “admits” this is true in response to the request to admit, the tenant cannot contest, or argue that it’s not true, at trial.

In a tenant’s responses to the Requests to Admit, they only need to “admit” to statements that are 100% true, and “deny” statements that are untrue. Request for Admissions can be dangerous, because if the tenant does not timely respond to them, the landlord can ask the court to rule that the tenant admits everything (ask the judge to “deem the Requests admitted”) and then use those admissions at trial against the tenant.

- “Admit that Defendant resides at 123 Main Street, Salinas, California 93905.”

- Depositions – in person interviews about the facts of a case. Either side can request a deposition from the other side. Any person being deposed (deponent) will be required to swear to tell the truth during the deposition. The deponent may need to look at exhibits to answer questions.

A tenant being deposed only has to answer the question that they are being asked and nothing more. Also, if a tenant does not understand the question, a tenant can ask for a question to be repeated or rephrased, rather than assuming they know what the landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking. A tenant may also object to questions, and request bathroom or water/food breaks.

Attorneys usually conduct the depositions in their offices. The party requesting the deposition must pay for an interpreter if the deponent requires one. There is usually a court reporter present, who will record the interview and make a transcript of the interview available for purchase. The court reporter will ask the party being deposed if they would like to waive their signature on the transcript. Signing the deposition transcript indicates that the written words were the words they stated during the deposition. Generally, tenants should not waive their signatures. A tenant can obtain a copy of the deposition to read, review, and correct, if needed, before they provide a signature – indicating that those were the words they stated in the deposition.

Depositions may be scheduled for a date at least five days after service of the deposition notice, but depositions must happen five days before trial. Code of Civil Procedure 2025.270.

- Subpoenas – Subpoenas are a party’s way of asking for documents, information, or an interview of someone who is not a party to the lawsuit.

Reasonable accommodations:

If a tenant requires an accommodation for their deposition, they may submit the request to the landlord/landlord’s attorney in writing and/or call the landlord/landlord’s attorney to discuss the reasonable accommodation. Remember, individuals with disabilities do not need to disclose their diagnosis(es) to request an accommodation.

Objections to Discovery Requests

A tenant can object to discovery requests if they have a legal basis. Below are examples of different types of common objections. However, it should be noted that after an objection, a tenant may still have to answer the request based on their knowledge or, if it is the case, they can state that they don’t have sufficient information to answer the request.

Six common discovery objections are:

- Relevance: the landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking for information that is not related to the lawsuit.

- Relevance/privacy: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking questions that relate to personal identifying information, or private information.

- Overbroad and unduly burdensome: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking for way too much information that would be very hard to produce.

- Speculation: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is trying to get the tenant to say something outside their knowledge or outside what they have experienced.

- Compound question: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking the tenant a question that has multiple parts that requires separate answers.

- Asked and answered: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking the tenant the same question they already answered.

Each of these six common discovery objections listed above are explained in more detail below, with examples.

- Relevance: the landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking for information that is not related to the lawsuit. For example, in an interrogatory, the landlord asks the tenant what their boss’s name is, and their boss has nothing to do with their housing. A tenant’s sample response could be: “Defendant objects to Interrogatory number 9 as it requests information that is not relevant to these proceedings. Subject to said objection, my boss is Crystal Garcia.”

- Relevance / privacy: a landlord is asking questions that relate to personal identifying information, such as the tenant’s social security number, date of birth, driver’s license number, or private information such as their immigration status or specific disability or medical information. The tenant can object based on: (1) relevance, because the information is not relevant to the unlawful detainer, and (2) privacy because it is the tenant’s personal protected information. For example in a deposition, the landlord’s attorney asks the tenant for their social security number. Their sample response could be: “I object to that question on the basis of relevance and privacy.” A tenant does not need to answer the question with their personal private information.

- Overbroad and unduly burdensome: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking for way too much information that would be very hard to produce. For example, in a request for production, a landlord is requesting every doctor’s note the tenant has ever received regarding their disability they’ve had for 30 years. The tenant’s sample response could be: “Defendant objects to Production Request number 9 as overbroad and unduly burdensome and irrelevant, as it requests information from thirty years ago and my lease began only 8 months ago. Subject to such objections, Defendant provides the last two doctor’s notes she has most recently received and withholds the remaining documents.”

- Speculation: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is trying to get the tenant to say something outside their knowledge or outside what they have experienced. For example, in a deposition, a landlord’s attorney asks the tenant what they would have done if their landlord had answered their call even though their landlord didn’t answer their call. The tenant’s sample response could be: “Objection, calls for speculation. Subject to such objection, I would have told my landlord about the leaking faucet and asked him to repair it.” NOTE: In court, a tenant should never have to answer a question that calls for speculation. At a deposition, however, there isn’t a judge present, so a tenant can object and say speculation and not answer the question. Or the tenant can object and say something that does not hurt their case.

- Compound question: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking the tenant a question that has multiple parts that requires separate answers. For example, in a request to admit, the landlord’s attorney says: “Defendant admits that she played loud music at midnight on March 9, 2020 and April 3, 2020 because she was having parties on the premises.” The tenant’s sample response could be: “Objection, Request number 9 is a compound question. Subject to such objection, denied.”

- Asked and answered: a landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking the tenant the same question they already answered. For example, at a deposition, the landlord’s attorney asks “So you didn’t pay November’s rent right?” and the tenant answers, and then later the attorney asks “did you pay November’s rent?” The tenant can object to the second question by saying “objection, asked and answered” and does not have to answer the second question again.

NOTE: if a tenant has difficulty remembering the name of an objection during a deposition, they may still state “objection” and the reason for the objection in their own words. The judge may consider this.

5. A. Trial - Introduction

This section explains what happens next after the discovery process has ended – the beginning of trial. It goes over the basics of what to expect, how a tenant can prepare before trial, including what to bring to trial, and how to check into court.

Bench Trial or Jury Trial?

Tenants who end up going to trial, rather than settling the case through a settlement agreement, have the option of having their case decided by a jury, which is a group of people from the public who decide the case, or by a judge. A trial with a jury, is called a jury trial, and tenants who want this have to request it in advance (see Section 2. “Responding to the Summons and Complaint – the Answer and other Court Forms” and “Demanding a Jury Trial”). A trial decided by the judge and without a jury is called a bench trial. There are both advantages and disadvantages to jury trials and bench trials. If a tenant isn’t sure of which one to pursue, they can consult with an eviction attorney.

CAUTION: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some courts are only holding trials remotely. The court may be having trials by telephone, over a computer program, or by the “Zoom” platform, which may be accessed through a computer, phone, or other device with internet access or through phone service access. Tenants can call the clerk of their local court, or the local court’s self-help desk to get more information on their court’s remote hearing procedures.

To-Do’s Before Trial

Before trial, tenants may need to:

- Serve a witness list on their landlord and provide a copy to the court. The witness list contains the names and contact information of the people the tenant intends to have testify, or speak before the court, under oath, and on their behalf at trial. This list may include the landlord or the landlord’s witnesses if the tenant needs them to testify to prove a point. Tenants don’t have to call everyone on their witness list to testify, but they cannot have people testify that are not on the witness list.

- Serve jury instructions and a verdict form on their landlord/landlord’s attorney and submit a copy to the court. Tenants should call their local self-help center or legal aid agency and follow their local court’s procedures. There may be a “standing order” available with their judge’s instructions. For example – some counties with online remote trials are requiring that trial exhibits be placed in a drop box at the courthouse or emailed to the courthouse, along with being emailed or dropped off to the landlord/landlord’s attorney.

Before trial, tenants may want to:

- Think through the arguments they plan to make, and what documents, or witnesses they need to help prove this. It may be helpful to look at the answer form to see what defenses they claimed. Some tenants find it helpful to write out a basic outline that they bring with them to trial so that they do not forget the main points they want to make. The outline can include what their argument is, and, for each point of their argument - what pieces of evidence or statements from themselves or witnesses they will be using to prove it. See “Evidence” and “Witnesses” under “What to Bring to Trial” Section below for more information.

- Think through the arguments they think the landlord may make, and what documents or witnesses they may need to help disprove this. It may be helpful to look at the complaint from the landlord to see why they are claiming the tenant should be evicted. Tenants may find this helpful because then they can feel a little more comfortable about what to expect, and can be prepared to respond. For example, if they know their landlord is going to claim something that isn’t true, if they have it, the tenant can be prepared with evidence that proves it is false.

- Determine whether they will be needing an interpreter or reasonable accommodation to participate in the court process. See Section “Courtroom Basics” below for more information.

- Determine whether they will need to coordinate child care and/or transportation and/or time off work to be able to attend court. See Section “Courtroom Basics” below for more information.

Courtroom Basics

Time: Tenants need to arrive early to court. Tenants need enough time to arrive, go through metal detectors, find their courtrooms, find their cases on the “call sheets,” and check in with the clerk before the judge or clerk starts calling cases at the time listed for their court dates. A call sheet is a piece of paper taped to the courtroom door or pinned on the wall next to the courtroom door stating all the case names and case numbers that have court dates that day.

Remote Trials: If the trial is remote instead of in person, tenants still want to be sure that they have given themselves enough time to get ready before court starts. For instance, tenants may need to set up the space where they are going to access the hearing, whether it is from their phone or a computer, and to test any technology they will be using, including their internet connection, if necessary. To the best of their ability, tenants should try to ensure the space they will be using is quiet and private.

Dress: Tenants should try to dress neatly.

Child care: There may not be child care available at the court house. Everyone watching court has to be quiet when the judge is on the bench or the bailiff, which is like a security guard in the courtroom, will ask them to leave the courtroom. The same is true for remote hearings – the judges will not want to be distracted by any background noise on the call, including children.

Interpreter: Before the court date, tenants can call the local courthouse to request an interpreter. On the day of their hearing, tenants can let the court clerk know they need an interpreter as soon as they can, or when they enter the courtroom. If the judge calls the case and the interpreter is not there, tenants can ask the judge to wait for the interpreter to arrive.

Reasonable accommodations in court: Please see Section 7 entitled, “Reasonable Accommodations in Court”

What to Bring to Trial

Tenants should have all of their evidence with them and organized, and have their witnesses present in court at the time of their court hearing.

Evidence – For all pieces of evidence, tenants need to bring at least 1 original and 2 copies. This is because the landlord has a right to see the original and will receive one copy. The judge will receive the original and the tenant can use one copy during the trial. If the trial is taking place remotely, the tenant can check with the court clerk before the trial date to find out how documents will be reviewed during trial.

Some examples of evidence tenants can bring to court are:

- Photographs of the defects or poor conditions in their apartment;

- Certified copies of any health department reports, government records, or business records;

- All rent receipts or proof of payment of rent; for example, bank statements showing cashed checks, money order stubs, or receipts; and

- Any letters, notices, text messages, or voicemail communications that tenants had with their landlord. For example, tenants can bring any letters they had given their landlord asking for repairs or informing their landlord of any problems with the apartment. Tenants can also include envelopes, because the postage stamps show the date of mailing and the envelopes show who the letter was mailed to and from.

CAUTION: Tenants cannot postpone trial because they don’t have all their evidence with them (or submitted correctly for internet trials). Tenants must be ready on their trial dates.

Witnesses – Witnesses must be present in court at the start of trial, and available to answer questions and testify. For example, a tenant cannot bring a letter from their neighbor instead of having their neighbor come to court to testify. This is because a letter cannot be cross-examined by the other side. If tenants are concerned that their witnesses may not come to court, tenants may issue subpoenas. Tenants can obtain subpoenas from the court clerk’s office and then have someone else serve the subpoenas on their witnesses before trial.

If witnesses ask, tenants may have to pay the witnesses’ mileage and witness fee. ($35/day plus mileage actually traveled. Gov. Code 68093.) Tenants don’t have to pay for their landlord’s mileage or their landlord’s witness fee if they call their landlord or their landlord’s witness as their own witness.

Checking Into and Speaking in Court – Courtroom Culture

- There may be a call sheet posted on the courtroom door or on the wall next to the door. Tenants should look for their case number or name and remember what number it is on the call sheet list.

- Next, the tenant will go inside the door and get in line to tell the court clerk that they are present, what their court call number is, and that they are the Defendant. At this time, tenants also confirm with the clerk that an interpreter is available if the tenant needs one. If applicable, the tenant can also confirm with the clerk that the court is aware of the tenant’s reasonable accommodation request filed with the court.

- After checking in, tenants should have a seat and make sure their cell phones are either off or on silent. If tenants are very early and would like, they can ask their landlord or landlord’s attorney to talk in the hallway outside the courtroom to attempt to settle their case. (See Section 3 entitled “Settlements and Mediation”) However, tenants should make sure they are in the courtroom when the judge is “on the bench.” (The “bench” is the desk in the front of the courtroom where the judge sits; “on the bench” means when the judge sitting at the desk).

- When the judge comes into the courtroom, everyone in the courtroom that is able to stands up. When the judge sits, everyone sits. When the judge is on the bench, the only people who should be talking are the judge, the parties that have been called in front of the judge, and the court clerk.

- When the tenant’s case is called, the tenant stands up if able to, and states their last name loudly or states “Defendant”. Then the tenant goes up to the bench and stands, if they are able to, in front of the sign that says Defendant.

- If the tenant needs an interpreter and one isn’t present, the tenant can ask the judge for an interpreter.

- If the tenant still hasn’t had a chance to speak with their landlord about trying to settle the case and would like this chance, the tenant can ask the judge to allow them a few minutes to speak with the landlord and the landlord’s attorney regarding the lawsuit. Then the tenant and the landlord/landlord’s attorney go into the hallway or a separate room, if available, and speak with each other. Once the parties have finished talking, they’ll go back inside and check back in with the court clerk to have their case called before the judge again.

NOTE: Appropriate names to call the judge are “Judge” and “Your Honor.” When the parties are in front of the judge, the parties are supposed to be talking to the judge and not to each other. If tenants are able to, they should look at the judge and talk to the judge when they speak, and not talk to the landlord/landlord’s attorney. For example, you’re at the bench and the landlord’s attorney tells the judge that you agreed to move out. Instead of saying “no I didn’t, what are you talking about” to the attorney, you would say something like this to the judge: “Judge the attorney for the landlord is saying something I did not say. What I did say was that I might be willing to move out if they gave me more time, but we have not had the chance to discuss this yet. Can I have the opportunity to discuss this with my landlord and their attorney in the hallway?”

5.B. Trial – Step by Step

This section will provide a general step-by-step flow of how both the tenant and the landlord tell their sides of the story, and how to present evidence during the trial, including witnesses.

Who’s Who and What Happens When?

Eviction trials can go quickly. The landlord (Plaintiff) will present their entire case first. After this, the tenant (Defendant) presents their entire case. Both parties have the opportunity to go through the same steps to try and prove their case. These steps are:

- Opening Statement – brief summary of the party’s argument for why they should win the case (landlord or tenant) and what they intend to prove or disprove at trial.

- Witness Testimony – an opportunity for a party to bring people to speak in court, called witnesses, to speak about the information they know, or to confirm photographs or other documents.

- Cross-Examination – asking questions of the other side’s witnesses (for example, a tenant questioning a witness the landlord brought to speak).

- Re-direct Examination – time to question a party’s own witness after the other side cross-examines their witness.

- Present Evidence – an opportunity to present documentary evidence.

- Closing Arguments – an opportunity for both parties to provide a summary of their argument, about what the evidence during the trial proved, and why the judge or jury should agree with them.

Each step is explained in more detail below for both the landlord and the tenant, including examples and helpful tips. Note: Some judges will not allow opening statements and/or closing arguments in evictions. But if one side gets a chance to do an opening statement, for example, the other side must be given a chance to do an opening statement – a party may still decide to “waive” or not do the opening statement, but they must be offered the opportunity to give one.

Part 1 - The Landlord’s Case

During the eviction trial, the landlord will have the first opportunity to present their case – or prove why the tenant should be evicted. To make their case, the landlord or landlord’s attorney may call witnesses and/or present evidence. During the landlord’s case, tenants should listen carefully and/or take notes of anything the landlord/ attorney presents that is not true or not the whole truth. This will help them prepare for cross-examination and to make objections. Cross-examination and objections are discussed below in number four.

- Opening Statement: The landlord will begin their case by presenting a basic summary of why the tenant should be evicted.

- Witnesses: The landlord will call witnesses and ask questions that they think will help prove why the tenant should be evicted. The landlord/landlord’s attorney may even call the tenant to testify to help prove their case. During the landlord/landlord’s attorney’s presentation of their witnesses, the tenant may object to things that are said, if they have a legal basis for the objection. If the judge says “overruled,” the witness may answer the question. If the judge says “sustained,” the witness cannot answer the question. (See below more information on making objections during trial and, for additional objection examples, see “Objections to Discovery Requests” in Section 4.)

- Objections: Except for making objections, the judge will not like it and may scold tenants if they interrupt the other side or talk while the other side is presenting their case. Typical trial objections are “relevance” (the questions being asked are not related to the case), or “hearsay” (the witness is repeating what someone else said outside of court to prove what that person said is what actually happened). An example of a hearsay statement by a landlord would be: “the tenant’s neighbor told me on several occasions that the tenant was being loud at nighttime” when the neighbor is not present as a witness in court.

Here is an example of how a tenant can make an objection during a witness’s testimony: A landlord’s attorney asks the landlord’s witness why the tenant did something. The tenant calls out loudly “objection, calls for speculation,” right after the landlord asks the question and waits for the judge to “rule” (decide if they agree or disagree with the objection). In this case, the judge would say “sustained,” which means the landlord’s witness cannot answer the question because the tenant made a valid objection.

- Cross Examination: Right after the landlord/landlord’s attorney finishes asking the witness questions, the tenant will be given a chance to ask the same witness questions. This is called cross-examination. The point of cross examination is to either highlight something the witness said that can help the tenant’s case, or try to lessen the harm of something they said that would hurt the tenant’s case.

It is helpful if tenants take notes of what the witness says when the landlord/landlord’s attorney is asking questions, and write down any points the tenant would like the witness to clarify or answer. That way, when it’s the tenant’s turn to ask questions on cross-examination, they are prepared.

NOTE: cross-examiners are not supposed to ask witnesses about new subjects, instead, they are only supposed to ask witnesses about subjects that were discussed during direct examination. This means that if the landlord/landlord’s attorney’s witness wasn’t asked about a subject that would be helpful for the tenant, the tenant will have to wait to ask about that subject until it’s the tenant’s turn to present the tenant’s case. Then, they can call this person as their own witness, and ask the witness about that subject.

Example: The landlord asked the witness only about payment of rent, but not about the tenant’s poor apartment conditions on direct examination. During the tenant’s cross-examination, they can ask questions relating to payments. Later, when it’s the tenant’s turn to present their case, the tenant can call this person as their own witness to ask them about the poor conditions in the tenant’s apartment.

- Re-Direct Examination: After the tenant finishes cross-examination of the witness, the landlord’s attorney may do a “re-direct examination” (meaning, question the same witness one last time about the witness’s answers during the cross-examination). Then the judge will excuse the witness and the landlord’s attorney may continue presenting other evidence and calling other witnesses for the landlord.

- Present Evidence: During their turn to present their case, the landlord/landlord’s attorney may also present documentary evidence as exhibits that they think will help prove why the tenant should be evicted. Examples of exhibits can be photos or bounced check fees.

When presenting evidence to the court, the landlord/landlord’s attorney needs to do a few things to make sure that the evidence is “entered into the record.” If the evidence isn’t properly “entered,” then the judge or jury cannot consider it when making its final decision.

First, the tenant is allowed to see the original exhibits and must be given a copy of the exhibits. The landlord/landlord’s attorney will also need to have the landlord or other witnesses answer questions about the documentary evidence to prove where the document came from and that it is a true and correct copy. Tenants are allowed to object to the evidence being admitted based on “foundation” if the landlord/landlord’s attorney cannot show where the documents came from or that they are true and correct copies.

See “Part 2 – The Tenant’s Case” below for further information on entering evidence in court.

Part 2 – The Tenant’s Case:

To not lose the lawsuit, the tenant needs to show that the landlord:

- failed to prove its case or

- that the tenant has defenses that prevent the landlord from winning.

The steps in the tenant’s case follow in the same order and fashion as the steps in the landlord’s case.

NOTE: Motion for a Nonsuit. After the Plaintiff “rests,” or has presented all of the witnesses, and entered all of the evidence they want to enter to try and prove their case of why the tenant should be evicted, the tenant can ask the judge to dismiss the lawsuit by motioning for a nonsuit. Cal. Code of Civil Procedure §581c. For example, the tenant can say “Your Honor, I respectfully move for a nonsuit.” The judge will “grant” or agree with a nonsuit motion if the judge finds the landlord cannot prove their case based on the evidence heard so far. If this motion is granted, the tenant does not have to present their case because the lawsuit would be over. If the judge denies the motion for a nonsuit, the tenant still has the opportunity to present their case, which is called a defense.

- Opening Statement: The tenant will tell their side of the story to the judge or jury. Most people, including the judge and jury, find information easier to understand if it is told in chronological order, meaning the order that it happened. Tenants will only want to include details that are relevant to the story, and explain why those details matter. The judge may interrupt the tenant with questions. The tenant will need to answer the judge’s questions and then continue to tell their side of the story.

NOTE: tenants who may be nervous about forgetting something or getting off track if interrupted, may want to bring notes or an outline of what they want to say. That way, if the judge interrupts them with a question, they can look at their notes to pick up where they left off. - Witnesses: The tenant will have the opportunity to present their own witnesses, just as the landlord presented theirs. Tenants often find it helpful to write down their questions or points they want the witness to talk about in advance so they don’t have to remember everything in the moment.

The tenant will call each of their witnesses one at a time. The witnesses can only tell the judge things that are related to why the tenant is being evicted. The witnesses can also only testify to things they personally saw, heard, smelled, or felt. The witnesses will not be able to start speaking on their own. Instead, the tenant will have to ask their witnesses questions to get them to share information. The judge will not question the tenant’s witnesses for the tenant. However, the judge may have a few questions for the witnesses either during the tenant’s questioning or after the tenant finishes questioning the witness. A tenant will also enter any evidence that they want through their witnesses while their witness is testifying. (See section below entitled “Entering Evidence into the Record.”)

It is often helpful for the judge and/or jury to understand who the witness is, how they are connected to the person that called them as a witness, and how they know what they know. This is called, “laying the foundation”. Here is a sample set of questions that provides an example of how to lay the foundation for the information the tenant is trying to get the witness to share:- What is your name?

- How are you related to apartment 9 at 123 Street?

- Have you been inside the unit before?

- Was there a bathroom?

- Did you use the bathroom?

- Were there any problems with the bathroom when you attempted to use it?

- Please describe the problems.

As shown in this example, to have a neighbor testify about the conditions of the bathroom, the judge or jury will first want to hear who the witness is, and how they came to know what they know about the bathroom. This helps the judge or jury decide how believable the witness and the information they have provided is.

During the tenant’s presentation of their witnesses, the landlord/landlord’s attorney may object to the tenant’s questions. When this happens, the tenant waits for the judge to rule on the objection before continuing. If the judge says “overruled,” the witness may answer the question. If the judge says “sustained,” the witness cannot answer the question. The judge will likely allow the tenant to ask the question another way (“rephrase” the question).

A common objection is hearsay. The following statement is an example of hearsay: “The plumber told me my apartment was uninhabitable.” To avoid a hearsay problem, the tenant could call the plumber as a witness and have the plumber explain why the plumbing conditions made the tenant’s apartment uninhabitable. The landlord/landlord’s attorney would then have the opportunity to cross-examine the plumber.

- Cross-Examination: After the tenant finishes asking their questions of each witness, the landlord/landlord’s attorney will have a chance to cross-examine the tenant’s witnesses. The landlord/landlord’s attorney is only allowed to ask questions about the same subjects the tenant asked questions about. If the landlord/landlord’s attorney asks about a different subject, the tenant can object to the question as “outside the scope.”

- Re-Direction Examination: After the cross-examination by the landlord/landlord’s attorney, the tenant can ask follow-up questions of their witness. This is called “re-direct” examination. The tenant has to limit their questions to the subject that the landlord was just asking about on cross-examination. For example, if the landlord/landlord’s attorney cut off the tenant’s witness mid-statement, or the tenant knows their witness could say something helpful about the subject, the tenant can ask that question on re-direct.

- Entering Evidence into the Record: There’s a way the parties have to present evidence to make sure the evidence they have brought to trial can be considered by the judge or jury. The following section provides examples of how tenants can enter evidence.

EXAMPLE 1

The tenant did not pay the rent because the landlord would not fix the problems in their apartment:

- The tenant makes 3 copies of each photograph and document they want to use. On the back of each photo or on the front of the document’s first page, the tenant writes Defendant’s Exhibit A (all 3 copies will say Exhibit A). On the next photo or document, the tenant writes Defendant’s Exhibit B (on all 3 copies). On the next photo or document, the tenant writes Defendant’s Exhibit C (on all 3 copies), and so on.

- The tenant tells the judge: “I did not pay the rent because of the bad conditions and the landlord would not make repairs.”

- The tenant gives copies of the photos or documents to the landlord/landlord’s attorney, and then gives copies of the photos or documents to the judge.

- The tenant goes through the photographs one at a time with the judge and tells the judge the following information about each picture:

- The tenant states the photo is a fair and accurate depiction of the conditions at the time the photograph was taken and/or as the conditions are now, and that the tenant is familiar with what is shown in the photograph. (Though it is not required to enter the photograph into evidence, the tenant is prepared to answer who took the photograph and when it was taken.)

- The tenant states what exactly is shown in the photograph. For example, the tenant says, “when you turn on the water, the water leaks underneath the sink and you have to catch the water in a bucket so it doesn’t spread all over. You can see my yellow bucket under the sink.”

- The tenant states how long the problem has existed. The tenant is specific. The tenant includes any evidence they have about when this may have started, such as health inspector reports.

- The tenant states when they told the manager/landlord about the problem. The tenant includes relevant facts, like how often they told the landlord about it. Again here, the tenant is specific – for example, instead of answering “all of the time,” the tenant says “every other day for an entire month” or “on November 9, 2020 I called Mr. Notagood Landlord and left a voicemail, telling him about the leak in the voicemail. On November 10, 2020 I texted Mr. Landlord and asked for help with the leak. On November 11, 2020 I emailed Mr. Landlord and asked for help with the leak. And on November 12, 2020, I mailed Mr. Landlord this letter, marked as Defendant’s exhibit 4. You can see my receipt from the post office, dated November 12, 2020, which is additional proof of my mailing the letter. This receipt is marked as Defendant’s exhibit 5.”

- The tenant asks the judge to have the photographs “entered into evidence.”

- The tenant states whether or not the landlord repaired the problem. For example, the tenant tells the judge if the landlord promised to fix the problem, but then never did.

- If the tenant or the tenant’s family or friends did not cause the problem, the tenant tells the judge, and includes relevant information. For example, if there are cockroaches, the tenant would say, “My family and I don’t leave food out. We take out our garbage when it’s full and we store the garbage can in a cabinet so it is not out in the open. We also wash our dishes after each meal and don’t leave dishes in the sink overnight.”

- The tenant tells the judge how the problem affects the tenant and their family. For example, for a leak the tenant would say, “because of the sink leaking, it’s very stressful to wash the dishes. We have to keep going out to the yard to dump the bucket and we have to scrape off our food and carry our dishes to the bathtub to wash. Then we have to clean the bathtub more frequently.” Or, for cockroaches, the tenant would say for example: “I am worried that the cockroaches will spread disease. I have a baby that needs to crawl on the floor and has toys on the ground and I don’t want her touching where the cockroaches have been.”

- For all other evidence like health reports, letters the tenant gave to the landlord, etc., the tenant will first give copies to the landlord/landlord’s attorney, and then give copies to the judge. Again, the tenant will explain to the judge what the documents are and what the documents help the tenant to prove. After this background explanation, the tenant will ask to have the documents “entered into evidence.”

EXAMPLE 2

If the landlord filed suit because she gave the tenant a three-day notice on the 3rd of the month, but the tenant tried to pay rent on the 8th of the month when the tenant usually pays the rent:

- The tenant tells the judge “I usually pay my rent on the 8th of the month and the landlord accepts it.”

- The tenant shows the landlord/landlord’s attorney and then the judge all of their rent receipts that prove that they have always or usually paid their rent on the 8th of the month, not on the 1st of the month.

- The tenant has a chart ready showing what days they paid the rent for the last year or more and tells the judge that each one of the payments and dates on the chart represent the times and dates on which they paid rent.

- The tenant asks to enter the receipts and the chart into evidence.

NOTE: The landlord/landlord’s attorney will be able to ask witnesses or the tenant questions in cross-examination regarding the document.

Part 3 – Closing Arguments

After both the landlord and the tenant have presented their entire cases and defenses, the judge may allow both parties to make a “closing argument” or a final statement. In this statement, tenants tell the judge or jury the reasons why the judge or jury should agree with them and not agree with the landlord. A tenant can also use this time to clarify for the judge or jury what the evidence they heard meant, and why it is important to their defense. Tenants state (1) the facts why the landlord cannot prove the landlord’s claim against them and (2) the facts that support their defenses. Tenants then ask the judge or jury to dismiss the case.

6. The Final Decision and What Happens Next

This section will explain how both parties find out who won the eviction case, and what happens after a final decision has been made.

Statement of Decision

After closing arguments are given, tenants can ask the judge for a “Statement of Decision.” The Statement of Decision will explain the reasons why the tenant has won or lost. Judges are usually not required to give a written decision in a short trial lasting fewer than a day or 8 hours. Tenants must ask the judge for a Statement of Decision before the judge rules (meaning, before the judge states their decision).

“Judgment” or “Order

The judge or jury will usually decide on the case while the tenant is still in court. If not, the tenant will be notified by mail, usually within a few days after trial. The court’s written decision, or “order” will include four items:

- A statement that will say the tenant is allowed to stay in their unit (if the tenant won) OR that the tenant must move out (tenant lost);

- Whether or not the tenant has to pay back rent;

- Whether the side who won can get money from the losing side for court costs. (If the tenant won and wants the other side to pay their costs, they may recover cost by filing a form within 10 days after trial. The form is available here: https://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/mc010.pdf); and

- Whether the losing side has to pay for the winning side’s attorney’s fees. This could happen if there is a written lease agreement between the landlord and the tenant allowing such fees and the winning party hired an attorney. Tenants do not get attorney’s fees if they represent themselves.

CAUTION: Tenants must read the order carefully because even if they “win” on trial day, the court may still order them to take other actions to avoid eviction. For example, the order may require the tenant to pay back rent by a certain date and if they don’t, the tenant can still be evicted even if they “won” their case. If tenants with disabilities do not understand what their order says, they can call DRC for help in understanding what it means.

Win or Lose What’s Next?

Example of “winning” at trial:

- The judge says the tenant is allowed to stay in their unit because they proved their defense of the breach of the warranty of habitability, but the judge ordered them to pay a portion of the back rent within 5 days.

- If a tenant pays the back rent on time (and gets a receipt), the tenant will win the case and won’t have to move out.

- If the tenant doesn’t pay the back rent on time, the landlord will win and the tenant will have to move out. (See “Notice to Vacate” section below.)

Example of “losing” at trial:

If the tenant “loses” at trial, the landlord will receive a “judgment of possession,” which gives possession of the unit to their landlord. Tenants in this situation have a few options:

- They can ask for more time.

- If the judge tells the tenant in the courtroom that they will be “evicted” or have to move out, tenants can ask the judge right then and there for more time before they have to move out. To do this a tenant can say: “Your Honor, I request 30 days to move.” This extension of the time to move out is called a “stay of execution” of the court order. (See end of Section 3, entitled “Settlements and Mediation”)

- Tenants should be ready to explain why they need more time to move. NOTE: A tenant might have to pay their landlord for this extra time in their unit.

- Even if the judge does not give the tenant more time, the tenant does NOT need to move out the same day as their trial. (See the below regarding the notice to vacate.)

- Tenants can ask for “relief from forfeiture,” if appropriate. (See end of Section 3, entitled, “Settlements and Mediation”)

- Tenants can ask for a sealed court record, so that the eviction does not appear on their credit record.

Notice to Vacate

The notice to vacate is a white paper with red lettering that says the tenant has five days to move out and states the date by which the tenant has to move out. Tenants won’t get a notice to vacate until after they lose their case. The sheriff will tape a copy of this notice to the tenant’s unit door.

After the sheriff posts the notice to vacate on the tenant’s door, the tenant is on notice that the tenant will have to move when the sheriff says the tenant has to move.

If tenants need to ask for a few more days in their unit and their landlord agrees, tenants need to get this permission in writing, keep this permission ready to show the sheriff, and make sure the landlord informs the sheriff. Tenants may also call the sheriff to verify their landlord informed the sheriff.

When the sheriff comes, the sheriff will only give the tenant a couple minutes to leave the unit, so tenants will not have enough time to move furniture or other belongings. It will likely not matter if they have children, have disabilities, or are sick. They will have to leave their unit immediately.

If the tenant’s belongings are not out of their unit before the sheriff comes, their landlord will likely store their belongings and the tenant will have to pay money to get them back. If the tenant did not remove their belongings before the sheriff locked them out, and wants to prevent their items being thrown away, the tenant can write a letter to the landlord within 18 days of being locked out. The tenant should date the letter on the date the tenant writes the letter, keep a copy of the letter for themselves, mail the letter to the landlord via certified mail, or hand-deliver the letter and require in the letter that the landlord to sign the tenant’s copy acknowledging their receipt.

Here is a sample letter:

(Date)

Dear (Manager/Landlord’s name):

I was not able to take all my things with me before I had to move out. [List or description of belongings left behind.] Please do not throw any of my things away. I will contact you soon to set up a time to get my things.

Thank you,

(Your name)

(Address)

However, tenants may still have to pay their landlord to get their belongings back. The landlord cannot charge more than a “reasonable moving fee,” AND the unit’s daily rent for each day the landlord stores their belongings. Tenants will need to give the landlord an address where they receive mail for the landlord to send a demand for the fees.

CAUTION: if a tenant does not give a letter to the manager/landlord, the manager/landlord may claim the tenant abandoned their property.

7. Reasonable Accommodations in Court

What is a reasonable accommodation in court?

A reasonable accommodation is a change in a practice, policy, or procedure that allows a person with a disability to enjoy equal access to their legal proceedings in court.

Why might tenants need to request a reasonable accommodation?

A tenant may need to request a reasonable accommodation because one of their disabilities may prevent them from being able to testify in court, appear in their case in court, or participate in their court proceedings in other ways.

For example, a tenant with a disability may need to eat while in the courtroom, or, a person with a cognitive impairment may need a support person to assist them with communications with court personnel. Other people with disabilities may need the court to provide assistive listening devices or readers, or may need the court to reassign a hearing to a courthouse that is more accessible.