California Memorial Project (CMP)

California Memorial Project (CMP)

Disability Rights California’s Peer Self-Advocacy (PSA) Program advocates for and oversees the California Memorial Project (CMP). The CMP’s mission is to honor and restore dignity to individuals with mental health and developmental disabilities who lived and died in California state institutions.

California Memorial Project: Giving Recognition to our Peers – Past and Present

Disability Rights California’s Peer Self-Advocacy (PSA) Program advocates for and oversees the California Memorial Project (CMP). Started in 2002, the CMP is dedicated to a profound yet often overlooked mission: honoring and restoring dignity to individuals with mental health, intellectual and/or developmental disabilities who lived and died in California’s state hospitals and developmental centers.

Life in an Institution

In the past, individuals were taken from the community and committed to locked institutions for a variety of reasons – some may have experienced significant personal losses, such as poverty, poor health, trauma, displacement, or the loss of loved ones. Others may have had physical limitations or experienced unusual thoughts or beliefs that others didn’t understand. Many of them had career or artistic aspirations or plans to start a family but died at the institution without the opportunity to realize their goals.

Doctors diagnosed them with a psychiatric, intellectual and/or developmental disability they believed required hospitalization. But not enough research and knowledge was available at the time to determine the most effective treatments for people with these disabilities. Many were prescribed medications or subjected to treatment methods that might have contributed to their deaths.

As a result, some did not receive the treatment they needed and remained at these institutions for several years or even for the remainder of their lives. Failed by the medical institutions that were meant to help them, they were isolated from their families, friends and communities, essentially dismissed and forgotten by society.

Locked away in these institutions, they were stripped of their rights and forced to receive treatment against their will. Without the freedom to make their own decisions, many languished, lost hope and passed away before they could return to the community.

It is estimated that more than 45,000 individuals died while residents in state institutions from the mid-1800’s to the 1960’s. When people died, they were often buried in mass or unmarked graves, with only a number on a stone or wooden stake - their identities erased, as if they never existed. These individuals, our peers, never received the respect or recognition they deserved, in life or in death.

CMP History

Peer advocates worked together for laws to bring back dignity to our peers. Having lived in institutions themselves, many of them had experienced firsthand the disrespect, mistreatment and neglect. The California Memorial Project (CMP) was born out of the desire to rectify these injustices. Created through a collaboration of 3 peer advocacy organizations: Disability Rights California’s (DRC) Peer Self-Advocacy Program, The California Network of Mental Health Clients and People First of California, our goal was and still is to end the lack of care and disregard toward our peers.

Working closely with then-Senator Wesley Chesbro, legislation was passed in 2002 (Senate Bill 1448) and 2006 (Senate Bill 258) that laid the groundwork for the project to identify the locations of gravesites, research patient records, and develop plans for the restoration of these long-forgotten cemeteries.

The CMP team identified the following additional goals:

- To hold annual California Memorial Project Remembrance Day Ceremonies throughout the state;

- To document the history of the Peer Movement;

- To place memorials where the people who lived and died in state institutions were buried;

- To collect the stories of our peers who themselves were placed in institutions and now live in the community to give voice to their personal experiences; and,

- To gather the stories of our peers who currently live in these institutions to reveal what life is like today in a locked facility.

These efforts ensure that individuals who died in state institutions are remembered with dignity, rather than relegated to the annals of forgotten history. We also give recognition and acknowledge those who live in these institutions today, so they are seen, heard and no longer silenced.

Remembrance Day Ceremonies

In the first year of our project, in 2002, the CMP held its first annual California Memorial Project Remembrance Day Ceremony. The Remembrance ceremonies take place throughout California – some on the grounds of state institutions and others at local cemetery gravesites where our peers were buried. In 2010, with Senator Chesbro’s support, the State Assembly declared the 3rd Monday of every September as California Memorial Project Remembrance Day.

On this day each year, the CMP also hosts a virtual Remembrance Day Ceremony for those who are unable to attend one of the in-person ceremonies. During the ceremonies, we provide a brief history of the CMP, invite peers to share their personal stories of hope and recovery, recite poems and display art created by current state hospital residents, and lead a statewide moment of silence to uplift and celebrate the lives of all our peers.

“My favorite part was listening to the stories of individuals formerly institutionalized and gaining a better understanding of the type of support they needed instead of seclusion they received,” said Paula Sandoval, DRC staff member, after attending her first Remembrance Day Ceremony

This year, the theme of the Remembrance Day Ceremony at Metropolitan State Hospital is: Let’s "Never Give Up: Better Tomorrows Will Come!" For the Patton State Hospital Remembrance Day Ceremony, the theme this year is: "Like the butterfly, the soul transforms—rising from its earthly shell into light and freedom, gently reminding us that love never dies, it only changes…”

The Remembrance Ceremonies are a yearly time to reflect on the lives of those who were lost and reaffirm the declaration that no one who was formerly or is currently institutionalized will be forgotten.

View the Event HereHistory of the Peer Movement

The CMP conducts research and documents the history and progress of the Peer Movement (also known as the mental health consumer/ex-patient/psychiatric survivors (c/x/s) movement). In the past, individuals in state institutions were stripped of their rights and separated from their families, friends, and communities. Many were forced to receive treatment against their will without the freedom to make their own decisions and choose what was right for them. This is still happening to our peers today.

Many of these institutions closed in the middle of the 20th century. Large numbers of people were discharged as a result of legislative efforts to return people to the community, but needed services and supports were not available.

People who returned to the community came together to form advocacy groups at the beginning of the civil rights movement. Led by and for people with psychiatric, intellectual, and developmental disabilities, this activism marked the birth of self-advocacy and self-help groups in California.

Evolving from its civil rights roots in the 1960s to the modern peer support workforce today, the movement is taking on a new generation of leaders and initiatives. Moving forward, the CMP will continue to gather information about the history and progress of the Peer Movement.

*The Peer Self-Advocacy Program sprang from the efforts of peer advocates with mental health disabilities in 1989 and continues providing peer self-advocacy services today.

Remembering Sally Zinman: Pioneer Peer Advocate and CMP Team Member

Sally Zinman, a pioneer Peer Advocate from the beginning of the Peer Movement in the 1970s, passed away on August 25th, 2022. Sally was a fierce and fearless advocate who never stopped fighting against the injustice of involuntary mental health treatment. She played an important role in the beginning phases of the CMP, and we will remember her for her 45 years of passion and dedication to our peer community.

Sally Zinman, a pioneer Peer Advocate from the beginning of the Peer Movement in the 1970s, passed away on August 25th, 2022. Sally was a fierce and fearless advocate who never stopped fighting against the injustice of involuntary mental health treatment. She played an important role in the beginning phases of the CMP, and we will remember her for her 45 years of passion and dedication to our peer community.

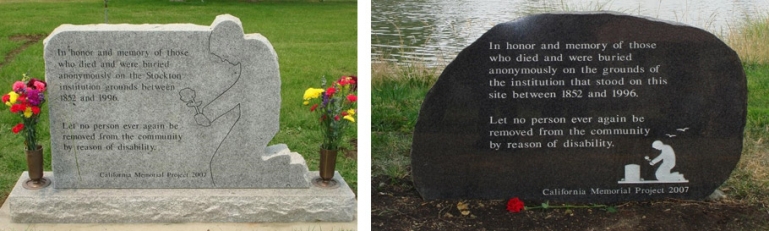

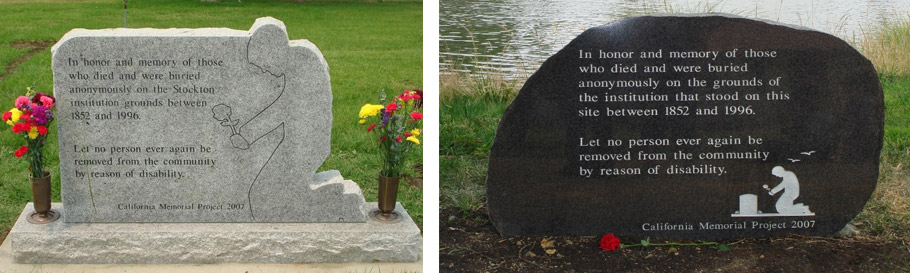

CMP Memorials

The CMP has placed numerous memorial plaques and monuments at sites where people from California state institutions were buried.

Some monuments state: "Let no person ever again be removed from the community by reason of disability... Let us honor their memory by reclaiming and healing our past... Let no person ever be laid to rest without recognition."

Recognizing the full names of those who died is another way the CMP aims to bring dignity and respect back to those who were buried without proper recognition. In 2022, a monument dedicated to the lives of over 8,000 people who died at Napa State Hospital was unveiled during Napa’s remembrance ceremony. The monument is the first of its kind to include the full names of those who died between 1876 and 1964 and were otherwise buried in unmarked graves.

The Napa memorial was a multi-decade effort that involved hand-reviewing former state hospital ledgers and decoding descriptions of those who were unnamed when they died. The monument serves as a model for future memorials at other former state insitution sites across California.

Some of the wording on the monuments read:

Some of the wording on the monuments read:

- “Let no person ever again be removed from the community by reason of disability..."

- “Let us honor their memory by reclaiming and healing our past...”

- “Let no person ever be laid to rest without recognition...”

- “Gone but not Forgotten”, “We Remember You”.

Gone, But no Longer Forgotten:

The California Memorial Project (Video)

Stories from our Peers - In Their Own Voice

The CMP brings awareness and appreciation for our peers who are with us today by speaking with current and former residents of state institutions to hear about their personal stories and experiences in their own voice. By preserving our stories, we reclaim and honor our past.

We spoke with a current resident at a state hospital in California who has lived most of his life in confinement. View their story here.

30+ Years in a Mental Institution

The California Memorial Project (CMP) was established in 2001 to honor our peers with mental health disabilities who lived and died in institutions. Since that time, we still house people involuntarily for years on end, they still die away from their loved ones, and they are still being held against their will for “treatment.”

The CMP continues to recognize our peers from the past. Now we are adding a new and valuable focus, to acknowledge residents who presently live in those same institutions for mental health “treatment.” We decided to talk with residents who have lived most of their adult lives inside a state hospital in honor of our peers who have gone before us.

Inside The Walls-Of-Treatment

Many people are still living in large, over-populated and locked settings simply because of their mental health. These state “hospitals” control every aspect of their day-to-day lives. Imagine not being given the chance to decide what you can and cannot do for every choice in your life. You do not have your own clothes, you cannot choose to have a cup of coffee or sit outside, you cannot even decide to change your hairstyle just because you want to.

We are talking about people - they are our loved ones, family and friends, neighbors, musicians, engineers, teachers, … they are our Peers - just people, like you and me. Some have lived in confinement for over 30 years, with no hope of ever leaving.

Most are men who have been accused of committing a crime. Many pled “Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity” (penal commitment code 1026.5) because of their mental health and the crisis they were in at that time. They are not receiving meaningful treatment for their conditions and have not been able to seek help outside the state hospital.

But no one wants to admit they probably won’t get out. They will probably die there. Most outsiders don’t know they live in confinement, not for crimes but for “treatment.”

Their Lives, Their Stories

We interviewed some residents and asked them to share their personal stories with us. We called the patient phones, but most of the time no one answered. When someone did, we asked for people by name, those peers with whom we had a connection. Some were in their rooms, often sleeping, or in the day room watching TV.

The patient phones hang on the walls in the middle of the unit halls. Although they have a “right” to confidential phone calls, anyone and everyone can hear what they’re saying. Loud voices, background conversations and people walking by make communication hard. But they are used to daily interruptions, whether it be early morning wake-up calls, treatment group meetings, standing in the medication line or structured “free time.”

While their day-to-day lives are similar, their experiences vary as they talk about “the good, the bad and the ugly” of living in a state hospital.

In His Own Words

Greg Roberts (name has been changed) has been at Patton State Hospital for the past 41 years. He is now 61 years old. When asked to describe a regular day in his life, he immediately told me, “I don’t get into any fights,” “I don’t misbehave,” “I take my medications” and “my mind is clear.” Greg said he is not suicidal and doesn’t hear any voices. He said, “Most days I am in a good mood and feel good every day.”

Breakfast is at 7 am. Greg said “I don’t mind,… I can do the routine.” Because of Covid, he and his roommates eat in the same building where they sleep, instead of in the dining commons. I asked if he felt safe with Covid spreading around – he said he feels safe, wears a mask and got vaccinated. He shared that some of his peers on his unit had died from Covid. They were kept in a separate unit while they were sick. Greg attended the memorials in the courtyard, and “there was music and talking.”

There are treatment groups every day, but “I don’t feel like going to them and don’t go anymore – it’s no use.” Greg said he followed his treatment – breakfast, lunch and dinner. Medications. Showers. “I make my bed” and “stay out of trouble…. I just stay here” and “learn to adapt.” He tried to do everything right, but having been in the state hospital for so long, he was tired and knew he wasn’t going to get out. He had lost hope.

A Peer Perspective From Outside

As Greg was telling me his story, I felt frustrated, sad and heartbroken. I could understand why he stopped trying - what was the point? After all, he was doing everything he was supposed to do, but was still stuck in that place. I felt really mad and wanted him to feel mad – mad they wouldn’t let him out. But he just seemed to accept it. I couldn’t let go of his feeling of hopelessness.

As a peer advocate, I have always felt there is something we can do to change things. We couldn’t just give up. I wasn’t judging Greg - I just didn’t want him to accept things as they were – why wasn’t he fighting for his freedom?

He said he didn’t even remember doing anything wrong. I felt it wasn’t fair he was locked up for something he didn’t do. At least he didn’t think he did it. That was his reality. It wasn’t right he was being punished based on what “other people” said he did. They say he is “getting treatment,” but there is still a lot about mental health that providers don’t understand. The treatment Greg was getting wasn’t helping him, and I think the 2-story high, reinforced steel and razor wire fence was just one more barrier that kept him from getting better.

After I hung up the phone, I realized that after 41 years living in confinement and being told what to do, Greg was totally institutionalized. He probably didn’t realize the routine and restrictions had broken him down. Like a wild mustang, he had been corralled, tamed and molded into a “model patient.” Beaten down by the system, he knew he was never getting out. I realized, after hearing Greg’s story, I was feeling hopeless, too. And I’m not even the one locked up…

State Hospitals: No Escape from Covid

The California Memorial Project (CMP) honors our peers with mental health disabilities who lived and died in California state institutions. Many were buried in mass or anonymous graves and remain nameless. Plain stone markers with numbers are the only way we know they ever existed.

Even today, many people are still locked away in state hospitals - often unacknowledged, unseen and unheard. It’s easy to forget them. They live in confinement, which is so restrictive, they have no sense of freedom or personal autonomy. They have no sense of control, and their daily decisions are made for them.

The hospital is a secured environment. During this time of the pandemic, everyone is screened (and, at times tested) for Covid before they enter the secure treatment area. But exposures still occur when residents come in contact with staff and new admissions. Who knows what else people bring in with them from outside? They probably don’t realize they put residents at greater risk of getting the virus.

Hospital staff and residents follow safety guidelines to limit the transmission of Covid - they wear masks, regularly wash their hands and most get the vaccine. Housed with over 1000 people, there is no way to social distance. Residents still get sick or die.

When a resident has been exposed to the virus, those living in the same unit are quarantined for 14 days. They can’t leave their units to go to the dining room or access the library or participate in any treatment activities. The common areas are closed. They can’t even open a window to air out their room. No one gets grounds privileges, and they are only allowed to spend a limited amount of time in the courtyard to get fresh air. There is only so much the hospital can do to protect residents against Covid.

The Department of State Hospitals (DSH) keeps track of the number of residents who have tested positive or died due to Covid. Between May 15, 2020, and May 10, 2021, a total of 1897 residents tested positive and 73 residents died during this pandemic at all 5 state hospitals combined. Up-to-date statistics are posted daily on the DSH website.

In 1918 at San Quentin prison, at least 1450 people living in similarly overcrowded conditions and confinement (over 76% of the institution’s 1900 prisoners) reported sick at the height of the Spanish flu outbreak (L. L. Stanley, “Influenza at San Quentin Prison, California,” Public Health Reports 34, no. 19 (May 9, 1919): 996.). This current pandemic and its outcome isn’t any different from 100 years ago. We haven’t learned from our past. Have we learned from the present?

Now that the Covid vaccine is available for residents, many might assume the danger of getting the virus is minimal. But what happens when some other virus or socially communicable disease arises again in the future? It is not a matter of “if,” but “when.” Is there a plan for the next one?

This past year shows there is no escape from another pandemic for residents in state hospitals. Living in a restricted setting is dangerous. It is urgent to create more living options and treatment for people with mental health disabilities so they can recover in the community rather than in confinement.

The CMP also interviewed peers who are former residents of state institutions who returned to live in the community. View their stories below

Once on the Inside, now on the Outside: Stories from our Peers who Lived in a State Institution and Now Live in the Community

Interviewing and collecting personal stories from peers who have lived in a state hospital or developmental center is one of the CMP’s goals. Over the past several years,

As part of the CMP, we interviewed 23 different people to gather first-person accounts about their experiences living in a state institution and recorded their personal stories for our oral history project.

PSA staff met with peers to listen to their stories. Below are excerpts from 2 separate interviews with peers who at one time lived in a locked facility. These interviews are not word-for-word and have been revised and shortened to provide the context and highlights of their experiences. We only share their first names to protect their confidentiality.

Jane

This first interview is with Jane, who was at Napa State Hospital for 4 years:

PSA staff: So Jane, what was going on in your life before you went to the state hospital?

Jane: I fell into a deep depression. I felt lonely and vulnerable and helpless and hopeless and sometimes when I’d cry I’d feel like there was a pool of water around my heart, it was very, very deep. I stopped eating, and I wasn’t feeding my kids.

PSA staff: What happened after that?

Jane: I was in the hospital for two days, and then I was taken to jail. I didn’t feel I was in the hospital long enough.

PSA staff: So then you went to court?

Jane: Yes. I was told by my public defender that I’d be at Napa State Hospital for 6 months to a year and then I’d get out. I ended up being there for 4 years…but I wasn’t being told why I was kept there for so long.

They told me I had a mental illness. At first, when I got there on the locked unit, I was very scared. I saw all these people dressed in khaki. I was scared of that, I don’t know why but I was. I saw there were some people that were being attacked there. I felt in danger there.

PSA staff: I can see why that would have been scary. Did they let you know about your treatments? Like your meds and your groups and your therapy, what you were doing, and why?

Jane: They didn’t exactly let me know. I mean I knew every day what time meds were, if you didn’t take them you’d get in trouble. …I knew I needed to do groups, they told me for treatment, but they didn’t tell me exactly why I needed it.

PSA staff: What about your family and their attitudes towards you?

Jane: Some of my family members didn’t know I was there because I was ashamed. I didn’t call them. My brother was the one that I was talking to at the time. He just let me know he loved me, but he didn’t call me very often. I told him I was ashamed…. And he said you shouldn’t be ashamed…

PSA staff: So there was more stigma on you than other people put on you. I mean you put it on yourself – you had a lot of self-stigma.

Jane: I put it on myself, yeah.

PSA staff: Did you have any moments at the hospital that stood out more than others?

Jane: I was trying for a long time to get a job there. After maybe a year, I finally got a job. I had to start out with sorting and stacking newspapers, which was very low pay.

And then I went to sewing sashays and stuffing pillows and banging them, it was called. I had to bang them to make the stuffing all even inside the pillow. That was also low pay. Eventually, I went to the beauty shop, and they paid minimum wage. And I liked working, so I really liked that.

Also, I liked performing and Taiko drumming. This lady was coming and teaching us how to do it. And we would do performances for people. That was a really good experience for me. I was in the Napa Register newspaper, front page.

PSA staff: Was there ever a time when you considered Napa State Hospital your home?

Jane: No. I was planning on getting out of there, someday. I didn’t know how long it was going to take…

PSA staff: Is there anything you’d like other people to know about the hospital?

Jane: Well, I want them to know that even though your public defender tells you you’ll be there for 6 months to a year, in most cases, you’re there longer, at least 2 years.

PSA staff: What happened after you left the hospital?

Jane: I was discharged from Napa and went to a CONRep program. Then I went to a board and care for 6 months and then I got my own apartment.

PSA staff: So what do you do these days?

Jane: I work at Bradley Video and do data entry and filing. I also attend Lewis Adult School and take Microsoft Word and Excel. So those two things I’m working on at work.

Joan

Another PSA staff member interviewed Joan. At the time of the interview, Joan lived at a board & care facility. She just had her 70th birthday.

PSA staff: So you were in Agnews State Hospital – what was it like?

Joan: I had shock treatments. I was on Thorazine. I was so groggy that I couldn’t even talk! For every word I said, I would have to take a sip of water because I was so over-medicated.

In this place, people yell and scream and carry on and that can be a bit of a shock. If they didn’t give them shock treatment, they were scared they were going to get it, so they behaved themselves.

PSA staff: What was the Agnews campus like?

Joan: They had a chick farm and all the little chicklets would see you walk by and then run back to their mothers.

PSA staff: Were there any treatments you were forced to take?

Joan: Oh yeah! They gave me so many series of shock treatments. My husband said he came to see me and I didn’t recognize him after a certain amount of treatments.

PSA staff: What else would you experience in a typical day?

Joan: You would go and take a shower in the evening and that was very difficult to do because everybody, all these women would line up and it was like mass production, mass production, taking your showers.

This one woman I felt so sorry for her because she had a scar and she had to expose it to everybody. She had the stigma of being mentally ill and nobody would have anything to do with her.

PSA staff: So what are you doing now?

Joan: I want to go into business for myself…

*If anyone wants to share their personal story of having lived in a California institution, please email us at: californiamemorialproject@gmail.com

Looking to the Future: The Legacy of CMP

Today, five state hospitals remain open in California, with an average daily population of about 6,000 people. The CMP reminds us that thousands of people are still institutionalized, in some cases indefinitely, in California state institutions. Our peers who currently live in locked facilities and state institutions are hidden from our view, their voices silenced, their humanity overlooked.

This is still happening to our peers today. The CMP is working to change that by recognizing, acknowledging and respecting the rights and dignity of individuals living today in these institutions against their own wishes.

The CMP’s work extends beyond remembrance. It aims to empower advocacy within communities and influence legislation that honors the lives of all individuals affected by state-run institutions. Projects like the CMP inspire peers and community members to advocate for legislative change, not just for those who died in state hospitals but for individuals affected by institutionalization today.

“Projects like CMP empower peer-like communities to advocate for legislation to pass projects…to honor the lives taken by law enforcement,” Tellez explained. This empowerment is critical to fostering a culture of dignity and respect for vulnerable populations.

The CMP highlights the stigma and discrimination faced by those with disabilities. We educate the public about the importance of voluntary, community-based treatment options that are more effective than the forced treatment our peers received.

With recent California legislation that serves to institutionalize more people with mental health disabilities, it is even more critical that people understand there are alternatives to involuntary hospitalization which honor and respect the rights and dignity of our peers. Now, more than ever, we must disrupt the narratives about disability institutions in the state of California. We need “homes,” not beds in disability institutions.

The CMP envisions the day when all our peers will be recognized and valued for who we are, as people – to be acknowledged and accepted with our limitations and celebrated for our strengths. We envision the future together, beyond stigma and discrimination, neglect, mistreatment, ignorance and judgment. We envision a world where freedom, independence and self-determination and personal autonomy will be a reality for us all… a day when we are all free - free to just be… ourselves.

For more information about CMP,

send an email to: californiamemorialproject@gmail.com

Find out more about our

Peer Self-Advocacy (PSA) Program.