From Navigation to Transformation: Addressing Inequities in California’s Regional Center System Through Community-Led Solutions

From Navigation to Transformation: Addressing Inequities in California’s Regional Center System Through Community-Led Solutions

This policy brief makes the case for community-led solutions to address longstanding racial and ethnic disparities in California’s regional center system and offers four key strategies to make the system more equitable for disabled people of color.

Prepared By: Vivian Haun, William Leiner, and Sabrina Epstein

With Special Thanks To: Chris Acosta, Tho Vinh Banh, Vanessa Cuellar, Rithy Hanh, Emily Ikuta, Teresa Nguyen, Vanessa Ochoa, Vanessa Ramos, Mary Rios, the community members who graciously shared their stories with us, and the people with intellectual and developmental disabilities throughout the state whose lived experiences shape this work.

Click here for a plain language version of the Executive Summary of this policy brief.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Background

- I. Overhaul Policies that Disproportionately Restrict Access to Services for People of Color

- Implementation Strategy: Minimize administrative burdens through improved technology and enable more efficient information sharing across sectors and minimize time- and staff-intensive labor.

- Implementation Strategy: Reexamine the broad amount of discretion regional centers have to interpret and implement the Lanterman Act and identify key decision-making factors or processes that should be standardized.

- II. Hold Regional Centers More Accountable for Reducing Disparities Through Transparency and Funding Requirements.

- III. Strengthen the Impact of Statewide Equity Initiatives by Considering Equity in Program Design, Implementation, and Funding.

- Implementation Strategy: Design and implement new or restored services with an intentional focus on ensuring equitable access to those services.

- Implementation Strategy: Broaden the impact of the Service Access and Equity Grant program by prioritizing the sharing, replication, and scaling of promising practices.

- IV. Rethink What It Means to Partner with the Community and Redistribute Decision-Making Power to Those Most Impacted.

Executive Summary

Data shows that despite years of effort, racial disparities in California’s system for delivering services to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) remain deeply entrenched. But with a recent federal focus on health equity and a new call to embed equity across California state agencies, this year is the time to rethink our previous approaches, pivot, and take new action. To accomplish this, we must uncover and address how structural barriers in the regional center system unequally affect disabled people of color. Two principles guide this work: shifting our focus from navigating the system to transforming it and full partnership with those most affected at every level.

This brief offers four strategies for policy change:

- Overhaul policies that disproportionately restrict access to services for people of color. This includes recognizing the role administrative burdens play in facilitating or limiting access to services, acknowledging that burdens hurt some groups more than others, and investigating how their impact can be minimized and shifted from disabled individuals and families to the systems that serve them. This involves:

- Interrogating the racially disproportionate impact of how “gatekeeping” laws and purchase of service guidelines are implemented, especially those related to the need for individuals to exhaust generic resources before regional centers will consider funding a requested service. Our current system places the onus almost entirely on the disabled person or their family to pursue and prove the unavailability of a requested service from a generic resource. DRC's clients of color consistently cite this bureaucratic process as one of their most significant barriers to accessing services. To break down that barrier, the DD system needs new, more robust referral infrastructure capable of automating, tracking, and following up on referrals electronically and more efficiently.

- Reexamining the broad amount of discretion regional centers have to interpret and implement the Lanterman Act and striking a better balance between state and local control. At regional centers, service authorizations are determined through multiple layers of discretionary decision-making, creating many points where inconsistency and unintended bias can creep in. Identifying key decision-making factors or processes that should be standardized across regional centers could serve as a powerful counter. For example, people of color tell DRC that service coordinators often make assumptions about the availability of unpaid family caregiving for those living in multigenerational homes—assumptions that limit services for people who live with family members, who tend to be disproportionally of color and have lower incomes. Standardized rubrics that prompt a more comprehensive, nuanced review of family circumstances could help minimize such unintended consequences.

- Hold regional centers more accountable for reducing inequity through stronger transparency and funding requirements.

- While we must change practices that have unintended racial consequences, we cannot change practices that we cannot see. Regional centers make certain policies and data points available to the public as required by law. But many practices critical to determining how services and other resources get distributed remain hidden from view, including internal reviews where more complex service authorization decisions are often made. Making regional centers subject to the California Public Records Act would improve the public's ability to review such practices, and to pinpoint structural issues that may be less visible but still significant contributors to racially disparate outcomes.

- Performance-based funding holds tremendous potential for driving regional centers to take greater responsibility for advancing equity. The new Regional Center Performance Measures, which give financial rewards to regional centers that do well on certain metrics, are a good first step. But they can do much more to put equity at their core— for example, by stratifying not just some but all measures by race, ethnicity, and language, and rewarding regional centers whose outcomes for people of color do not significantly lag behind their overall outcomes, to ensure that all people served are benefitting from systemwide improvements. In the future, the state should consider going beyond bonus payments and base a portion of regional centers’ operations budgets on how well they serve their community, as shown by performance metrics.

- Use the Governor’s call to embed equity throughout government to not just consider equity in DD program design and implementation, but to center it, starting with its signature equity initiatives, and by placing greater emphasis on planning for and expanding statewide capacity. The 2021 restoration of social recreation and camping services, and its uneven rollout to date, offer valuable insight into what more the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) can do to build equity into future programs. In addition, the Department’s Service Access and Equity Grant program should build on and expand its impact by targeting underserved communities, promoting the replication of promising practices, and encouraging more scalable cross-sector investments.

- Reimagine what it means to partner with the community, and redistribute power to those most impacted—specifically, disabled people of color. Community-based participatory research should be introduced as a tool to identify problems and develop solutions that are community-led and address the root causes of inequities.

This policy brief is not an exhaustive list of ways that structural racism manifests in the DD system, nor does it seek to accuse anyone of racist intent. Instead, we hope that by confronting structural racism in our system—how our policies, practices, funding and decision-making structures, and cultural norms may unintentionally but repeatedly disadvantage and marginalize disabled people of color—we can make meaningful progress towards a more equitable system.

Introduction

This year presents an unprecedented opportunity for California to move towards justice in its system for serving people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Under an executive order signed by Governor Gavin Newsom in September 2022, all state agencies and departments, including DDS, must “embed equity analysis and considerations in their mission, policies, and practices” for the next three fiscal years, starting in 2023-2024.1 The order requires DDS and other departments to develop strategic plans to address disparities by gathering and analyzing data from “historically underserved and marginalized communities.”

Disability Rights California applauds this historic commitment to centering racial equity in government policies. For Californians with I/DD, its prioritization could not be timelier. The year 2022 saw the release of two advocacy reports finding persistent racial disparities in state spending on services for those served by the developmental services system despite a decade and millions of dollars of investment, an investigation by a state oversight body into state efforts to address disparities, and the publication of two state auditor reports finding that DDS has not done enough to ensure adequate regional center efforts to reduce disparities in the receipt of certain in-home services or to provide adequate oversight of regional centers in general.234

This moment represents our best opportunity in decades to collectively reimagine our DD system. What would it take to have a system where everyone can access what they need to thrive, regardless of their race, language, or background? What changes must we make, and what barriers must we dismantle, to create that system together? We believe two guiding principles are necessary:

- Shifting our focus from navigating the system to transforming it. To date, the state’s efforts to address inequity in the DD system have focused largely on language access and service navigation, making helping people better understand the system its primary mechanism for reducing disparities. However, while these approaches may be necessary for addressing inequity, they have not been sufficient, as they leave in place structures that perpetuate disparities, even when those structures are better understood. To advance equity in a meaningful way, California’s DD system must start confronting and eradicating structural racism in our system-- the ways our laws, policies, practices, and funding structures may unintentionally but repeatedly disadvantage disabled people of color.

- Full partnership with those most affected at every level. People of color served by regional centers are experts in their own lived experiences and the problems their communities face. Advancing equity will require sharing decision-making power with those most affected by disparities— not just by asking for their input, but by treating them as equal partners in identifying root causes and co-creating solutions from the outset.

The following policy brief identifies four key strategies to make the system more equitable: (1) overhauling regional center policies that disproportionately restrict access to services for people of color; (2) holding regional centers more accountable for reducing inequity through stronger transparency and funding requirements; (3) centering equity in the design and implementation of all developmental services programs and initiatives; and (4) reimagining what it means to partner with the community and redistribute power to those most impacted. We identified these topics through qualitative interviews with self-advocates, parents, and community leaders of color, and our experience with DRC clients as California’s protection and advocacy organization.

What is structural racism? Structural racism is “racism [that] is not simply the result of private prejudices held by individuals, but is also produced and reproduced by laws, rules, and practices, sanctioned and even implemented by various levels of government, and embedded in the economic system as well as in cultural and societal norms.”

Zinzi D. Bailey, Justin M. Feldman, and Mary T. Bassett, “How Structural Racism Works — Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities,” New England Journal of Medicine 384, no. 8 (Feb. 25, 2021): 768–73.

The goal of this brief is to spark discussion and suggest ideas for addressing longstanding racial and ethnic disparities in the DD system. However, it is not the place of any one organization to dictate specific solutions. We firmly believe that this work must be led by and center the voices of those affected by the issue, particularly disabled people of color. Accordingly, we hope this brief can serve as a starting point for a process of deeper stakeholder engagement that will lead to long-term, community-led solutions.

Background

DDS serves nearly 400,000 Californians with a variety of developmental disabilities.5 Under the Lanterman Act, Californians with developmental disabilities are entitled to the services they need to lead independent lives in homes and communities of their choice. These services are provided through a network of 21 regional centers. Regional centers are nonprofit organizations that contract with DDS to act as the entry point into the DD system, providing case management through service coordinators to connect people with and fund services that are identified through an individual planning process (IPP).

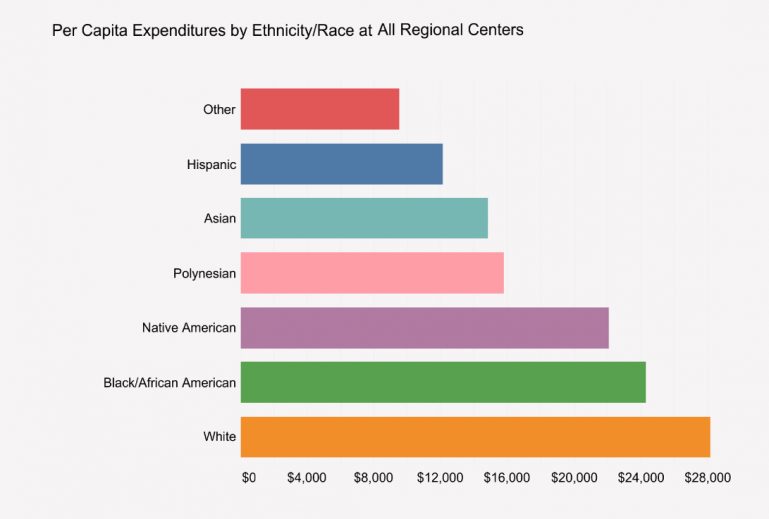

Regional centers do not distribute services equitably to the people they serve. Per capita expenditures for people served by regional centers demonstrate this inequity (Figure 1). People of color receive about half as much per capita spending on their services compared to people who are white.

Figure 1: Per Capita Expenditures by Race and Ethnicity in Regional Centers in FY 2020-20216

Current reform initiatives address aspects of racial and ethnic inequities in regional centers. For example, DDS has invested in language access services to assist people in navigating the system. However, despite years of effort and investment, racial and ethnic disparities in spending on regional center services have barely moved.6 Although the millions in grant funding have been valuable in building local relationships and capacity, they simply have not been enough.

I.) Overhaul Policies that Disproportionately Restrict Access to Services for People of Color.

A.) Implementation Strategy: Minimize administrative burdens through improved technology and enable more efficient information sharing across sectors and minimize time- and staff-intensive labor.

In a 2021 report to President Biden on advancing equity in federal government agencies, the federal Office of Management and Budget described “administrative burdens” as “the onerous experiences that individuals can encounter when trying to access a public benefit,” such as time spent on paperwork, answering notices and phone calls to verify information, navigating web interfaces, and collecting required documentation. The report found that, according to research, “administrative burdens do not fall equally, leading to disproportionate underutilization of critical services and programs, often by the people and communities who need them the most. Burdens that seem minor when designing and implementing a program can have substantial negative effects for individuals already facing scarcity.”7

“The regional center is not there to provide services. The regional center is there to not provide services,” said one mother in an interview. In her experience, the regional center says no at every turn. Because of this, “they totally failed my daughter so my daughter did not progress. If regional center did their job, then my daughter would be better.”

California’s developmental disabilities services (DD) system is no exception to the way administrative burdens exacerbate inequities. Their impact is felt most acutely concerning the Lanterman Act’s requirement that people with I/DD access all “generic” resources –i.e. those available from school districts, private insurance, and publicly funded programs like Medi-Cal and in-home supportive services (IHSS) –before a regional center can purchase services for them. In other words, regional centers are the “payor of last resort.”8 According to the Lanterman Act, regional centers are supposed to help people served and their families access generic resources.9 However, in practice, regional centers typically provide minimal help to clients in navigating generic resources, instead taking a “not it” approach where they tell people to try other agencies first, without providing any help to access the service, or any follow-up to determine if or when the service was in fact obtained.

This practice places the administrative burden of proving that generic resources have been “exhausted” entirely on the disabled individual and/or their family. Depending on the regional center, this could mean obtaining a written denial of their request or pursuing an administrative appeal of such a denial. Often, when people encounter difficulty navigating other systems, regional centers respond by telling them to “keep trying,” resulting in months- or years-long delays in getting services, or all too often, in no services at all after giving up due to overwhelm.

A self-advocate described how he had to educate himself on all the programs that were available to him. He said that when service coordinators do your IPP, it’s always repetitive. They don’t necessarily let folks know what they can offer. He feels that the coordinators are “sabotaging” him by not doing the job they’re supposed to be doing. There’s also a language barrier – oftentimes people don’t know the specific word regarding a service, they can’t translate, so they “drop it,” rather than trying to expand and deliver the message.

“All wrong door” practices like this have a disproportionate effect on people of color with I/DD, many of whom already rely on comprehension, communication, or other functional supports, and often do not have the time or resources to jump through the many hoops required by regional centers to prove that the service at issue is not available to them. Recent reports about the broader social services system show that this administrative burden on disabled people and their families is dehumanizing and harmful, and disproportionately results in disabled people of color receiving fewer services.1011 Moreover, data on referrals to generic resources and their completion or response rates are not a required field on most IPPs, and thus are not collected or tracked by regional centers consistently. As a result, California has very limited ability to identify larger trends around which generic resource agencies people are referred to, how often services are actually obtained from those generic resources, and/or how long it may take for individuals to receive services following a referral.

More must be done to track and minimize administrative burdens in the DD system, but the current options for doing so are limited by DDS and regional centers’ existing, decades-old information technology (IT) system. As such, the state should invest in technology that would enable regional centers to track generic resource referrals in real-time, making it easier to “close the loop” about the outcome of that referral. Closed-loop referrals would automate much of a referral process traditionally done through case-by-case phone calls and emails, making following up on referrals to generic resources quicker and easier for both disabled individuals and their service coordinators. It would also provide valuable systems-level data as to where the most significant cross-sector service gaps may be and make it possible to someday develop a performance measure for regional centers on the timeliness of service authorization following a request.

Similar models are being used in other states, as both Arizona12 and North Carolina13 have recently implemented new IT systems with closed-loop referral capacity. California, too, has recognized the importance of sharing data across the health and human services sector with its Data Exchange Framework, a statewide data-sharing agreement that will enable and expand the exchange of information among health care entities, government agencies, and social service programs in 2023 and 2024.14

Another parent tried to get treatment for her son’s eye problem, which is related to his developmental disability. Between having to go back and forth with Medi-Cal and the service coordinator repeatedly to show that there was no one in the Medi-Cal network who provided the needed therapy, the care was delayed by two years.

An updated IT system also opens a window of opportunity for developing and adopting an IPP template for use statewide. A similar effort in California’s special education sector took place under the Budget Act of 2020 (Senate Bill 74), which created a stakeholder workgroup to design a “state standardized individualized education program (IEP) template.”15 A comparable process could be used to develop a statewide IPP template that, in contrast to current IPP forms whose formats vary across regional centers, would make the collection of closed-loop referral (and other) data vastly more uniform and efficient by requiring and standardizing electronic IPP data collection fields across regional centers.

The introduction of the California Data Exchange Framework, along with recent steps by DDS to modernize its IT systems, presents a timely opportunity to make closed-loop referrals a reality.16 Doing so would place the onus of pursuing and proving the unavailability of a requested service on a systems-level process and reduce the barriers that disabled people and communities of color face when attempting to access regional center services.

B.) Implementation Strategy: Reexamine the broad amount of discretion regional centers have to interpret and implement the Lanterman Act and identify key decision-making factors or processes that should be standardized.

In California’s developmental disabilities service delivery system, decisions about the type and amount of services people receive are supposed to be made through the IPP team process, which includes the person served, a regional center service coordinator, and others at the person’s request. However, in practice, those decisions are largely shaped through multiple layers of regional center discretion outside the IPP process. The number of layers, amount of discretion, and lack of transparency into how that discretion is exercised all contribute to the unequal treatment and disparities we see in our system.

While the IPP team is required to discuss the person’s needs, choices, and goals, and then decide as a team which services and supports will best help the individual achieve them, several external factors, defined largely or entirely by the regional center, play a major role in driving those decisions:

- Each regional center develops its own set of purchase of service policies that govern how and under what circumstances the regional center may approve a particular service, such as assistive technology, family supports, housing assistance, or respite. These policies often state that there is an “exception process” for requests that fall outside the stated parameters, without further detail about this process.

- As part of the IPP process, the regional center is responsible for “gathering information and conducting assessments” to help make decisions about services.17 But there are no consistent or transparent standards governing the process regional centers use to gather information or conduct assessments. As a result, decisions about what information will be relied upon, when assessments may be required, and what assessment tools will be used are left to the discretion of each regional center.

- Critical decisions about a person’s life are often made outside the IPP process through internal review committees. These committees were created by statute to ensure adherence to legal requirements and greater internal consistency with regional center policies. However, they make opaque decisions outside the presence of the person served and ultimately supplant the role of the IPP team. While internal reviews are generally reserved for less routine, more complex service requests, the circumstances that trigger them are unclear and vary by regional center.

Furthermore, although regional centers are required to publicly post their purchase of service policies, the same requirements do not hold true for all the assessment procedures or tools that regional centers use to operationalize these policies. Nor do they apply to any guidelines that may be used by internal review committees that make service determinations outside of IPP teams. Due to this lack of transparency or consistency, each layer of discretion becomes another decision-making point that can potentially and inadvertently contribute to racially disparate outcomes.

A parent shared that her friend, whose child has similar disabilities but is white, gets much more services from the regional center than her daughter. She felt that because of her race and English not being her first language, she did not know the right way to ask for things from the regional center. She said, “When my white friend asks for the service she knows how to articulate it much better and ask very politely and tell them it is her right.” Instead, when this parent asked for more services, she was told that “at least she gets respite.”

To counter such biases, California should look for ways to standardize service authorization criteria, to ground them more intentionally and consistently in core equitable principles. Other states use service determination tools that allocate services more equitably, share information with providers more consistently, and minimize unnecessary repetition.18 A stakeholder process should determine exactly which factors, processes, and/or layers of decision-making should be more standardized, and to what degree. Standard decision-making criteria should consciously aim to minimize the burden and maximize access to underserved communities. At the same time, the criteria must still be flexible enough to account for individual differences.

To illustrate, natural supports are one area where standardization could reduce disparate policy effects. Natural supports are frequently used as a reason to deny requested services. Purchase of service policies generally require that, before purchasing a service, a regional center must pursue all other sources of available services or funding, including natural supports. In other words, regional centers do not need to fund a service or support to address a disabled person’s needs if those needs can be met through a natural support, such as family members, friends, or other acquaintances in the community.

One family member shared that their older son did not go to college out of state because he wanted to be available to provide care for his younger brother. Additionally, the mother left work, saying “With my background and my experience organizing and getting services is really part of what I do well. However, this was a completely new arena and so overwhelming that I could not return to my career, and I think that’s important. Our experience doesn’t only affect the child, but how it impacts the family. I went from a middle-class income to qualifying for the federal poverty level.”

Purchase of service policies typically include language echoing federal Medicaid regulations, which state that natural supports must be voluntary, not compelled.19 Individuals served by regional centers are supposed to decide the extent to which natural supports are utilized, and family members’ availability to assist is supposed to be taken into account.

However, our clients and other community members report that regional centers routinely deny requests for services—such as transportation or personal assistance to support their ability to participate in their community-- once they learn that the individual lives at home with other adult family members, without considering whether the family member is willing or available to play this role. When a person lives with family members, regional centers default to assuming that the other adults can provide support and therefore it would not be cost-effective to fund the requested service. This assumption is typically made without any structured evaluation of the family’s specific circumstances.

Involuntarily compelling family assistance in this manner not only contradicts federal regulations and purchase of service policies but also disproportionally impacts people of color, who are more likely to live in multi-generational homes.20 While cultural values are a key factor, more and more people who share residences with family members are forced into doing so due to the lack of affordable housing in California, sometimes in overcrowded conditions. Those who do are increasingly and disproportionally lower-income and/or from communities of color.21

California could mitigate such disparate impacts by using a standardized rubric for determining whether natural supports are genuinely available to support the disabled person. For example, many states utilize caregiver assessments that consider more nuanced and family-centered factors, such as whether the family member is a single parent, other caregiving responsibilities they may have, their employment status and work hours, whether they may be the sole breadwinner in the household, their physical and mental health and capacity, their access to transportation, and the type of support needed.22 A tool of this kind would not only specify the relevant criteria to consider, but it would also prompt service coordinators to gather, document, and systematically evaluate those factors. Through clear, consistent criteria linking service determinations more to actual need than to characteristics correlated highly with race, standardization can play a key role in addressing service access disparities.

II.) Hold Regional Centers More Accountable for Reducing Disparities Through Transparency and Funding Requirements.

A.) Implementation Strategy: Require regional centers to comply with the California Public Records Act.

Even though regional centers carry out core governmental functions with state and federal funds, they are exempt from transparency laws such as the California Public Records Act. The limited statutory disclosure provisions that do exist do not provide enough of a window into the totality of how regional centers make service authorization decisions. For example, regional centers are currently only required to publicly post guidelines and assessment tools related to respite, transportation, personal assistance, or independent or supported living service needs.23 These services constitute a small fraction of those available under the Lanterman Act.24 Additionally, although it is possible to seek public records from DDS, DDS is only required to collect printed purchase of service policies and other policies, guidelines, or assessment tools utilized by regional centers.25 These limitations obscure the full picture of how service needs are determined, making it difficult to identify and change the policies and practices that systematically and disproportionally restrict service access for communities of color. While we must change practices that contribute to inequities, we cannot change practices that we cannot see.

Requiring regional centers to comply with the California Public Records Act has been a longstanding point of discussion. Most recently, legislation that would have required regional centers to comply with the California Public Records Act was introduced in 2010. Concerns were raised at the time that the legislation may not withstand legal scrutiny and that it may open the possibility for other nonprofit agencies to be subject to the California Public Records Act.26 In recent years, however, the Legislature27 and the courts28 have taken a more nuanced, fact-specific approach to this issue in similar contexts, lending credence to the idea that regional centers should no longer be shielded from transparency laws.

For example, in 2019, the Legislature amended the California Education Code to require charter schools to follow the California Public Records Act and other transparency laws.29 Like charter schools, regional centers are statutorily created and publicly funded nonprofit corporations under contract to perform core governmental functions.

Moreover, a California Court of Appeal case decided in 2022 suggests that this action could withstand legal scrutiny. In The Community Action Agency of Butte County v. The Superior Court of Butte County, the California Court of Appeal established a 4-factor test in order to determine whether a nonprofit agency is subject to the Act.30 The 4-factor test asks: (1) whether the entity performs a government function, (2) the extent to which the government funds the entity's activities, (3) the extent of government involvement in the entity's activities, and (4) whether the entity was created by the government.”31 This new framework potentially dispels prior concerns, and underscores the justification for making regional centers subject to the state’s transparency laws.

B.) Implementation Strategy: Use performance-based funding to drive racial equity goals and hold regional centers more accountable for addressing disparities.

In recent years, health and human services systems in California and across the country have increasingly turned to payment incentives and funding reforms as a critical lever for advancing racial equity. States have started paying local health networks more for showing progress in narrowing disparities, achieving other equity metrics, investing in communities that have been the most affected by racial inequities, and building their capacity to provide more culturally and linguistically appropriate care. While applying these tools to the provision of home and community-based services (HCBS) remains relatively new, especially for people with I/DD, the Governor’s call for racial justice demands a new and more urgent level of consideration in the way California funds its regional centers.

DDS has taken a step toward incentivizing more specific outcomes through its recent implementation of the Regional Center Performance Measures, which are designed to award financial bonuses for meeting specific metrics. Two of the ten current measures address “Equity and Cultural Competency” by examining the number or percentage of people served who report that service coordinators communicate with them in their preferred language and respect their culture. A third measure related to the timeliness of Early Start intakes states explicitly that its data will be “stratified by language, race, and ethnicity,” but is the only one of the ten measures to do so.32

While these steps are welcome and have yet to be fully implemented, their ability to effect meaningful change may be limited. To date, the bonus payment amounts tied to each measure have not been made public, and it remains unclear what amount would be enough to motivate a regional center to meaningfully reprioritize its activities. More importantly, the measures’ limited focus on the linguistic and cultural competency of service coordinators and Early Start access fails to address regional center “gatekeeping” policies and practices around service authorization that affect purchase of service spending more directly.

In the near term, DDS could leverage the Regional Center Performance Measures for equity more effectively by stratifying more measures by race, ethnicity, and language, and financially rewarding regional centers that either (a) perform to a certain standard on those metrics across all racial groups, or (b) show minimal gaps in performance between white and non-white people served by regional centers. Such an approach would broaden the DD system’s current and narrow focus on purchase of service expenditure disparities as its primary measure of racial equity. While spending gaps yield useful data on differential treatment by race, they are a weak proxy for the more foundational issue of the extent to which all Californians with I/DD are accessing the supports they need to thrive, regardless of their race, ethnicity, or language. We can obtain richer, more comprehensive data on that front by shifting our emphasis away from how much is spent on white people towards how well different groups do on specific measures of access, service coordination, service delivery, and individual experience.

To truly hold regional centers more accountable for their role in perpetuating or dismantling disparities long-term, California needs to look beyond the existing regional center performance measures to other funding structures being used to drive desired outcomes. For example, the current statute requires that starting in July 2024, 10% of the payment structure for service providers in the DD system must be based on how well providers meet specified measures of service quality.33 Similarly, California should implement funding reform that would base a portion of regional center operations budgets on their performance on equity measures. One model to look to is the one currently used by California’s community college system, where 10% of funding is determined by each college’s performance on equity-based measures that were co-developed with key stakeholders, and 20% is based on the number of high-need students enrolled.34 Doing so would create strong incentives for regional centers to identify and invest in efforts that promote equity.

III.) Strengthen the Impact of Statewide Equity Initiatives by Considering Equity in Program Design, Implementation, and Funding.

A.) Implementation Strategy: Design and implement new or restored services with an intentional focus on ensuring equitable access to those services.

In 2021, the Legislature restored the ability of regional centers to pay for social recreation and camping services after more than a decade of suspension. Advocates heralded this for two reasons. First, a lack of access to healthy and stimulating recreational experiences can lead to negative health and social outcomes, with more acute effects for families with limited resources. Second, the suspension of social recreation and camping programs over a decade ago disproportionately impacted people of color, who were more likely to rely on regional center funding for these services. The restoration of these services was one of the few DDS initiatives squarely understood to address disparities by increasing spending on new services for the people who need them most.

Over a year and a half since their restoration on July 1, 2021, many families are still struggling to access these services. In an October 7, 2021 directive to regional center executive directors, DDS requested that regional centers conduct outreach regarding these services, including to non-English-speaking individuals and communities of color.35 However, the directive did not explicitly emphasize increased access for underserved communities, or the reduction of racial purchase of service disparities more broadly, as a guiding priority or policy goal. As a result, regional centers have adopted, and DDS has approved, purchase of service policies on social recreation and camping services that are having the effect of restricting access for the very communities that were supposed to have benefitted the most. For example, we are aware of regional centers that:

- Categorically refuse to fund transportation to camping and social recreation for children without regard for their family’s actual access to reliable transportation, deeming such transportation a “parental responsibility.”

- Categorically refuse to fund aides or other supports necessary for people to participate in social recreation activities or camping because such support should be “parental responsibility,” regardless of whether the parent is available and able to provide such support.

- Require the reduction of one hour of respite services for every hour of approved camping or social recreation, without regard to the person’s needs.

- Deny requests to assume funding of social recreation activities for children that parents have initially paid for because the child is already receiving the service.

A self-advocate shared that when she asked her service coordinator for more services, they said “oh you’re asking for too much.” She told us, “I felt like I had to do all the legwork” and was still left without respite or social recreation services that she felt would help her. When she advocates for herself, she says that the service coordinators respond with “okay, I’ll get back to you, I’ll get back to you,” and these gaps in communication cause delays in services.

Further limiting access statewide are two significant barriers: the misalignment between the regional center and provider payment structures and the lack of vendorized social recreation and camping providers. First, the way regional centers are set up to pay vendors, which is by invoice after services have been rendered, is at odds with the way most community-based social recreation and camping providers require payment, which is upfront before or at the start of a program. As a result, we understand that as a practical matter, many social recreation and camping activities are only available to families who can afford to pay for them out of pocket and get reimbursed by their regional center later, putting them out of reach for lower-income families who are disproportionally more likely to be from communities of color.

Second, cumbersome vendorization requirements have proven a major barrier to having an adequate network of social recreation and camping vendors. Most community-based organizations that provide these services in integrated settings, such as city recreation and parks departments or private dance studios, serve the general public and are not specific to people with disabilities. Becoming a vendor would enable them to be paid directly by regional centers for providing this service. However, when invited to become vendors, many providers decline due to the bureaucratic nature of the vendorization process, which can take months to complete, currently involves different applications for different regional centers, and would apply to just a tiny fraction of their total clientele. This has severely limited access to social recreation and camping programs. For example, the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks, the largest provider of social recreation and camping services to children in Los Angeles, has so far not been willing to become a regional center vendor.

According to a parent and community leader, the requirement that families pay upfront for social recreation makes it very inequitable. Although she got approval for the service, she says it took her five months to get reimbursed for the first month of social recreation. For families that do not have the money month-to-month, the delayed pay puts the service out of reach. “We are very busy with our kids,” which adds to the challenge of chasing down payment from the regional center.

We understand that many regional centers have worked diligently with the Association of Regional Center Agencies and DDS to address these problems by intensifying their outreach to potential providers, attempting to find ways to expedite the vendorization process, and/or seeking creative ways for providers to be paid upfront. The Department’s recent decision to develop a statewide vendorization process should ease some provider adequacy issues and is a step in the right direction. However, these systemic problems require more systemic solutions that have been slow to materialize. Lack of urgency around purchase of service policies has also limited access, as service coordinators are often conservative or inconsistent in authorizing services without such guidance. Draft purchase of service policies and community outreach plans were not requested until October 7, 2021, and were not due to DDS until December 15, 2021, nearly 6 months after restoration. As of June 20, 2022, nearly a full year after restoration, only 7 of the 21 regional centers had approved purchase of service policies available online.

The uneven rollout of social recreation and camping services poses some lessons for the implementation of future initiatives aimed at reducing disparities:

- Submission, review, and approval of necessary purchase of service policies should be prioritized and expedited so that all regional centers have them in place promptly, within months from launch, with basic direction from DDS to guide service authorization in the interim until policies can be finalized. Regional centers should be directed to develop purchase of service policies with a specific intent to make it easier, not harder, for communities of color to access services, through deeper collaboration with those communities. DDS should use a similar lens and collaborative community process for reviewing and approving these policies.

- An adequate network of providers is a critical component for ensuring service access that takes time to develop. To make sure that enough culturally responsive providers will be available when and where people of color need them, DDS should start researching, planning for, and investing in network adequacy at a statewide level early in the process.

B.) Implementation Strategy: Broaden the impact of the Service Access and Equity Grant program by prioritizing the sharing, replication, and scaling of promising practices.

For many years, DDS’s Service Access and Equity Grants have provided valuable support to community-based organizations’ efforts to tackle racial disparities. However, the grants have been limited in scope in several ways.

First, grant criteria have focused mainly on how to help communities of color better understand and navigate existing systems, rather than on how systems can change their practices to be more accessible and responsive to communities of color. This limited focus has been reflected in the program’s repeated investments in projects for individual community-based organizations instead of broader projects aimed at building collaboration and alignment across organizations.

One grant recipient shared with us that although they were grateful for the funding that enabled them to do this essential work, the year-to-year nature of the grant program made it difficult to plan. The organization cannot grow, plan strategically, or pilot new programs when they do not know whether they will be funded next year. The community leaders also discussed that because they have to spend so much time proving to DDS that their program works in order to secure the next year’s funding, they have less time to actually run the programs.

Additionally, most grants are awarded on an annual basis only, limiting grantees to shorter-term projects that can be conducted over the course of a year, rather than the kind of longer-term, multi-year grant projects that are better suited for implementation of deeper and more lasting change.

To date, the grant criteria have also not identified or prioritized areas of greatest need within purchase of service disparities, or within the awarding of the grants themselves— for example, geographic areas or ethnic/linguistic communities that have never applied for or received grant funding, or certain types of services that have been significantly under-authorized or under-utilized in specific communities.

Lastly, little has been done to promote the sharing of promising practices and lessons learned with the rest of the DD community. As a result, we are missing opportunities to spur and spread innovation more widely across the sector.

We recommend the following to help broaden the grants’ scope and impact:

- The grant program should prioritize partnerships between community-based organizations and regional centers that identify policies and practices that may be burdening and otherwise negatively impacting groups in racially disproportional ways, and then redesign them to be more responsive to the needs of impacted communities. To the degree that grants continue going to community navigation and/or language access projects, DDS should give higher priority to proposals that focus on cross-agency and/or cross-sector training, collaboration, and referral pathways at a systems (not just an individual) level, along with other approaches to breaking down cross-sector silos in culturally responsive ways.

- DDS should prioritize awarding multi-year grants, especially for previous grantees with demonstrated track records of success, to encourage the expansion of promising pilots and practices.

- DDS should identify which communities have been most underserved by previous grants, as well as critical gaps in the types of services that communities of color have traditionally accessed, and incentivize grant awards accordingly—for example, through awarding increased funding and/or more points in grant scoring for proposals focused on these areas.

- The grant program should reward experiments in widening the reach of a previously demonstrated model—for example, by replicating a project in a different ethnic community or expanding it to another regional center. Another focal point could be capacity building across the sector, such as public grantee reflection and dissemination activities aimed at promoting promising models, or peer-to-peer technical assistance cohorts where successful grantees could be funded to support peer organizations in launching their version of a project “in the field” in real time.

IV.) Rethink What It Means to Partner with the Community and Redistribute Decision-Making Power to Those Most Impacted.

A.) Implementation Strategy: Introduce participatory strategies that promote shared decision-making between government and the community served, especially community-based participatory research that engages people of color served by regional centers as full partners in co-identifying problems and solutions.

As co-director of the Cornell Center for Health Equity Jamila Michener notes, “Equity and voice are intertwined, because policy processes that incorporate the voices of people of color are better positioned to facilitate racially equitable outcomes.”36 Incorporating the voices of people of color is crucial for DDS’s response to Governor Newsom’s recent executive order on equity, which requires departments and agencies to “engage and gather input from California communities that have been historically disadvantaged and underserved within the scope of policies or programs administered... by the [department]” in developing strategic plans for the 2023-24, 2024-25, and 2025-26 fiscal years.37

We must take the Governor’s call for equity as an imperative to center the expertise of people of color with I/DD in the development of DDS’s strategic plans. To ensure this, California should invest in a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to analyze and make recommendations regarding the root causes of racial disparities in purchase of service expenditures.

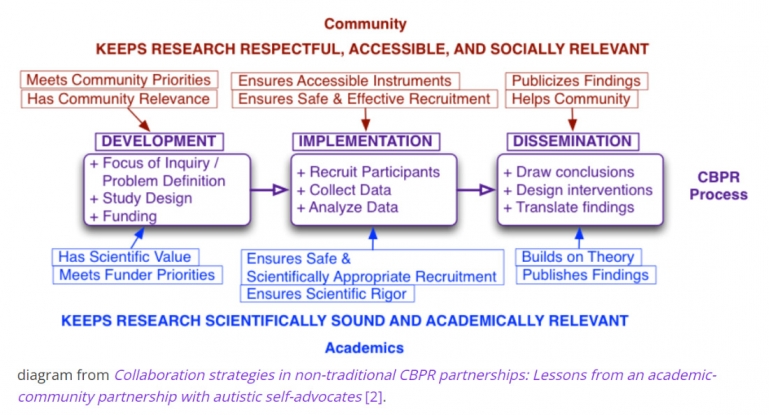

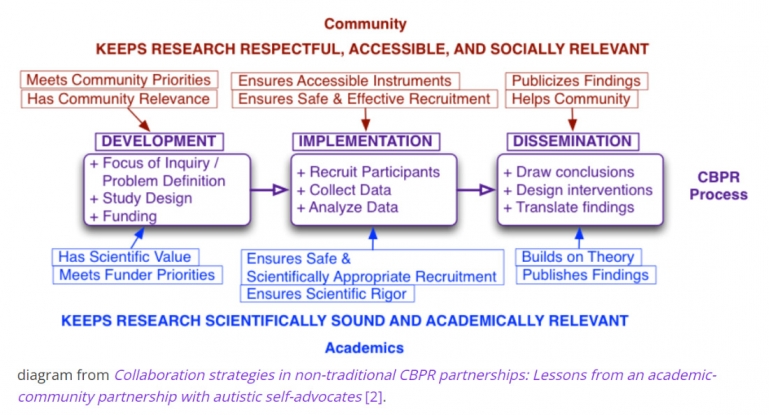

CBPR is a well-established model that has been used to address equity in health and human services, including reducing mental health disparities in California.38 CBPR is specifically designed to bring the voices of historically marginalized populations to decision-making.39 40 CBPR projects are designed and led by community members who collaborate with professional researchers on research design and execution (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Community-Based Participatory Research Diagram

CBPR does more than treat community members as data points to analyze. Instead, it engages them as co-directors and equal partners in all steps of the research process. In doing so, CBPR helps ensure that research-based recommendations have credibility with the community and respond to their needs by fostering a sense of shared ownership from the outset.41

Additionally, CBPR has proven to be an effective approach for eliciting and amplifying the perspectives of people with I/DD, particularly autism, whose voices have been significantly underrepresented in both research and policy development.42 43 This is sorely needed in our DD system, where community engagement has focused primarily on other stakeholders. Although a few self-advocates are typically included, membership in workgroups and advisory committees consists overwhelmingly of service providers and family members of people served by regional centers. A CBPR study would prioritize and provide a framework for ensuring that the Department’s equity analysis and subsequent policy changes are driven by those with firsthand lived experience.

Finally, a CBPR study would build on related research already underway to create a completer and more actionable roadmap for reducing racial disparities. In 2023, we expect the completion of a report that the Legislature commissioned in 2021 to evaluate the state’s Service Access and Equity Grant projects since 2016. While the study will undoubtedly provide important insight, its scope is limited by statute to grant projects which, as described above, have focused largely on service navigation and language access projects run by community-based organizations at a local scale. A CBPR study would provide a fuller picture by providing a vehicle to investigate the ways DDS and regional center policies differentially allocate burdens and benefits among racial groups. The solutions that CBPR points to would also be community-led and already have a high level of community buy-in, easing the path toward implementation.

Beyond a single CBPR study, we strongly encourage DDS and regional centers to adopt similar participatory action models for operationalizing their efforts on equity. For example, this brief earlier suggested engaging communities of color to determine where and for what processes greater standardization may be warranted. A CBPR-like approach would be ideal for such an initiative. Any process that empowers people of color served by regional centers to set agendas and make decisions regarding the allocation of resources will move the DD system further toward racial and disability justice.

- 1. Newsom, G. Executive Order N-16-22. Sacramento, California: Executive Department, State of California, 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/9.13.22-EO-N-16-22-Equity.pdf?emrc=c11513

- 2. Public Counsel. Examining Racial and Ethnic Inequities Among Children Served Under California’s Developmental Services System: Where Things Currently Stand. Los Angeles, CA: Public Counsel, 2022. Available from: https://publiccounsel.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Disparity-Report_Californai-developmental-services_regional-centers.pdf

- 3. Disability Voices United. A Matter of Race and Place: Racial and Geographic Disparities Within California’s Regional Centers Serving Adults with Developmental Disabilities. Los Angeles, California: Disability Voices United, 2022. Available from: https://disabilityvoicesunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/A-Matter-of-Race-and-Place.pdf

- 4. Auditor of the State of California. In-Home Respite Services: The Department of Developmental Services Has Not Adequately Reduced Barriers to Some Families’ Use of In-Home Respite Services. Sacramento, California: Auditor of the State of California, 2022. Available from: https://auditor.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2021-120.pdf

- 5. Department of Developmental Services. Fact Book, 15th Edition. Sacramento, California: DDS, 2019.

- 6. Department of Developmental Services. Regional Center Oversight Dashboard: Purchase of Service Data. Sacramento, California: DDS, 2021. Available from: https://www.dds.ca.gov/rc/dashboard/purchase-of-service-report/ethnicity-race/

- 7. Young, S. Meeting a Milestone of President Biden’s Whole-of-Government Equity Agenda. Washington, DC: Biden White House, 2021. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2021/08/06/meeting-a-milestone-of-president-bidens-whole-of-government-equity-agenda/

- 8. California Welfare and Institutions Code Section 4644.

- 9. California Welfare and Institutions Code Section 4659(d)(2).

- 10. Schweitzer, J., E. DiMatteo, N. Buffie. How Dehumanizing Administrative Burdens Harm Disabled People. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2022. Available from: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-dehumanizing-administrative-burdens-harm-disabled-people

- 11. Wilke, S., J. Wagner, F. Erzouki, et al. States Can Reduce Medicaid’s Administrative Burdens to Advance Health and Racial Equity. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2022. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-can-reduce-medicaids-administrative-burdens-to-advance-health-and-racial#:~:text=ACA%20Reduced%20Medicaid's%20Administrative%20Burdens,the%20home%2C%20starting%20in%202014

- 12. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. Statewide Closed-Loop Referral System. Phoenix, AZ: AHCCCS, 2022. Available from: https://www.azahcccs.gov/AHCCCS/Initiatives/AHCCCSWPCI/closedloopreferralsystem.html

- 13. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. NCCARE360. Raleigh, NC: NCDHHS, 2022. Available from: https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/nccare360

- 14. California Department of Health and Human Services. Data Exchange Framework. Sacramento, California: CalHHS, 2022. Available from: https://www.chhs.ca.gov/data-exchange-framework/

- 15. Sacramento County Office of Education. California Statewide Individualized Program Plan (IEP) Workgroup Report. Sacramento, California: SCOE, 2021. Available from: https://www.scoe.net/media/ankhexys/ca_iep_workgroup_report.pdf

- 16. California Department of Health Care Services. Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Spending Plan: Quarterly Reporting. Sacramento, California: DHCS, 2021. Available from: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/Documents/HCBS-Spending-Plan-Q2-Final-Report.pdf

- 17. California Welfare and Institutions Code Section 4646.

- 18. US Government Accountability Office. CMS Should Take Additional Steps to Improve Assessments of Individuals’ Needs for Home- and Community-Based Services. Washington, DC: GAO, 2017. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-103.pdf

- 19. Carlson, E. Voluntary Means Voluntary: Coordinating Medicaid HCBS with Family Assistance. Washington, DC: Justice in Aging, 2016. Available from: https://www.justiceinaging.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Voluntary-Means-Voluntary-Coordinating-Medicaid-HCBS-with-Family-Assistance.pdf

- 20. Senate Human Services Committee. Moving Toward Equity: Addressing Disparities In Services Provided by the Regional Center System. Sacramento, California: California Senate, 2017. Available from: https://shum.senate.ca.gov/sites/shum.senate.ca.gov/files/03-14-2017_heraing_background_paper_final.pdf

- 21. Cilia, A. The Family Regulation System: Why Those Committed to Racial Justice Must Interrogate It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, 2021. Available from: https://harvardcrcl.org/the-family-regulation-system-why-those-committed-to-racial-justice-must-interrogate-it/

- 22. Kelly, K., N. Wolfe, M.J. Gibson, et al. Listening to Family Caregivers: The Need to Include Family Caregiver Assessment in Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Service Waiver Programs. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute, 2013.

- 23. California Welfare and Institutions Code Sections 4690.2(c), 4629.5(b)(5)].

- 24. California Welfare and Institutions Code Sections 4512(b), 4685(c)]

- 25. California Welfare and Institutions Code Section 4434.

- 26. Assembly Committee on Governmental Organization. Assembly Bill 2220, Subject: Regional Centers, Public Records. Sacramento, California: California State Assembly, 2010. Available from: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billAnalysisClient.xhtml?bill_id=200920100AB2220#

- 27. California Senate Bill 126. Sacramento, California: California State Senate, 2019.

- 28. Community Action Agency of Butte County v. The Superior Court of Butte County, 79 Cal.App.5th 221. 2022.

- 29. California Senate Bill 126. Sacramento, California: California State Senate, 2019.

- 30. Community Action Agency of Butte County v. The Superior Court of Butte County, 79 Cal.App.5th 221. 2022.

- 31. California Welfare and Institutions Code Section 4434.

- 32. Department of Developmental Services. Regional Center Performance Measures: Early Start, Timely Access. Sacramento, California: DDS, 2022. Available from: https://www.dds.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Regional_Center_Performance_Measures_Early_Start_Timely_Access_12132022.pdf

- 33. Department of Developmental Services. Quality Incentive Program (QIP). Sacramento, California: DDS, 2022. Available from: Department of Developmental Services. Regional Center Performance Measures: Early Start, Timely Access. Sacramento, California: DDS, 2022. Available from: https://www.dds.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Regional_Center_Performance_Measures_Early_Start_Timely_Access_12132022.pdf

- 34. California Community Colleges. Student Centered Funding Formula. Sacramento, California: CCC, 2022. Available from: https://www.cccco.edu/About-Us/Chancellors-Office/Divisions/College-Finance-and-Facilities-Planning/Student-Centered-Funding-Formula (For example, the state could also consider basing 20% of regional center operations funding on a proxy measure of need/risk within each regional center catchment area, such as the California Poverty Measure or the California Healthy Places Index.)

- 35. Department of Developmental Services. Restoration of Camping, Social Recreation, and Other Services per Welfare and Institutions Code Section 4648.5. Sacramento, California: DDS, 2021. Available from: https://www.dds.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Restoration-of-Camping-Social-Recreation-and-Other-Services.pdf

- 36. Michener, J. A Racial Equity Framework for Assessing Health Policy. Washington, DC: The Commonwealth Fund, 2022. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/jan/racial-equity-framework-assessing-health-policy

- 37. Newsom, G. Executive Order N-16-22. Sacramento, California: Executive Department, State of California, 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/9.13.22-EO-N-16-22-Equity.pdf?emrc=c11513

- 38. Center for Reducing Health Disparities. California Reducing Disparities Project. Davis, California: UC Davis Health: 2022. Available from: https://health.ucdavis.edu/crhd/projects/crdp

- 39. Cacari-Stone L., Wallerstein N., Garcia A.P., et al. The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: a conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. Am J Public Health. 2014 Sep;104(9):1615-23. Available from: https://doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301961

- 40. Brown, E. R., Holtby, S., Zahnd, E., et al. Community-based participatory research in the California Health Interview Survey. Preventing chronic disease, 2(4), A03, 2005. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1435701/

- 41. Brown, E. R., Holtby, S., Zahnd, E., et al. Community-based participatory research in the California Health Interview Survey. Preventing chronic disease, 2(4), A03, 2005. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1435701/

- 42. Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., McDonald, K., et al. Collaboration strategies in nontraditional community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons from an academic−community partnership with autistic self-advocates. Progress in community health partnerships : research, education, and action, 5(2), 143–150: 2011. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2011.0022

- 43. Keating, C.T. Participatory Autism Research: How Consultation Benefits Everyone. Front. Psychol., Sec. Developmental Psychology: 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713982