Unmasking Policing in Veterans Healthcare

Unmasking Policing in Veterans Healthcare

The Veterans Affairs Police Department (VAPD) of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is one of the ten largest federal administrative law enforcement agencies in the country.

Unmasking Policing in Veterans Healthcare Advocating for Equitable Access to Services for Disabled and Unhoused Veterans

Claire Canestrino, UCLA Veterans Justice Clinic Student

Kimberly Chantal Welch, UCLA Veterans Justice Clinic Student

Sunita Patel, Assistant Professor & Faculty Director, UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic

Aisha Novasky, Senior Attorney, Disability Rights California, Civil Rights Practice Group

The Veterans Affairs Police Department (VAPD) of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is one of the ten largest federal administrative law enforcement agencies in the country.1 As detailed in this report, the VAPD officers play a significant role in veteran patients' healthcare. Because of this role, advocates are concerned that the VAPD is inappropriately enmeshed in a veteran's experience on VA campuses. The statistical and narrative data in this report demonstrate how VAPD officers’ use of discretion and over-involvement in VA healthcare leads to violent interactions between the VAPD and veterans seeking services on VA campuses.2

Table of Contents

Introduction

The VAPD practices detailed in this report may deter veterans from seeking treatment on VA campuses, for fear of violent police interactions or legal sanctions that may arise from encounters with VAPD. This concern is especially significant for marginalized veterans, such as veterans of color and disabled or poor veterans. This report shows that the officers' responses frequently conflict with the VA's "commitment to provide the best experience possible to veterans."3

As an organization that exclusively provides support to veterans, the VA aims to address the unique needs of veterans of the U.S. military. The VA’s goal is to provide veterans with “timely and integrated care and support that emphasizes their well-being and independence.”4 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), an organization within the VA, is “America’s largest integrated health care system,” which provides medical care to 9 million veterans each year.5 VHA healthcare facilities offer veterans a variety of essential services, including mental health services, rehabilitation, substance use programs, and treatment for PTSD.6 In particular, disabled veterans rely heavily on VA healthcare.7 Service connected Black, Latinx, Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiian veterans are more likely to rely on VA benefits than are their white counterparts.8 Black veterans with a service-connected disability use the VA healthcare facilities at a higher rate than any other group.9

This report responds to veterans' concerns that policing within VA care centers may hinder access to services and lead to racial profiling and violence against Black, Latinx, disabled, or unhoused veterans. Indeed, as a microcosm of society, the VA is not immune from structural racism, which deeply impacts the lives of former service members. Analysis of VAPD incident reports corroborate media accounts of broad use of police discretion within VA facilities.10

Former service members, their family members, and veterans’ advocates report that VA police officers can create barriers to healthcare, including healthy housing and essential medical care for veterans.

The National Association of Minority Veterans (NAMVETS) and UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic issue this report, with additional contributor Disability Rights California, as the third in a series of publications documenting the VAPD practices. The first was an advisory providing information on the history, role, and scale of the VAPD.11 In November 2021, we published a second report that examined the types of incidents in which the VAPD officers were involved (hereinafter "November 2021 report").12 That report covered VAPD police encounters from the period May 1, 2019, through June 27, 2021.

In this report, we examine police encounters at four VA healthcare system locations: Los Angeles, California; Columbus, Ohio; Tampa, Florida; and Queens, New York (See Table 1 - 2). Our analysis largely follows the same methodology of statistical analysis as the November 2021 report, covering the same locations, but utilizing incidents occurring through September 2022. And unlike the November 2021 report, this report includes a narrative analysis of police encounters.

The inclusion of narrative analysis highlights the effects of police discretion on veterans’ access to medical care. The VAPD features heavily in patients’ healthcare experiences, including throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of healthcare professionals, police are often dispatched to make welfare checks and respond to mental disabilities, behavioral health, or substance use situations. While statistics provide information on the type of incident, the VAPD officer narratives document the myriad ways the police become involved in healthcare as well as the disparate and often violent responses of officers in those situations.

Our narrative analysis shows that the VAPD’s physical contact with patients, as well as heavy policing of the physical spaces and surrounding areas of VA healthcare facilities create an environment inhospitable to veteran care. Unhoused veterans, veterans with a mental health diagnosis, disabled veterans, and veterans of color, especially Black veterans, who are more likely to be perceived as disruptive, are disproportionately affected by policing on VA campuses. Instead of having a safe space to receive medical treatment and just be, veterans are sometimes criminalized and mistreated.

Integrating statistics and narrative, this report illustrates the dire consequences of the heavy policing of VA facilities. As the VA considers the most effective use of VAPD forces and whether policing VA campuses is in the best interest of veterans seeking services, we invite the VA administrators and Congressional representatives to consider the experiences of veterans who have encountered the VAPD while in VA medical care facilities. To that end, this report begins with a discussion of our methodological approach, including a description of the categories of policing incidents under analysis. From there, the report provides substantive analysis of police incidents in three key categories: well-being, spatial control, and inadequately documented. Because this report is part of a series, it also provides a comparison over time as the VA has produced updated incident data. Notably, even with the decline in medical services during the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of policing seems to have remained stable. In short, despite the presence of a pandemic that disproportionately affected the life chances of vulnerable communities, like unhoused veterans and veterans of color, the VAPD continued to impede veteran access to medical care.

1. Methodological Summary

We focus on Tampa, Florida, Los Angeles, California, Queens, New York, and Columbus, Ohio. Table 1-2 presents a breakdown of the numbers of unique patients by race and ethnicity that received health care services at each of the four locations.13 Los Angeles clearly serves the most patients, followed by Tampa, Columbus and then Queens. The population identifying itself as Black or African American represented over 15% of the total at each location, and over 40% in Queens. Those identifying as Hispanic or Latino comprised roughly 16% of the total at Los Angeles but just over 1% In Columbus.14

Number of Unique Patients of Health Care Services at Four Studied VA Locations

The four cities represented in the data are each within one of the top ten states in which veterans are predicted to live by 2030.15

Table 1: Fiscal Year 2021

| VA Category | Los Angeles | Tampa | Queens | Columbus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 89,110 | 103,867 | 8,088 | 40,683 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 45,093 | 73,069 | 2,653 | 29,712 |

| Black or African American | 16,857 | 15,751 | 3,584 | 6,512 |

| Asian | 3,859 | 602 | 234 | 171 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1,143 | 1,235 | 50 | 237 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 914 | 366 | 27 | 175 |

| Multiple/Unknown/Declined to Answer | 21,244 | 12,844 | 1,540 | 3,876 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 58,745 | 83,876 | 6,102 | 36,276 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14,581 | 9,185 | 848 | 549 |

| Unknown/Declined to Answer | 15,784 | 10,806 | 1,138 | 3,858 |

Table 2: Fiscal Year 2023

| VA Category | Los Angeles | Tampa | Queens | Columbus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 89,299 | 112,801 | 6,867 | 44,183 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 45,372 | 78,183 | 1,994 | 31,744 |

| Black or African American | 16,699 | 17,308 | 3,540 | 6,641 |

| Asian | 3,903 | 715 | 227 | 201 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1,224 | 1,266 | 53 | 249 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 945 | 400 | 29 | 185 |

| Multiple/Unknown/Declined to Answer | 21,156 | 14,929 | 1,024 | 5,163 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 57,130 | 88,562 | 5,200 | 38,062 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14,321 | 9,628 | 758 | 591 |

| Unknown/Declined to Answer | 17,848 | 14,611 | 909 | 5,530 |

For each of these locations, the VHA provided police incident data and police reports narrating police encounters pursuant to negotiations following a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request between the federal government and UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic on behalf of the NAMVETS.

Both the Tampa16 and Los Angeles17 VA healthcare systems have more than one facility; the data produced is an aggregate of the reports from all facilities on the respective campuses. The Queens18 and Columbus19 data represent individual hospitals. Thus, the government’s data from Tampa and Los Angeles included thousands of documented incidents while Columbus and Queens each reported less than 800 documented incidents.

The statistical analysis derives from information VAPD officers input into a VHA database. Following each encounter with a person, the officer prepares an "Incident Report" in a database into which they enter one or more "incident types" that are intended to characterize the nature of the incident. Based on the name and language of the incident type, we assigned each incident into one of 18 distinct categories and 73 distinct subcategories. (See Technical Appendix for details, and Appendix A for a complete list of unique incident types that were used in the incidents data along with their assigned categories and subcategories).

For the narrative description analysis, we reviewed a sampling of police documentation including "Incident Reports,” "Use of Force Reports," and "Use of Force Review Memoranda." The Veterans Justice Clinic initially reviewed 79 reports in detail, spanning the four locations. Of those sampled reports, sixty percent are from Los Angeles — the location that serves the most veterans of color. Because of the limited Tampa reports available in the sampling, we reviewed all of Tampa's use of force reports.

There are limitations associated with the analysis of the police reports. The VHA produced heavily redacted police reports, with some reports concealing entire pages. Further, the police reports are one-sided -- only the officer's account, rather than the veteran's, is present. Thus, the one-sided narratives along with the redactions limit the scope of our analysis. A month prior to release of this report, NAMVETS and UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic successfully appealed the redactions. A future report will analyze reproduced unredacted documentation.

In this report, as with the November 2021 report, we focus primarily on three of the top four incident categories and the subcategories within them:20

- Wellbeing

- Spatial Control and

- Inadequately Documented

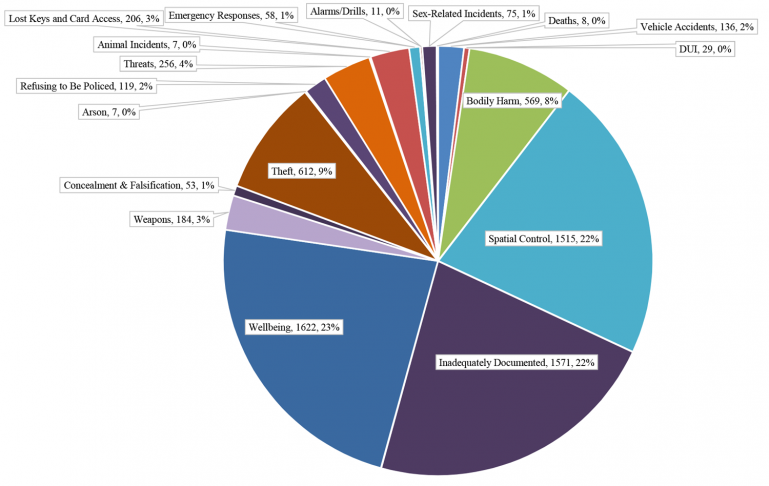

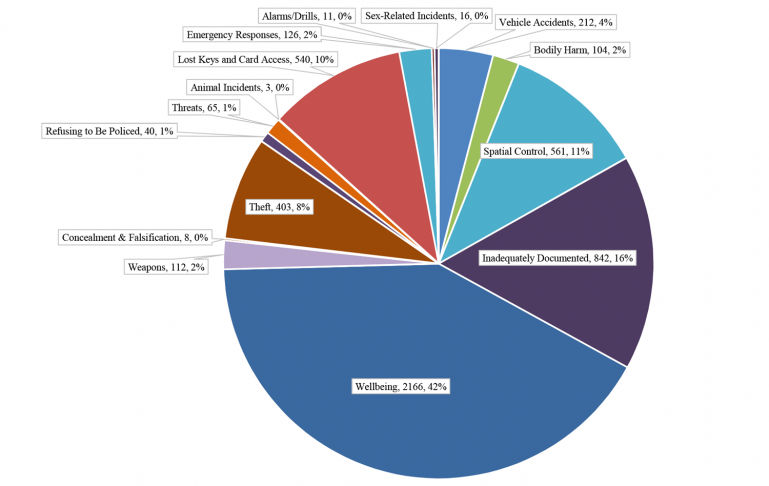

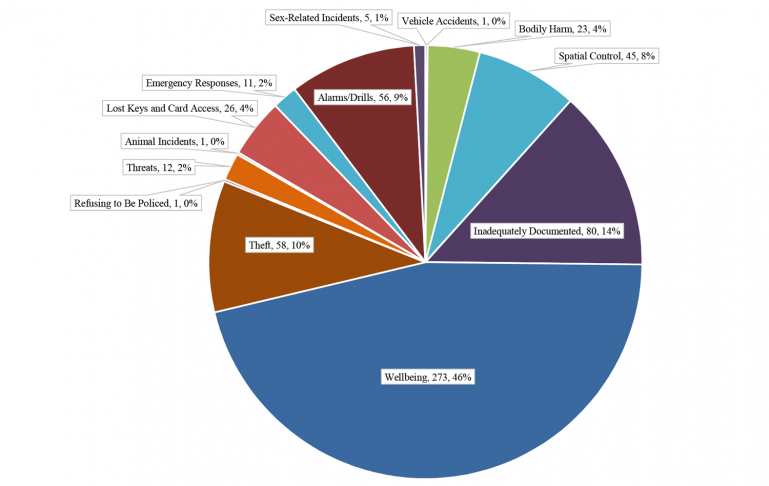

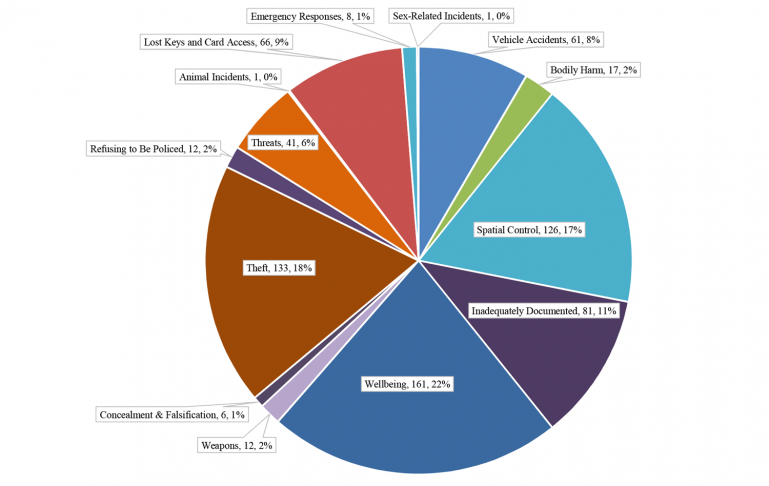

Figures 1.1-1.4 reflect the categorical breakdowns of incidents at each VA location. “Wellbeing” incidents are those that relate to the mental, physical, and emotional health of patients. This category includes behavioral health incidents, where the incident involved a veteran being placed on a mental health hold or where the officer's description of the incident suggests the veteran may be experiencing behavioral health symptoms like suicidal ideation. “Spatial Control” incidents include incidents that relate to policing the VA’s physical facilities and property, including streets and parking lots surrounding VA hospitals.21

The final category reflects incidents with gaps in the data. “Inadequately Documented” incidents include incident types that we cannot accurately categorize based on the incident data. This occurs in two situations. First, some incident types adopt language from a broad federal law or the entire criminal code without further information.22 Consequently, those incidents could potentially fit into multiple descriptive categories if they had been documented with greater specificity. With more complete data entry,23 the number of incidents reported in the substantive categories would be higher. As a result, for narrative reports that fall into the Inadequately Documented category, we analyzed the narratives in the substantive category to which they best correspond. Second, some cases have an incident type that is too vague to allow a reviewer to determine the actual nature of the incident, even at a broad level (e.g., ASSIMILATED CRIMES ACT). These types of incidents were also categorized as Inadequately Documented.24

Even among incident types we did not categorize as Inadequately Documented, distinguishing between Wellbeing versus Spatial Control versus the other categories has challenges beyond the inherently subjective nature of such categories. We more fully address the difficulties of categorization in the "Inadequately Documented" section of this report.

Total Incident Category Breakdowns

Figure 1.1 - Los Angeles

Figure 1.2 - Tampa

Figure 1.3 - Queens

Figure 1.4 - Columbus

2. Wellbeing

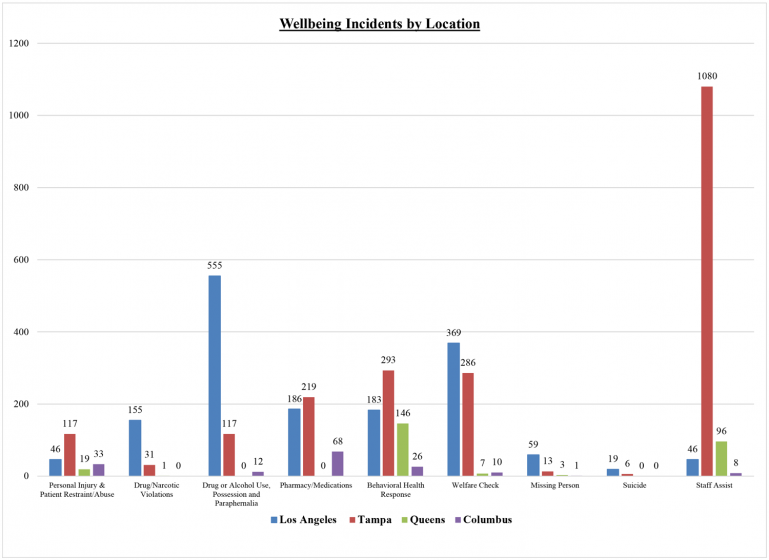

Wellbeing is the largest category of incident reports in most of the locations analyzed.25 The data indicates that the VA gives the VAPD significant responsibility over responding to veterans' health concerns. Out of all documented incidents, Wellbeing represents 46% of incidents in Queens, 42% in Tampa, 23% in Los Angeles, and 22% in Columbus. The subcategories "Welfare Checks" and "Behavioral Health Responses" together make up 34% and 27% of Wellbeing related incidents in Los Angeles and Tampa respectively; and in Queens, Behavioral Health Responses comprise 54% of Wellbeing-related incidents (Figure 2). As Figure 2 shows, across the board, the VA utilizes the VAPD to address patients’ behavioral health. In Tampa, within the Wellbeing category, "Staff Assist" is the largest subcategory (Figure 2), totaling 1,080 incidents, representing 50% of all incidents.26 Although having many fewer total incidents, Staff Assist represents 35% of incidents at Queens.

Drug & Alcohol Related Incidents

Even though the VA recognizes substance use as a health concern, veterans may be met with a police response for drug or alcohol related incidents.27 The VA itself highlights the relationship between substance use and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) diagnoses, noting how veterans with active PTSD symptoms use substances to cope or self-medicate.28 The VA also encourages substance use treatment29 and utilizes a harm reduction approach.30 However, VA policing data suggests that veteran patients attempting to obtain such treatment may find themselves policed at VA hospitals. In Los Angeles, we categorized 555 (34%) Wellbeing incidents in the "Drug and Alcohol Use, Possession, and Paraphernalia" subcategory (Figure 2).31 In Tampa, setting aside the large number of Staff Assist incidents, we categorized 117 or 11% of Wellbeing incidents in the Drug and Alcohol Use, Possession, and Paraphernalia subcategory (Figure 2). The Los Angeles and Tampa VAPD also recorded 155 and 31 incidents, respectively, within the subcategory "Drug/Narcotic Violations" (Figure 2).32

Based on the police reports, examples of VAPD drug and alcohol related incidents include a veteran in possession of methamphetamine,33 a veteran in possession of a small bottle of liquor,34 a veteran who was drunk in public,35 and a veteran whom medical staff suspected of misusing prescription medication.36

A June 2019 interaction between the VAPD and Kyle, a veteran on the West Los Angeles VA campus, provides insight into how the VAPD treats drug-related incidents.37 Officers responded in the “Welcome Center” to a call of a veteran reportedly using drugs in the bathroom. The same building that houses the “Welcome Center,” which the VA describes as "a safe space for Veterans to receive care" and the "first step in the journey out of homelessness" for veterans, has an outpatient methadone clinic for veterans struggling with opiate addiction. Despite this, Kyle was issued a citation for drug possession and trespass. Policing veterans at the Welcome Center for struggling with addiction undermines the Welcome Center’s stated goal.

Welfare Checks

VAPD’s involvement in patient healthcare can take the form of welfare checks. The Tampa facility recorded 286 Welfare Check incidents while the Los Angeles facility reported 369 such incidents (Figure 2). Some of these welfare checks resulted in the veteran receiving citations from VAPD. For example, in March 2019, on the West Los Angeles VA campus, officers observed Lewis, a Black veteran, "walking around in circles talking to himself."38 He “seemed confused and very disoriented, clothes disheveled and very agitated.” The officers initiated a “health and welfare check;” allegedly, they suspected drug use on initial observation. The welfare check quickly escalated to the officers tripping Lewis to the ground, pinning his arm, and leaving him face down on the ground.

What started as a health and welfare check resulted in a forceful encounter and three citations for Lewis.

Although Lewis was ultimately released on the promise that he would seek emergency help for "methamphetamine psychosis," Lewis’ health and wellbeing were not priorities for the officers who instead prioritized policing and punishment.

Mental Health Disabilities and Behavioral Health

Stigma of behavioral and mental health treatment in the military community poses a significant barrier to veterans seeking treatment.39 Mental health disabilities are prevalent among a substantial portion of VHA users, and veterans with mental disabilities face a high risk of houselessness.40 In 2020, 5.2 million veterans experienced a behavioral health condition.41 Upon returning from Afghanistan and Iraq, between 37% and 50% of veterans received a diagnosis for a behavioral health or mental disability, such as PTSD or depression.42 The rate of depression is five times higher in the veteran population than among civilians.43 The VA recognizes the importance of this issue and is committed to providing veterans with comprehensive mental health services.44 Given the prevalence of behavioral health conditions in the veteran community, it is not surprising that VAPD officers often encounter veterans experiencing behavioral health symptoms. VAPD officers in all four locations reported incidents recorded by police as BEHAVIORAL HEALTH RESPONSE incident types. There were 183 incidents under the Behavioral Health Response subcategory recorded in Los Angeles, 293 in Tampa, 146 in Queens, and 26 in Columbus. Instead of aiding veterans in their rehabilitation, VAPD involvement in these situations harmed veterans.

For example, in October 2019, medical staff at the Columbus facility placed Joe on an involuntary mental health hold.45 The medical staff anticipated that Joe may refuse to comply with this hold, so they asked for VAPD assistance. When VAPD officers prevented Joe from leaving, the patient became angry, and police reported he "took a fighting stance." The officers responded to Joe’s resistance with pepper spray, striking his leg four times with their knees, and applying pressure to the nerves in his arm. Ultimately, Joe was tackled by four officers, handcuffed, and medically sedated. He complained of burning in his throat because of the pepper spray used against him. This encounter is an example of how police involvement in involuntary mental health holds can result in physical injury to the veteran and additional mental and emotional distress for patients already experiencing mental health crises.

In addition to the physical and mental toll of policing, VAPD involvement can result in criminalization of veterans experiencing behavioral health symptoms. For example, in March 2020, officers encountered Pete, a homeless veteran, in a staff locker room on the West Los Angeles VA Campus.46 When officers told Pete that he was not allowed in the locker room, he stated that he was there because he was "a CIA agent on a National Security mission." Pete refused to leave the locker room but complied with officers’ commands to place his hands behind his back. After he was handcuffed, Pete was cited for loitering.

The authors are concerned that VAPD encounters may inhibit veterans from seeking medical treatment for their behavioral health conditions because they are afraid of being arrested or cited for exhibiting symptoms on VA property.

Policing Suicide

Suicide prevention within the veteran population is a priority for the VA and Congress.47 Veterans are at disproportionate risk for suicide, with 41% to 61% higher risk than their nonveteran counterparts.48

In 2020, there were an average of 16.8 veteran suicides per day.49 Unfortunately, the VAPD's own documentation reveals that policing mental disability and behavioral health can interfere with a veteran's ability to access life-saving services.

For example, on July 28, 2019, at the West LA VA campus, a Hispanic veteran, Ben, was checking into the hospital around 4:00 a.m.50 Ben was intoxicated and yelling at security guards. When VAPD officers arrived, he accused them of being racist. After he was handcuffed, Ben disclosed to the officers that he wanted to kill himself and had a plan. The officers took him to the emergency department for further treatment but only after issuing Ben two citations that required later court appearances and potential fines. Even if yelling at staff may be inappropriate or disturbing in a healthcare setting, the officers cited a veteran after he disclosed he was suicidal. If seeking help for suicidal ideation leads to police involvement, veterans may be discouraged from seeking assistance at VA facilities when they most need it. The VAPD's conduct in this situation is inconsistent with the VA's mission to prevent veteran suicide.

Pharmacy and Medicine Related Incidents

In some locations, the VAPD engages in many pharmacy-related incidents. In Columbus, the subcategory "Pharmacy/Medications" accounts for the highest number, a full 43%, of Wellbeing incident documentations, and 67 of those (all but one) were categorized as “prescription take backs.”51 The Los Angeles and Tampa facilities reported 186 and 219 incidents, respectively, that we categorized as Pharmacy/Medication (Figure 2). Some of these pharmacy-related incidents included use of force by VAPD.

One particularly egregious pharmacy-related incident in the reviewed sample occurred in November 2019 in Los Angeles.52 Nic, a patient recently discharged from the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center, was sleeping in the waiting room of one of the medical care buildings. When two officers woke him up, Nic informed them that he was waiting for his prescription to be brought to him. One of the officers explained that Nic needed to go downstairs and retrieve the medication himself as well as leave the premises. One officer informed him that “sleeping or loiterer [sic] after-hours with no official business is unauthorized and citable.” Nic did not comply with the officers’ instructions to depart. After pepper spraying the veteran twice for wielding a standard plastic knife (i.e., like the ones commonly distributed at fast food restaurants), the officers escorted Nic to a doctor. As narrated by an officer in the incident report:

I commanded [Nic] to give me the knife and went to grab the plastic knife out of his hand and [Nic] began actively trying to defeat my attempts moving his arms away from me and shouting spray me motherf-----. I heard Officer [redacted name] shout OC and I quickly leaned back out of the spatter area. [Nic] was given commands to drop the knife a few more times, to which he shouted f--- you mother f------ spray me. Officer [redacted name] then conducted a second spray at which point [Nic] started to comply and dropped the knife and laid down prone where handcuffs were applied ensuring proper fit and spacing.

We recognize the VAPD may have viewed Nic’s posturing with a plastic knife while seated as threatening, but we are concerned about the VAPD officer’s disproportionately violent response of using two rounds of pepper spray. The officer’s account suggests he interpreted Nic’s verbal response as an invitation to enact violence. In our view, this was an inappropriate act of violence and exercise of discretion, and this serves as an example of VAPD hindering veteran access to medications needed upon hospital discharge.

Figure 2

Similarly, in Tampa, VAPD used force against a veteran, Sam, in an incident related to medicine access. In a memorandum investigating VAPD’s use of force during the encounter, a Deputy Chief of Police discussed two separate encounters with Sam.53 The first incident occurred on September 2, 2015. As told by the Deputy Chief, Sam was “acting disorderly" and "a lynx panic alarm was activated." Sam was upset because he thought he was not getting the medication that he needed. After the VAPD officer calmed Sam down, the officer escorted him to the Emergency Room where Sam was "given a warning about his conduct.”

The second report was written on February 24, 2016. An officer observed Sam yelling at VA staff and asked Sam to calm down. Sam continued to yell at staff and told the officer to "F--- Off.” In response, the officer called for backup and another officer arrived. Sam pushed one of the officers and “at that point he was taken to the ground.” Sam began having a seizure, which the officer characterized as “hitting his head up and down on the floor while kicking his legs and feet.” He was immediately taken to the emergency department and was treated for his seizure. Sam was cited for disorderly conduct.

In the first incident, Sam told VA medical staff that he did not have the proper medicine, and their response was to initiate a VAPD encounter. A few months later, Sam had a seizure during a second VAPD encounter. The authors are concerned that there may be a relationship between Sam’s advocacy about the deficiency in his medication and his seizure several months later. The VAPD was called into a situation where a veteran was self-advocating in a medical space designed for veterans, and this interference from the VAPD may have served as an obstacle to Sam receiving necessary preventative care to avoid his subsequent seizure.

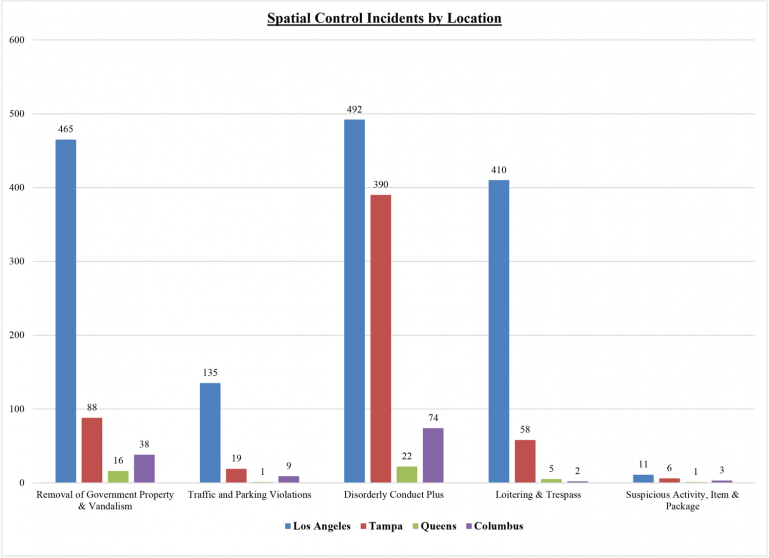

3. Spatial Control

The VHA data suggests that one of the VAPD’s primary roles is maintaining strict control of healthcare spaces.

In all locations except Queens, Spatial Control is among the top three categories of incidents documented by the VAPD. Roughly one fifth of incidents in Los Angeles (22%) fall within the Spatial Control category. In Columbus, 17% of incidents fall within the Spatial Control category and 11% of incidents in Tampa. In Queens, where the Spatial Control category is fifth-most frequent, it comprises 8% of incidents. In Columbus, the subcategories, "Disorderly Conduct Plus" and "Removal of Government Property & Vandalism," account for 89% of all Spatial Control incidents (Figure 3). In the Greater Los Angeles healthcare system, this combination accounts for 63% of total incidents, 85% for Tampa, and 84% for Queens. In Los Angeles, the subcategory "Loitering and Trespass" accounts for an additional 27% of Spatial Control incidents (Figure 3). In Los Angeles, 292 of Loitering and Trespass incidents (19% of the Spatial Control category) are incident types described as unauthorized loitering or sleeping.54 Examples include an unhoused male cited for sleeping on the side of a building55 and a woman nonveteran cited and released for sleeping on VA property.56

Loitering/Trespass

The Loitering and Trespass incident types are particularly troublesome because of the large number of veterans comprising the unhoused population and, as evidenced from incident reports, unhoused veterans' use of VA spaces. Collating data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress and the 2022 U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates, the National Alliance to End Homeless found that as of 2022: 3,456 unhoused veterans live in Los Angeles (10,395 unhoused veterans in California); 482 unhoused veterans live in New York City (990 unhoused veterans in New York), 91 unhoused veterans live in Columbus (633 unhoused veterans in Ohio), and 147 unhoused veterans live in Tampa (2279 unhoused veterans in Florida). These numbers are conservative estimates.57

The federal government has recognized that veterans are particularly vulnerable to houselessness.58 Criminalizing veterans for their occupying of VA property misaligns with the mission of the VA and the purpose of its medical centers to aid veterans in need.

The VAPD often criminalizes veterans who use VA medical services by issuing citations for loitering, trespass, and/or disorderly conduct. For example, on August 19, 2019 at 10:23 pm, a Los Angeles VAPD officer stopped Chris, a veteran wearing “red patient pajamas” but no shirt, at a VA campus bus stop while the officer was on vehicle patrol.59 The officer asked Chris “what he was doing on [VA] property at this hour and what had happened to his face;” Chris had moderate facial swelling around his right eye. Chris replied that he had fallen asleep, awoken with the swelling, and at the moment, he was simply “relaxing.” The officer then had dispatch run a warrants check. Chris had a misdemeanor warrant for trespassing. The Santa Monica Police Department was unwilling to pick Chris up so the officer received confirmation that Chris could be booked at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Reception Center. Chris attempted to flee but was ultimately arrested and taken to booking for the trespassing warrant.

Despite wearing clothing that indicated that Chris was using or had likely used VA medical services recently (“red patient pajamas”), the officer arrested Chris. This is an example of how the VAPD’s common use of warrant checks after stopping individuals for loitering contributes to the criminalization of veterans. The NAMVETS, DRC, and Veterans Legal Clinic are concerned about this implication since vulnerable veterans may be disproportionately affected.

Disorderly Conduct Plus

Disorderly Conduct Plus60 as a subcategory is documented across all four campuses. Incident types categorized as Disorderly Conduct Plus include incident types involving excessive noise, obstruction of the "normal operation" of services, or improper disposal on the property.61 These incidents require the officer to exercise discretion in determining whether behavior is “disorderly.” In Queens, 19 out of the 22 incidents included in the Disorderly Conduct Plus subcategory involved failing to comply with restrictive signage.62 In Columbus, 74 incidents in the Spatial Control category were for incidents within the subcategory Disorderly Conduct Plus and 38 incidents were documented for Removal of Government Property & Vandalism. Los Angeles and Tampa have the most Disorderly Conduct Plus incidents: 492 and 390, respectively (Figure 3). In Tampa, citations with charges for disorderly conduct sometimes involve patients who attempt to leave VA health facilities but cannot due to the Baker Act, a statute that enables medical professionals to keep patients involuntarily through a medical hold. Examples include use of force against a Baker Act patient who refused to take prescribed medication and tried to leave,63 use of force against a patient who stripped naked and took fighting stance in protest to being placed on a Baker Act hold,64 and use of force against a patient who refused to be transported to an outside facility and displayed passive resistance to medical personnel’s administration of medicine.65

One of the more notable VAPD use of force reports illustrate the steps to initially coerce and then legally require a patient to remain in VA care.66 As described in the incident report:

On October 22. 2016 at 8:27 a.m., Officer [redacted name] was posted in the [redacted location] when RN [redacted name] reported that patient [Clara] wanted to leave. He was advised that she was not a Baker act patient. He was able to get her back to her room so he could talk to her in private. After a few minutes, she decided that she wanted to leave and started toward the door. At this time, the Doctor had placed her under a Baker Act and she was not free to leave. Officer [redacted name] and [redacted name] grabbed her arms in an attempt to escort her back to the room. While walking her back to the room, their feet got tangled up and they fell to the ground. Officers [redacted name] and [redacted name] placed her arms in a wrist lock and [redacted name] was able to get her handcuffed…She was placed on a stretcher and taken back to her room.

In this incident, VA medical staff called in VAPD to pseudo-detain a patient who the VA did not have a legal right to detain. As stated in the incident report, Clara “was not a Baker [A]ct patient” when she attempted to leave VA facilities. It was only after the officer was unable to convince Clara to stay voluntarily and Clara attempted to exercise her right to leave that VA medical staff placed Clara under a Baker Act hold. It is unclear from the report what disturbance Clara caused besides exercising her right to leave and why VA personnel involved VAPD. This appears to be a situation where VAPD were involved in patient care (or refusal of care in this case) due to the exercise of patient’s right to leave. The authors are concerned that VA medical staff may have inappropriately used the VAPD to coerce Clara into staying at the VA or to delay Clara long enough that a Baker hold could be processed.

Another poignant example of VAPD-veteran engagement in VA medical facilities is documented in an April 2019 Los Angeles use of force form.67 In this incident, a VAPD officer forcibly removed an elderly male veteran from a medical services building. As documented in the form:

I contacted [Ross] at this wheelchair he was seated on, although [Ross] can walk without a problem he constantly is given wheelchairs for his use. [Ross] ignored me calling out his name; he did not open his eyes and did not answer my commands to wake up. [Ross] pretended to sleep and ignored my commands; after several attempts ordering him to depart, I decided to assist rolling the wheelchair out, with [Ross] on it, because I knew, from tens of past instances, [Ross] did not have legitimate business on campus.”

Then, as the officer approached Ross, the veteran stood up, cursed at the officer, and said “I am not going anywhere. I am hurting. I need to use the bathroom motherf-----.” The VAPD officer presumed, based on previous interactions, that the veteran did not have a legitimate purpose for being at the VA medical facility on this occasion.

This veteran may have been unhoused with nowhere else to be, seeking respite among other veterans.

The officer also suggested that the veteran did not need a wheelchair simply because he can “walk without a problem.” Such a statement indicates a lack of awareness about disability generally.

The officer appears to be unaware that many wheelchair users can walk some of the time, or use wheelchairs to manage chronic pain, joint pain, fatigue, seizures, fainting, or other medical needs. Here, the officer’s assumptions hindered Ross’ access to toileting facilities merely out of annoyance based on the officer's assumption that that the veteran did not need to use a wheelchair. Presuming disability fraud should not be accepted within the VA. According to his investigation narrative, this officer commanded the veteran to leave the VA campus. After the veteran refused, the officer attempted to arrest him for refusing to leave. The veteran was “defiant and still wanted to enter the building,” presumably to use the bathroom. The officer called for backup and the veteran was taken to the ground on his stomach and handcuffed with the assistance of other officers

Table 3: Inadequately Documented Incidents

| Subcategory | Los Angeles | Tampa | Queens | Columbus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Report Only | 366 | 517 | 63 | 40 | 986 |

| Assimilated Crimes Act | 540 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 553 |

| Joint Law Enforcement | 323 | 157 | 1 | 27 | 508 |

| Inadequately Documented | 86 | 91 | 8 | 1 | 186 |

| Assessments | 76 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 91 |

| Federal | 69 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 79 |

| No Incident Type | 68 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 74 |

| Policy Violation | 30 | 33 | 4 | 3 | 70 |

| Incidents: Other Offenses | 13 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 23 |

| Report of Survey | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 1,571 | 842 | 80 | 81 | 2,574 |

Figure 3

4. Inadequately Documented

The VAPD inadequately documents a sizable portion of incidents in its incident record keeping system. In Los Angeles, the Inadequately Documented category is the second largest category (Figure 1.1). Across all three locations, this category makes up between 11% and 22% of the recorded incidents (Figures 1.1 – 1.4). Some VAPD data entries lack any information whatsoever. For example, Los Angeles VAPD reported 68 incidents whose incident type was “No Incident Type” (Table 3).

With the Inadequately Documented category, incident types suggest unspecified information gathering (classified in the subcategory Information Report Only)68 and are recorded frequently in all four locations.

Systematic acceptance of such record keeping practices allows police to misuse their broad police discretion. Where police are responsible for recording their actions, and the recording practices create an opaque understanding of police work, misconduct may fester and grow.

These incident types require reviewing the reports individually to understand the nature of the VAPD interaction. Tampa reported 517 of these incidents (61% of Inadequately Documented); Los Angeles reported 366 (23%); Columbus reported 40 (49%); and Queens reported 63 (79%) (Table 3).

As noted above, there are challenges to categorizing incidents in both the Inadequately Documented category, as well as incidents we placed in other categories. These challenges affect distribution outcomes and affect the accuracy of comparing across facilities. First, the police at various locations may interpret the meanings of the incident types differently or apply them differently and may choose to use one in place of another. Second, there are incident types that are in substance quite general even though they initially appear to fall into one of the categories determined to be adequately documented.

Consider, for example, the much larger proportion of incidents that are categorized as Wellbeing at Tampa compared with the other locations. As shown in Figure 2, and highlighted above, this appears to be driven by a disproportionate use of incident types grouped into the Staff Assist subcategory. This also appears to be true at Queens, though the total number of incidents is much smaller than at Tampa. Officers at the Tampa location used these incident types for 1,080 out of 5,209 incidents (21% of the time), whereas officers at the Los Angeles location, which had 35% more incidents, used these incident types only 46 times out of 7,038 Incident (less than 1% of the time). While this may accurately reflect actions attributable to a patient's or visitor’s wellbeing, the inflation to the Wellbeing category suggests that the description in the data is too general to be very meaningful, while being too readily used by VAPD officers, at least at Tampa.

Inadequately Documented - Joint Law Enforcement

In the three and a half-year period we analyzed, 323 and 157 Joint Law Enforcement incidents were inadequately documented in Los Angeles and Tampa, respectively (Table 3). In Columbus, there were 27 such incidents, or a full 33% of their Inadequately Documented incidents. This shows that the VAPD, particularly in these areas, work alongside law enforcement agencies to respond to incidents on VA campuses and in the community. "Joint Law Enforcement" incidents include encounters where VAPD assist the local police to enforce outstanding warrants. In our review of VAPD documents, VA police in Tampa and Los Angeles proactively check national and state criminal justice databases during their interactions with veterans.69 If these checks reveal that the veteran has an outstanding arrest warrant70 from an outside law enforcement agency (sheriff's department, local police department, etc.), VAPD may contact the outside law enforcement agency to coordinate the arrest of the veteran. For example, in February 2020, Pat was sleeping on the Los Angeles VA campus.71 The VAPD ran a warrant check and learned that Pat had an outstanding warrant so they called the Los Angeles Police Department to pick up Pat. Similarly, VAPD officers in the Columbus facility released Larry to a Franklin County Sherriff Deputy for an outstanding warrant after he was seen urinating in public in April 2019.72 The current practice of searching for outstanding warrants, and subsequently enforcing them, may deter veterans, and poor veterans who may be unable to make bail in particular, from seeking healthcare services.

If a veteran knows he has an outstanding warrant, the fear of arrest may lead to a delay seeking healthcare services from VA facilities. This delay could have a detrimental impact on the health of the veteran.

These examples of Joint Law Enforcement incidents further illustrate how the VA discourages unhoused veterans from being on VA property. A veteran sleeping or urinating in public might be unhoused and could have nowhere else to go. Releasing veterans in these circumstances to outside law enforcement agencies is an inadequate way to deal with unhoused veterans. As discussed in the Spatial Control section, the VA cannot fulfill its commitment to supporting unhoused veterans if it criminalizes veterans occupying VA property.

5. Remaining Categories

This report focuses on the leading incident types across four VA healthcare locations. All other incident types, when combined, make up roughly 49% of incidents documented in Columbus; 31% in Tampa; 33% in Los Angeles, and; 33% in Queens (Figures 1.1 – 1.4).73 In Columbus, the remaining most frequent categories are "Theft" (18%), "Vehicle Accidents" (8%), and "Lost Keys and Access Cards" (9%). In Queens, they include Theft (10%) and "Alarms/Drills" (9%).

As seen in Figures 1.1 to 1.4, Theft accounts for between 8% and 10% of all incidents in Los Angeles, Tampa, and Queens, but a full 18% in Columbus. In these four locations, the subcategory “Missing Property” within the Theft category makes up between 21% and 41% of these incidents and is the highest subcategory of Theft-related incidents in Tampa. Based on redacted incident reports and qualitative information, the authors suspect Columbus’ considerable number of theft incidents may be explained by the presence of a gift shop within its Chalmers P. Wiley Veterans Outpatient Clinic.

Incidents within the "Bodily Harm" category account for only 2% at Columbus and Tampa, 4% at Queens, and 8% of incidents at Los Angeles.74 Many of these incidents are simple assaults or batteries.75 The category "Threats," which includes the incident types indicating harassment, terrorist threats, non-violent physical threat, and stalking, accounts for between 1% and 6% of incidents across all four locations. The Weapons category represents 2% of incidents reported in Tampa, and Columbus, and 3% in Los Angeles (none at Queens).

6. Trends Since the November 2021 Analysis

Not surprisingly, given the substantial temporal overlap, we find similar distributions of incidents compared to those in the November 2021 report findings. Wellbeing incidents comprise roughly 23% at Los Angeles, 42% at Tampa, 46% at Queens, and 22% at Columbus over the 40 months covered by this report. These are similar to the proportions reported in the November 2021 report: 24%, 40%, 48%, and 22%, respectively. Spatial Control incidents comprise roughly 22% at Los Angeles, 11% at Tampa, 8% at Queens, and 17% at Columbus. These are also similar to the proportions reported in the November 2021 report: 20%, 11%, 8%, and 18%, respectively.76

We investigated the change in the distribution profile of the types of incidents between those presented in the November 2021 analysis (which used incidents occurring through June 2021) and additional incidents presented in the current analysis (which uses incidents occurring through September 2022).

Broadly, the same incident type categories dominate in both the earlier and later periods. When we consider the category percentages derived from only the incident reports occurring since June 27, 2021, the last incident report date from the November 2021 report, we continue to find that Wellbeing, Spatial Control, and Inadequately Documented are among the largest categories.77 As we describe in more detail below, the proportion of incidents identified as Inadequately Documented has declined somewhat: it does appear that the VAPD is improving how they document police interactions, although there remains substantial room for improvement.

Wellbeing

Generally, the subcategories that dominated the distributions of Wellbeing incidents within each of the four locations in the November 2021 report remained the top subcategories in the later period.

We observe, however, a notable frequency shift in Tampa and Queens between Staff Assist and Behavioral Health Response incidents that quite possibly reflects a change in police recording in the period covered by the November 2021 report and the later period, as opposed to a qualitative change in the nature of the incident. A relative reduction in Staff Assist incidents seems offset by increases in the share of Behavioral Health Response incidents at both Tampa and Queens. As highlighted above (and see Figure 2), Staff Assist incidents at these locations (over the entire period) comprise a large proportion of total Wellbeing incidents. We understand the Staff Assist incident type to include police involvement when care staff requests help in managing a patient in crisis.

Spatial Control

Generally, the subcategories that dominated the distributions of Spatial Control incidents within each of the four locations in the November 2021 report remained the top subcategories in the later period. In particular, the distributions across subcategories for Los Angeles and Tampa look very similar in the period shown in the November 2021 report compared to the later period.

The most notable changes are in the frequencies at Queens and Columbus. However, these are the locations with the fewest incidents in the Spatial Control category (only 45 at Queens and 126 at Columbus over the entire period analyzed), so even a small shift in the number of incidents between subcategories will show up as large changes in the frequency percentages. Thus, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about meaningful changes in policing within this category.

Inadequately Documented

Generally, the subcategories that dominated the distributions of Inadequately Documented incidents within each of the four locations in the November 2021 report remained the top subcategories in the later period. However, the most notable change has been a decline in the proportion of incidents with an incident type recorded in the data as "No Incident Type," where the decline has occurred in every location.

In Los Angeles, 27% of incidents were determined to be of the category Inadequately Documented in the November 2021 report versus only 22% in the current updated analysis. For Tampa and Columbus, these percentages, respectively, are 19% versus 16%, and 13% versus 11%. For Queens, the percentage is unchanged at 14%. This is an indication that the VAPD has been improving their incident type recording practices.

We recommend that the VA continue to improve their data keeping policies and practices to further reduce the number of inadequately documented police incident reports.

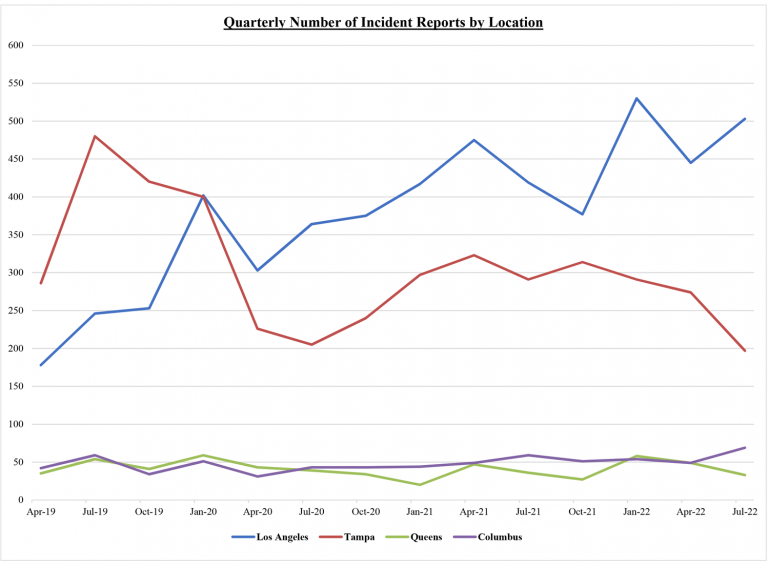

7. COVID-19 and Results

Figure 4

Figure 4 shows the quarterly number of recorded encounters resulting in the creation of an Incident Report by location.78 The number of encounters in Los Angeles has increased over the period analyzed. This may be due to the fact the during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of veterans residing on the premises increased. In contrast, the number of encounters in Tampa declined substantially right at the beginning of the pandemic in the first quarter of 2020. This is likely consistent with reduced services at the VA during this period.

Conclusion & Recommendations

From its involvement in veterans' healthcare to its policing of the VA’s physical spaces, the VAPD is inappropriately enmeshed in many aspects of a veteran's experience on a VA campus. This report has shown that the officers' responses frequently conflict with the VA's "commitment to provide the best experience possible to veterans."79 The statistical and narrative data in this report demonstrate how VAPD officers’ use of discretion and over-involvement in VA healthcare lead to violent interactions with veterans. This does not uphold the VA's goal of being "truly veteran-centric."80

To fulfill its promise "to care for those who have served in our nation’s military," the VA must evaluate its relationship with the VAPD.81 The VAPD practices detailed in this report may deter veterans from seeking treatment through the VA. This concern is especially significant for marginalized veterans, such as veterans of color and disabled or poor veterans.

As the VA considers how to address the problems we highlight with the VAPD, we recommend the VA take the following steps to more effectively serve and protect veterans:

- Remove VAPD from behavioral health and welfare checks; instead, utilize staff and veteran peers adequately trained to respond to behavioral health and welfare checks. Allow veterans to have a role in shaping new conceptions of wellbeing and healthy spaces within the VHA that do not need police or security.

- Train and hire adequate numbers of veteran peer workers, healthcare workers, and social workers to respond to the unique needs of former service members in distress or crisis.

- Investigate whether the VAPD disproportionately polices marginalized and medically vulnerable patients. In particular, examine policing for encounters involving loitering, trespass, resisting, and disorderly conduct. Ensure any audits or investigations consider intersectional and multiple identity categories (e.g. race, houselessness, and/or disability).

- Require VAPD officers to complete comprehensive cultural competency training on a regular basis.

- Research the impact of VAPD on patients’ access to healthcare and healthcare experiences (e.g., increased stress, re-traumatization).

- Facilitate more accurate data collection and record keeping.

- Ensure VA services are accessible to veterans, so they are not deterred from seeking treatment out of fear of VA police interactions.

Acknowledgements

The primary authors of this report are Claire Canestrino (‘25) and Kimberly Chantal Welch (‘25), law students representing NAMVETS as part of the Fall 2023 UCLA Veterans Justice Clinic. They worked under the supervision of Sunita Patel, an Assistant Professor of Law at the UCLA School of Law where she serves as the Faculty Director of the UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic. We acknowledge the work of other UCLA Veterans Justice Clinic students from Fall 2019, Spring 2020, Fall 2021, and Fall 2022 who drafted and submitted the FOIA request, wrote previous reports, and filed administrative appeals. Without the earlier efforts, this report would not be possible. Thank you Jasmine Buckley, Emily Olivencia-Audet, Maya Chaudhuri, Will Ostrander, Jess Johnson, Charlie Pollard-Durodola, Rachel Long, and Ian Anstee. We acknowledge Aisha Novasky for her ongoing role partnering with the clinic on this report and in obtaining its underlying data. She is a Senior Attorney in the Civil Rights Practice Group at Disability Rights California, where she focuses on the intersection of people with disabilities and their disproportionate interactions with law enforcement.

-

The National Association of Minority Veterans (NAMVETS) of America is a not-for-profit veteran’s service organization that serves America's 5.5 million veterans of color in communities across the United States. Since 1969, NAMVETS of America members have advocated for veterans, ensuring they have full access to information and resources they need to not only improve the quality of their lives but also improve the conditions of the communities in which they live. More information about the National Association of Minority Veterans of America is available on its website: https://www.namvetsamerica.org/.

-

The UCLA School of Law's Veterans Legal Clinic has a dual teaching and legal services mission. Law students assist veterans in Los Angeles while developing lawyering skills under the supervision of the clinic's faculty. The clinic is housed at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs West Los Angeles campus. The clinic primarily represents former service members who are chronically homeless and those who are disabled and returning from incarceration. More information about the UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic is available on the clinic’s website: https://law.ucla.edu/academics/experiential-education/clinics/veterans-legal-clinic/.

- Disability Rights California (DRC) is the largest disability rights organization in the country and is the agency designated under federal law to protect and advocate for the rights of Californians with disabilities. Disability Rights California specializes in disability discrimination law, including the Americans with Disabilities Act and Fair Housing Amendments Act, and they litigate complex discrimination cases statewide. More information about Disability Rights California is available on its website: https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/.

We thank Mark Rodini, Bret Dickey, and Adam Vogel with Compass Lexecon for their invaluable contributions to the statistical analysis and written descriptions provided within this report. We also thank Gerloni Cotton, Lecturer in Law at the UCLA School of Law, Jeanne Nishimoto, Associate Director of the UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic, and Navneet Grewal, Litigation Counsel of DRC, for their thoughtful reviews and suggestions. We appreciate the discussions and comments from student colleagues in the Veterans Justice Clinic Fall 2023 seminar.

We especially thank Horace Walker Jr., National Director for Claims for NAMVETS, for his vision, insightful comments, and guidance. We acknowledge the former service members, families, and communities affected by the structures of policing and health inequality, and the healthcare providers who aim to improve the lives of their veteran patients.

The presentation, findings, and recommendations of this report are the work of the NAMVETS, DRC, and UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic. They do not represent official positions of the UCLA School of Law or the university.

- 1. Dep’t Veterans Affs., Off. Inspector Gen., No. 19-05798-107, VA Police Information Management System Needs Improvement 29 (2020), Connor Brooks, Bureau of Just. Stat., NCJ 304752, Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 2020 – Statistical Tables 4-5 tbl.1 (rev. 2023). See also Open the Books, The Militarization of the U.S. Executive Agencies: Non-military Purchases of Guns, Ammunition, and Military-Style Equipment FY 2015-2019, at 16-19 (2020). Recent budget requests include an increase for police personnel, and multiple Congressional hearings in the last few years suggest Congress may appropriate enough for the VA to continue substantial expansion of its police operations. See Dep’t of Veterans Affairs, FY 2024 Budget Submission: Vol. 3 Benefits and Burial Programs and Departmental Administration 358 (2023) (budget request for five FTE ($1.2 million) by the Office of Security and Law Enforcement (OSLE) “to enhance the Department’s oversight mission of VA’s police force to include its services, inspections, criminal oversight, and investigations.”); Dep’t of Veterans Affairs, FY 2022 Budget Submission: Vol. 3 Benefits and Burial Programs and Departmental Administration 352 (2021) (budget request for the Office of the Chief of Police); Dep’t of Veterans Affairs, FY 2021 Budget Submission: Vol. 3 Benefits and Burial Programs and Departmental Administration 339-40 (2020) (budget request for twenty-four FTE ($5 million) by the Office of Police Modernization “to realign VA’s police force”); Modernizing the VA Police Force: Ensuring Accountability: Hearing Before the H. Subcomm. on Oversight and Investigations of the H. Comm. on Veterans’ Affs., 117th Cong. (2021) (statement of Leigh Ann Searight, Deputy Assistant Inspector General).

- 2. See, e.g., Thao Nguyen, DOJ Says Veterans Affairs Police Officer Struck Man with Baton 45 Times at Medical Center, USA Today (Oct. 4, 2023, 12:35 AM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/10/04/veterans-affairs-police-officer-baton-justice-department/71050964007/; Former Officer Charged with Excessive Force at Hospital, AP (Oct. 2, 2019, 3:51 PM), https://apnews.com/general-news-1e523274fa394b60b9ee33cddea7ed2a.

- 3. 38 C.F.R. § 0.600.

- 4. U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., FY 2018 - 2024 Strategic Plan 13 (2019).

- 5. Veterans Health Administration, U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. (last updated Dec. 5, 2023), https://www.va.gov/health/.

- 6. Health Topics A to Z Index, U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. (last updated Jan. 22, 2015), https://www.va.gov/health/topics/index.asp.

- 7. The National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics (NCVAS) conducted a study on veterans who have used at least one of 22 benefits or services provided by the VA during Fiscal Years 2008 through 2017. The analysis included a comparison by various characteristics to Veterans who did not use any VA benefits. Veterans who used at least one benefit or service are termed ‘users’ and Veterans who did not are termed ‘non-users.’ The overall use rate of the VHA among veterans with a service-connected disability is 69.6%. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, VA Utilization Profile FY 2017, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs. (May 2020), https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/VA_Utilization_Profile_2017.pdf.

- 8. Service-connected FY 2021 data indicates 79.1% of Black veterans, 72.1% of Latinx veterans, 70.9% of American Indian/Alaskan-Native veterans, 69.1% of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander veterans, 68.8% of White veterans, and 65.1% of Asian veterans used VA Health Care. U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., Percentage of Service-Connected Disabled Veterans Who Used VA Health Care, by Race/Ethnicity, FY 2021.

- 9. Id.

- 10. See, e.g., Jasper Craven, Abusing Those Who Served, The Intercept (July 8, 2019), https://theintercept.com/2019/07/08/veterans-affairs-police-va/; Matt Agorist, Video: Cops Attack Elderly Vietnam Vet at Hospital Over Misunderstanding at Metal Detector, The Free Thought Project (May 30, 2016), https://thefreethoughtproject.com/video-cops-attack-elderly-vietnam-vet-hospital-misunderstanding-metal-detector/; Andy Marso, Veteran Died After KC VA Police Officer Injured Him During Traffic Stop, The Kansas City Star (last updated Dec. 14, 2018, 7:57 PM), https://www.kansascity.com/news/business/health-care/article223129870.html.

- 11. Sunita Patel, Maya Chaudhuri & Will Ostrander, National Association of Minority Veterans (NAMVETS) and UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic Advisory: The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Police Force (2020).

- 12. Policing Veterans: An Analysis of Veterans Affairs Police Department `Incidents,', UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic and National Association of Minority Veterans of America (NAMVETS), November, 2021.

- 13. These data were provided by the VHA In Excel files "Copy of FOIA 22-00786-F_additional data (002).xlsx" and "FOIA 23-00234-F redacted.xlsx". The data include inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy care, and for Fiscal Year 2022, also include "Non-VA care." As the data was provided, Race and Ethnicity appear to be distinct VHA categorizations in that one cannot be derived from the other.

- 14. This report uses the terminology “Hispanic” to reflect the way the VHA categorizes race and ethnicity data.

- 15. U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., FY 2018 - 2024 Strategic Plan 43 (2019).

- 16. The VHA produced spreadsheets documenting police activity for Tampa’s VA healthcare facilities. See VA Tampa Health Care Locations, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., https://www.va.gov/central-ohio-health-care/locations/chalmers-p-wylie-veterans-outpatient-clinic/ (last accessed Dec. 10, 2023) (listing facilities within the Tampa healthcare system).

- 17. The VHA produced spreadsheets documenting police activity for Greater Los Angeles’ VA healthcare facilities. See VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care Locations, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., https://www.losangeles.va.gov/locations/index.asp (last accessed Mar. 4, 2024) (listing facilities within the Greater Los Angeles healthcare system).

- 18. See St. Albans Medical Center, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., https://www.va.gov/find-locations/facility/vha_630A5 (last accessed Dec. 10, 2023).

- 19. See Chalmers P. Wylie Veterans Outpatient Clinic, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., https://www.va.gov/directory/guide/facility.asp?id=34 (last accessed Dec. 10, 2023).

- 20. Queens is the exception, where incidents of Theft (10%) and Alarms/Drills (9%) are more frequent than Spatial Control (8%).

- 21. Spatial Control includes the subcategory "Traffic and Parking Violations" because of how traffic and parking offenses have been used to target the houseless persons in other police contexts. The authors’ categorization separates traffic and parking incident types from those found in the categories Vehicle Accidents and DUI to capture traffic infractions that involved drugs or alcohol separately.

- 22. In some instances, a regulation or law is cited but the regulation or law encompasses numerous activities that may fall in different subcategories. For example, the incident type FEDERAL : CFR : 38 CFR 1.218(B) refers to 38 C.F.R. 1.218(b) which punishes a lengthy list of conduct, including gambling, unlawfully consuming alcohol, or possession of a firearm. Incident types sometimes include additional detail for each of these actions (e.g., FEDERAL : CFR : 38 CFR 1.218(B) : (17) UNAUTHORIZED USE ON PROPERTY OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES OR NARCOTIC DRUGS-HALLUCINOGENS-MARIJUANA-BARBITURATES OR AMPHETAMINES), and we have included the known incident types among the appropriate categorizations. Other incident types cite to the entirety of a large federal law, such as the incident type “ASSIMILATED CRIMES ACT.”

- 23. While there is a correspondence between the Incident Reports recorded in the VHA database and the Incident Reports from which detailed narrative descriptions are found, matched through common Incident Report Reference Numbers, the information that is easily extractable from the database generally lacks more detailed information related to the incidents analyzed within this report. Therefore, gaining a clearer picture of a police encounter requires individually reviewing the original incident reports.

- 24. For the remainder of this report, the names of incident type categories and subcategories we created for the purposes of the analyses are surrounded in quotes the first time the name is used but are not In quotes thereafter. In cases where the literal text (or a short extract of the text) from an incident type as it is recorded in the VAPD data is given, this will appear in all capital letters, as it appears in the data.

- 25. In the November 2021 report, Wellbeing was the second-largest category after Inadequately Documented.

- 26. Based on a combination of direct knowledge from health providers and the role of police in institutional contexts, the authors understand Staff Assist incident type to include police involvement in circumstances where a patient or visitor is disruptive or rude, or to support the needs of care staff when managing a patient in crisis.

- 27. Mental Health, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/ (last accessed Dec. 5, 2023).

- 28. PTSD and Substance Use in Veterans, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs., https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/related/substance_abuse_vet.asp (last accessed Dec. 5, 2023).

- 29. Id.

- 30. Any Positive Change: VA Saving Lives with Syringe Service Program, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs. (Aug. 30, 2022), https://www.va.gov/illiana-health-care/stories/any-positive-change-va-saving-lives-with-syringe-service-program/ ("Harm reduction supports people no matter where they are in the spectrum of drug use, ranging from chaotic to abstinence-based recovery. ").

- 31. The unusual number of incidents in the Greater Los Angeles Healthcare system data may be driven by the fact that people reside on the West LA VA campus.

- 32. Our subcategory "Drug/Narcotic Violations" includes incident types that indicate generally the type of perpetrator (BY PATIENT, BY VISITOR, BY EMPLOYEE/STAFF) and often indicate more specifically that it is a DRUG/NARCOTIC EQUIPMENT VIOLATION. However, beyond that, it is impossible to determine with certainty whether these violations are for drug use, possession, manufacture, or sale. In actuality, the number of incidents in the Drug and Alcohol Use, Possession and Paraphernalia subcategory could be much higher if in the language of the incident type was more specific. Even if we presume all such incidents are related to sale, the change is exceedingly small in the Wellbeing category. Removing Drug and Narcotic Violations in Los Angeles would result in a decrease of 155 incidents in the Wellbeing category. In Los Angeles, Wellbeing would comprise 21% of all incidents, slightly lower than what we report. In Tampa, removing Drug and Narcotic Violations from the Wellbeing category would result in 31 fewer incidents in the Wellbeing category. In Tampa, this would reduce the Wellbeing category from 42% to 41% of the total incidents, only a 1% difference.

- 33. IR 344-Bates No. 20190508-000426.

- 34. IR 45-Bates No. 20200119-000053.

- 35. IR 411-Bates No. 20190812-000721.

- 36. IR 267-Bates No. 20190313-00231.

- 37. IR 8-Bates No. 20190608-000532; In the incident reports, the names of those involved have been redacted to protect their privacy. This report uses pseudonyms to refer to the veterans involved in the incident reports. West LA VA Welcome Center: The First Step in the Journey Out of Homelessness, U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. (Jan. 30, 2023), https://www.va.gov/greater-los-angeles-health-care/stories/west-la-va-welcome-center-the-first-step-in-the-journey-out-of-homelessness/." AND "VA - West Los Angeles Campus Index, U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs., https://www.va.gov/files/2023-12/West%20Los%20Angeles%20VA%20Medical%20Center%20Map.pdf (last accessed Mar. 4, 2024).

- 38. IR 285-Bates No. 20190313-000232. This police report includes multiple accounts from several different VAPD officers. The officers' accounts are consistent. This analysis of this incident combines the officers' perspectives to seamlessly describe the encounter.

- 39. Rikki A. Roscoe, The Battle Against Mental Health Stigma: Examining How Veterans with PTSD Communicatively Manage Stigma, 36 Health Commc'n 1378, 1378 (2021).

- 40. Sonya Gabrielian, Ashton M. Gores, Lillian Gelberg & Jack Tsai, Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders Among Homeless Veterans in Homelessness Among US Veterans 35, 36 (Jack Tsai ed., 2018).

- 41. Supporting the Behavioral Health Needs of Our Nation’s Veterans, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Nov. 8, 2022), https://www.samhsa.gov/blog/supporting-behavioral-health-needs-our-nations-veterans#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20approximately%205.2%20million,treatment%20within%20the%20past%20year.

- 42. Behavioral Health Issues Among Afghanistan and Iraq U.S. War Veterans, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2012), https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma12-4670.pdf.

- 43. Suicide Among Veterans and Why It Matters, Mental Health First Aid (Nov. 6, 2018), https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/2018/11/suicide-among-veterans-and-why-it-matters/.

- 44. Sonya Gabrielian, Ashton M. Gores, Lillian Gelberg & Jack Tsai, Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders Among Homeless Veterans in Homelessness Among US Veterans 35, 36 (Jack Tsai ed., 2018).

- 45. IR 163-Bates No. 20191010-000213

- 46. IR 28-Bates No.691200335

- 47. United States Department of Veterans Affairs, National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report 4 (2022).

- 48. Suicide Risk and Risk of Death Among Recent Veterans, U.S. Dep’t of Veterans Affs. (July 24, 2019), https://www.publichealth.va.gov/epidemiology/studies/suicide-risk-death-risk-recent-veterans.asp

- 49. United States Department of Veterans Affairs, supra note 47, at 7.

- 50. IR 386-Bates No. 20190728-000686

- 51. The authors presume this category includes patients who are returning (taking back) their prescriptions.

- 52. IR 480-Bates No. 20191130-001061.

- 53. IR 1414-Bates No. UOR 2016-02-1645-5322.

- 54. The specific incident type is “FEDERAL : CFR : 38 CFR 1.218(B) : (13) UNAUTHORIZED LOITERING-SLEEPING OR ASSEMBLY ON PROPERTY.”

- 55. IR 26-Bates No. 691 20200206-000137-739582.

- 56. IR 38-Bates No. 691200890-866664.

- 57. State of Homelessness: 2023 Edition, National Alliance to End Homelessness, https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness/(last accessed Nov. 14, 2023).

- 58. See, e.g., HUD-VASH Vouchers: A Rental Assistance Program for Homeless Veterans, U.S. Dep't of Hous. & Urb. Dev., https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/vash (last accessed Nov. 14, 2023); Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Takes Action to Address Veteran Homelessness, The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/06/29/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-takes-action-to-address-veteran-homelessness/ (last accessed Dec. 13, 2023).

- 59. IR 423-Bates No. IR: 20190818-000748. This Use of Force Review includes reports from several VAPD officers. The officers' accounts are consistent. This analysis of this incident combines the officers' perspectives to describe the encounter.

- 60. Disorderly Conduct Plus as a subcategory includes all incident types with an indication DISORDERLY CONDUCT found in the incidents type text in addition to incident types commonly considered as disorderly conduct, such as unauthorized demonstrations, commercial solicitation, and vending, as well as failure to comply with signage, and improper dumping of rubbish.

- 61. The specific incident types include LOUD- BOISTEROUS AND UNUSUAL NOISE, actions that OBSTRUCTS NORMAL USE OF ENTRANCES- EXITS- FOYERS- OFFICES- CORRIDORS- ELEVATORS- AND STAIRWAYS, and IMPROPER DISPOSAL OF RUBBISH ON PROPERTY.

- 62. This specific incident type is FEDERAL : CFR : 38 CFR 1.218(B) : (06) FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH SIGNS OF A DIRECTIVE AND RESTRICTIVE NATURE POSTED FOR SAFETY PURPOSES.

- 63. IR 1496-Bates No. 673200930.

- 64. IR 1420-Bates No. 673-210377. This veteran patient began fighting with officers in his attempt to free himself from the involuntary hold. Ultimately, one captain used a “hammer fist to the temple area” to take him down and put him hand and leg restraints. He was then transferred to a bed and placed in 4-point hard restraints. His injuries included a bruise to his forehead and a “fat lip.”

- 65. IR 1438-Bates No. 673200546.

- 66. IR 1504-Bates No. UOR 2016-10-22-0827-1280. -0827-1280.

- 67. IR 313-Bates No. 20190417-000359.

- 68. Specifically, these incident types include INCIDENTS: NON UCR INCIDENT: INFORMATION REPORT ONLY and NON-CRIMINAL : INFORMATION REPORT ONLY.

- 69. For example, on the West Los Angeles campus, VAPD officers have access to the California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System (CLETS) which allows them to view federal, state, and local criminal records.; California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System, State of California (2019), https://www.chaffey.edu/police/docs/california_law_enforcement_telecommunications_system.pdf.

- 70. For the purpose of this report, an "outstanding warrant" is an existing, active arrest warrant in a person's criminal record that is for an infraction that is unrelated to the current interaction with VAPD.

- 71. IR 26-Bates No. 20200206-000137.

- 72. IR 49-Bates No. 6176702.

- 73. The remaining categories we created are as follows: Vehicle Accidents, Driving Under the Influence, Bodily Harm, Weapons, Concealment and Falsification, Theft, Arson, Refusing to Be Policed, Threats, Animal Incidents, Lost Keys and Card Access, Emergency Responses, Alarms and Drills, Sex-Related incidents, Deaths. The subcategory Refusing to Be Policed includes incident types in which patients directly resist VAPD policing. This category includes police USE OF FORCE indicated in the incident types as well as the incident type RESISTING OR OBSTRUCTING AN OFFICER.

- 74. The subcategory "Non-Consensual Sex Incidents" likely includes incidents that overlap with the Bodily Harm category, but we have categorized Non-Consensual Sex incidents within the larger category Sex-Related Incidents.

- 75. 76% of incidents categorized as Bodily Harm include the words SIMPLE ASSAULT in the incident type language for Los Angeles, 51% for Tampa, 39% for Queens and 29% for Columbus.

- 76. See: November 2021 report, Figures 1.1 – 1.4.

- 77. In Columbus, Theft became the the second-largest category in the later period, and in Queens, Spatial Control moved down to fifth behind Alarms/Drills and Lost Keys and Card Access.

- 78. See Technical Appendix. As detailed there, following an encounter, a VAPD officer will create an Incident Report where they indicate one or more "incident types" that describe the nature of the encounter.

- 79. 38 C.F.R. § 0.600

- 80. I CARE Core Values, Characteristics, and Customer Experience Principles, U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. (last updated Nov. 16, 2021), https://www.va.gov/icare/core-values.asp.

- 81. I CARE, U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. (last updated Sept. 6, 2023), https://www.va.gov/icare/.