“STUCK”: Los Angeles County’s Abuse and Neglect of People on Mental Health Conservatorships in Jail and Locked Psychiatric Facilities.

“STUCK”: Los Angeles County’s Abuse and Neglect of People on Mental Health Conservatorships in Jail and Locked Psychiatric Facilities.

Los Angeles County is illegally holding hundreds of people on mental health conservatorships in jail and costly psychiatric facilities because it has failed to create sufficient community placements, instead concentrating on building more locked facilities, at great expense.

"STUCK"Los Angeles County’s Abuse and Neglect of People on Mental Health Conservatorships in Jail and Locked Psychiatric Facilities

Executive Summary

Los Angeles County is illegally holding hundreds of people with mental health disabilities in jail and locked psychiatric units long after they should be released.

Los Angeles County holds people in jail even when they don’t have any criminal charges pending. L.A. County holds people in psychiatric hospitals and other locked mental health facilities for months after its own doctors say they are clinically ready for discharge. Last year in L.A. County, more than 800 people were in locked mental health placements who did not need to be there. They were on waiting lists to move to a less restrictive placement, taking up beds needed for other people. This issue is especially harmful to people who have been placed on a mental health conservatorship by the County, which takes away their ability to make decisions about their own lives.

These practices violate the United States and California constitutions, and state and federal disability rights laws. They also meet accepted definitions of abuse and neglect.

In addition, these cruel and illegal practices violate common sense and waste taxpayer dollars. One day in the County Jail’s High Observation Unit costs $650. A day in a County psychiatric hospital costs $1500.

DRC Findings

- L.A. County has held people on LPS conservatorships in the county jail without criminal charges for months due to the lack of appropriate placements.

- L.A. County needlessly holds people in locked psychiatric units for months or even years after their doctors agree they are ready for discharge.

- The County's practices violate federal and state law. They are abusive and neglectful of hundreds of people in locked placements whom the County is supposed to protect.

- These illegal practices waste millions of dollars in public funds that could be used to support people in the community and support their recovery.

The County’s response to the waiting lists has been to build more locked facilities, especially locked subacute mental health facilities intended to transition people out of hospitals and the jail. This approach is misguided. Subacute facilities are still expensive at $450 per day, or $13,950 per month, with no Medi-Cal reimbursement. Of the people on mental health conservatorships on waiting lists last year, 430 were ready to leave their subacute facility and move to the community. Yet they continued to take up subacute beds, at a cost to the County of $6 million per month.

Instead, the County should provide intensive mental health services and housing in the community to everyone on the waiting list. This would cost less than $5000 per month per person. For all 430 people on the waiting list, the cost would be $2.15 million. This would save the County $3.75 million per month compared to what it is paying to keep these individuals in subacute placements they do not need.

More importantly, the County’s practices hurt the people it is supposed to protect. Keeping people on conservatorships in locked psychiatric units when they do not need to be there is not therapeutic and does not support their recovery. People are often placed in restraints and forced to comply with orders that aggravate their disabilities.

In addition, there is evidence of anti-Black racism. Black/African American people are 9% of the LA County population, but 35-40% of the people who have been over-detained at the jail while awaiting transfer to a mental health facility.

The following report from Disability Rights California ("DRC”) describes our investigation of this problem. We provide details about our findings, including stories from people who are stuck in the system. We also provide recommendations from two of the nation’s leading mental health experts – Elizabeth Jones and Dr. Sam Tsemberis – about how the County can improve its mental health system, correct the existing illegalities, and save money.

DRC’s experts first recommend that L.A. County increase the availability and intensity of wraparound mental health services provided by Full Service Partnership teams. These teams should meet the program fidelity requirements for Assertive Community Treatment (“ACT”) teams. L.A. County’s current Full Service Partnership teams do not meet these standards and are not strong enough to support most people on conservatorships leaving locked facilities. San Diego is a good example of a county that has strengthened its wraparound services in this way.

DRC’s experts also recommend that the County provide its strengthened wraparound teams with rental subsidies and other property management costs so people leaving locked facilities have housing options that are integrated into the community.

Finally, the experts recommend that L.A. County reform the process for discharge planning from locked institutions and educate stakeholders about less restrictive and more effective community options that enhance recovery and quality of life.

DRC’s experts agree that L.A. County can end illegal waitlists and free people from locked institutions by increasing the availability of intensive community-based mental health services and housing. This will open up beds for people currently in hospitals, other locked placements and the jail, awaiting a less restrictive placement. If implemented, the experts’ recommendations will ensure that people ready for discharge can move back into community placements in weeks instead of months or years.

L.A. County’s abuse and neglect of people currently on mental health conservatorships is very serious but could easily become worse. Recently, the State Legislature passed the CARE Act and another law that makes it easier to use forced treatment and place people on a mental health conservatorship. L.A. County could soon become responsible for many more people than the 4,600 people currently on conservatorships. This crisis must be resolved now.

Report on Los Angeles County's Abuse and Neglect of People on Mental Health Conservatorships in Jail and Locked Psychiatric Facilities

Mental Health Conservatorships in Los Angeles

Los Angeles County (“L.A. County” or the “County”) places an estimated 4600 people on mental health conservatorships under the Lanterman-Petris-Short (“LPS”) Act each year.1 Pursuant to the LPS Act, when a court finds that an individual is “gravely disabled” due to a mental health disability—meaning that they are unable to provide food, clothing, and shelter for themselves—the court appoints a “conservator” to make legal decisions on their behalf.2

A person on an LPS conservatorship loses control of many basic rights, including the power to make key decisions about their own mental health treatment, finances, and housing. When conservators decide where a person on an LPS conservatorship should live, they are legally obligated to place the person in “the least restrictive alternative placement.” (Welf. & Inst. Code § 5358, subd. (a)(1)(A).) This means that, whenever possible, conservators should place people in apartments in the community with a supportive team providing “wrap-around” mental health services rather than locked psychiatric institutions or large, congregate living facilities.

The Los Angeles Office of Public Guardian (part of the County Department of Mental Health) serves as the conservator for individuals who do not have family or friends able or willing to provide support. It is responsible for the care and placement of approximately half the people on LPS conservatorships in the County – an estimated 2300 people per year.3 L.A. County has a special duty to protect these individuals, having assumed total control over their lives. The remainder of people on LPS conservatorships have private LPS conservators, who are often family members.

Disability Rights California’s Investigation

Disability Rights California (“DRC”) is the protection and advocacy system for the State of California. DRC is charged under federal and state laws with protecting the rights of and advocating on behalf of people with disabilities.4 DRC opened its investigation after receiving complaints that Los Angeles County Jail was illegally detaining people on LPS conservatorships. DRC discovered not only that these reports were accurate, but that the unnecessary confinement of people on conservatorships extends beyond the jail to every level of the county’s system of care.

Two nationally recognized experts on mental illness and mental health service systems assisted DRC in this investigation: Elizabeth Jones5 and Dr. Sam Tsemberis.6 (See Appendix A for a description of their qualifications and other details of our investigation.) As part of this investigation, we conducted on-site inspections of mental health facilities, interviewed staff and patients, and reviewed documents, data, and reports relating to L.A. County’s system of care for people with mental health disabilities, including those on conservatorships.

This investigation does not address the needs of people who are a danger to themselves or others, or who are under “Murphy” conservatorships because they continue to pose a danger to others.7 Rather, this report addresses the hundreds of people whom treating professionals, DRC consultants, and facility staff agree are not dangerous and are ready for release. Although they may remain symptomatic, there is no basis to hold these individuals in a locked facility because their clinical issues, with proper support services, can be effectively addressed in the community. And freeing up beds in locked placements will offer more short-term and long-term placement options for people who may be gravely disabled or pose a danger and genuinely need this level of care.

Finding #1:

L.A. County has held people on LPS conservatorships in the county jail without criminal charges for months due to the lack of appropriate placements.

Our investigation found that, for several years, the Public Guardian directed the County Sheriff to detain hundreds of people on LPS conservatorships illegally in County jail even after their criminal charges were dismissed, usually because they were initially found “incompetent to stand trial” and their competency could not be restored after treatment.8

County officials admitted in March 2023 that the Sheriff “over-detains” many people on conservatorships who “remain in jail after they otherwise would have been released” because the Public Guardian cannot “secure an appropriate placement.”9 Through our investigation, we found that many people were only released after the County Public Defender filed writs of habeas corpus challenging their unlawful imprisonment.10 Last year, the state courts began sanctioning the Public Guardian in some cases for failing to find placements for people in jail on conservatorships.11

As state and federal law make clear, holding people on conservatorships in jail without charges is flatly illegal. Courts have found that for people under conservatorships, “[i]f it occurs at all, confinement is never in a jail, prison, or an institutional environment designed for the punishment of persons convicted of crimes.12” Courts also do not accept difficulty in finding a placement for people on LPS conservatorships as a justification for holding them in jail against their will.13 In the past, federal courts have found L.A. County liable for tens of millions of dollars in damages for detaining individuals in jail after they were cleared for release, with liability attaching for an over-detention of even one day.14

Held in Jail Illegally for 8 Months Without Charges.

Kendra is an 47-year-old, African American woman on a mental health conservatorship. The Public Guardian placed her in a board and care facility with 120 other residents. Despite being on a conservatorship, DMH did not provide Kendra with intensive wraparound mental health services to support her recovery. She felt alone and had persistent conflicts with staff, whom she perceived as racist.

One day, Kendra got upset, took drugs, and verbally threatened another resident. Instead of calling a crisis team, the board and care called the police, who arrested Kendra and took her to County Jail. Kendra was charged with terrorist threats and served 60 days. But when her time was up, she remained in jail for eight more months because the Public Guardian could not find a locked placement for her. Kendra described to DRC how she was locked in her jail cell alone most of the time and denied showers when she did not behave.

L.A. County’s over-detention of people on LPS conservatorships in the jail is destructive and traumatizing. For more than 25 years, L.A. County has been subject to federal review and court orders for violating the rights of people with mental disabilities in the jails; a court-appointed monitor continues to find that the jail is out of compliance. The L.A. County Jail is a toxic environment for anyone, but especially those with mental health disabilities who are often subject to conditions that amount to solitary confinement. Even in the jail’s mental health units, the jail isolates people with serious mental disabilities for 23 hours a day in cells marked by abject filth and squalor. A July 2023 report from the Sybil Brand Commission to the L.A. County Board of Supervisors called the conditions “abominable” and observed feces, food waste, trash, and cockroaches in these cells.15

Numerous studies have shown that subjecting individuals with severe mental health disabilities to solitary confinement—including prolonged isolation without opportunities to receive supportive counseling, socialize with others, limited out-of-cell time, and the deprivation of sensory inputs—increases the risk of decompensation and self-harm. When we interviewed Kendra, she said: “I did get PTSD in the jail.".

These harms disproportionately impact Black/African American people, who are vastly overrepresented in the County jail. While Black/African American people make up less than 10% of the County’s overall population, they make up approximately 30% of people in the jail. They make up over 38% of people with serious mental disabilities in the jail’s special housing units, including those who meet criteria for LPS conservatorships.16 Based on our investigation, DRC estimates that the number of Black/African American people who have been over-detained at the jail while awaiting transfer to a mental health facility is consistent with these figures, at approximately 35-40%.

Figure 1 - Exterior of LA Jail Twin Towers

Figure 1 - Exterior of LA Jail Twin TowersBased on data DRC obtained as part this investigation, DRC found not only that L.A. County over-detains a disproportionate number of Black/African American people, but also that it illegally holds Black/African American people for longer periods of time as compared to other racial and ethnic groups. As but one example from DRC’s data sample, the three people on conservatorships who were held the longest in the County Jail without charges were all Black/African American individuals. Overall, the illegal over-detention of Black/African American individuals ranged from 250 to 400 days.

In December 2023, the Sheriff adopted a new policy finally ending the practice of holding people on conservatorships in the jail.17 However, as of February 9, 2024, there were still 126 people in the jail awaiting transfer to a mental health facility.18 According to records kept by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, these individuals’ criminal cases have been dismissed. The County has no legal basis for holding them in jail. The L.A. County Department of Mental Health recently admitted that courts are imposing daily sanctions on the Public Guardian because it continues to leave people on conservatorships in jail.19

Even with the Sheriff’s new policy there is still no sustainable solution. As discussed below, wait lists for community placements and less restrictive mental health facilities remain many months long causing people to languish in institutional settings.

DRC’s investigation found that the Public Guardian’s new practice is to move people on conservatorship from the jail to urgent care centers, until a longer-term locked placement can be located.20 These urgent care centers are not licensed for stays beyond 23 hours and 59 minutes.21 People sit on chairs because there are no beds for sleeping. Without regular meals or set activities, some people on conservatorships have simply left the urgent care centers on their own, although they have no supports or housing.

Dr. Elizabeth Jones, who consulted on this report and has decades of experience working with people with mental disabilities, has expressed concern about how the current set-up re-traumatizes already distressed people who are stuck in the system and puts them at risk of future unnecessary institutionalization. In her words, “There’s no hope of recovery when you keep cycling in and out of locked wards.”.

Finding #2:

L.A. County needlessly holds people on locked psychiatric units for months or even years after their doctors agree they are ready for discharge.

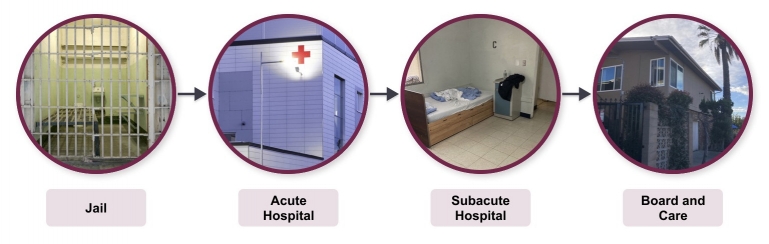

DRC’s investigation found through interviews and site visits that the County jail is not the only illegal placement in which people are “stuck.” Many people on LPS conservatorships are stuck in acute psychiatric hospitals and locked subacute mental health facilities for months or years after clinical professionals have deemed such placements unnecessary.

In the words of Laura, a person who was on a conservatorship previously, “there’s a frustrating system you have to go through” with conservatorship placements. People are moved in lockstep from one locked facility to another without regard to whether they could successfully live in the community. Many other conservatees echoed Laura’s sentiments as they endured a rotation of psychiatric facilities for years while they slowly made their way through DMH’s placement system. As we discuss in more detail below, the resulting delays and waiting lists violate the Americans with Disabities Act.

Laura's Journey

DRC’s finding is consistent with a recent DMH report entitled “Establishing a Roadmap to Address the Mental Health Bed Shortage,”22 in which DMH identified “significant bottlenecks at the subacute level of care” and found that “readmissions are currently using up capacity at a rate that is higher than many regions in California.”23 Previous DMH reports also found that one significant contributing factor is that “[p]ublic guardians assigned to persons on conservatorship status can influence discharge planning by rejecting placements and demanding that the patient be transitioned from [an] inpatient unit to a locked facility.”24

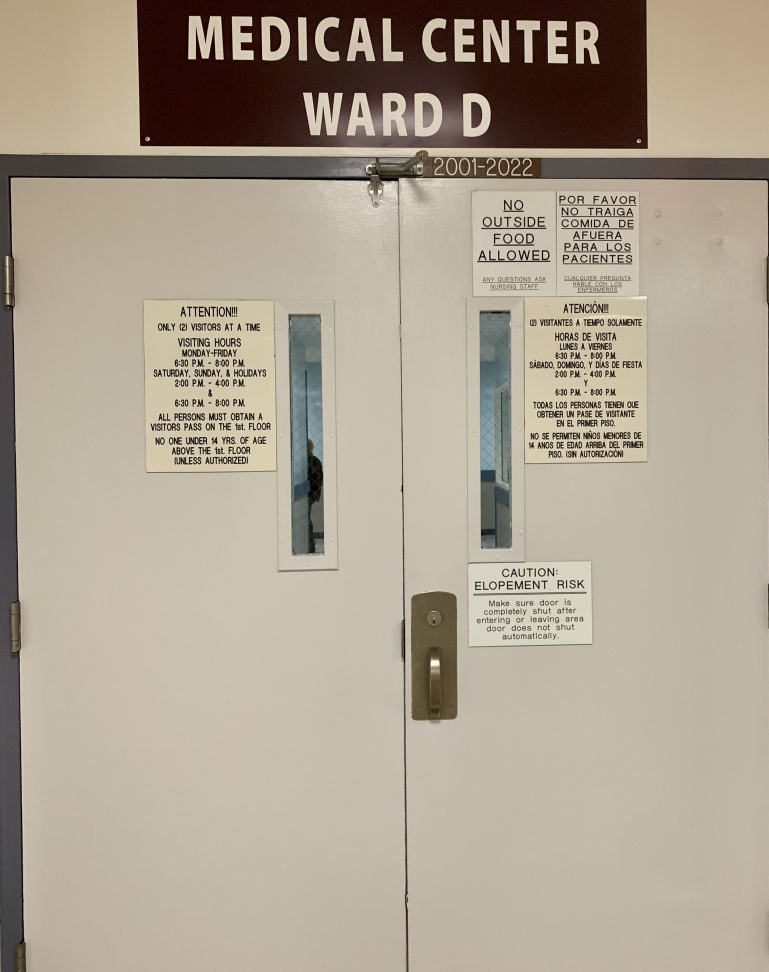

Figure 2 - Entrance to a psychiatric ward with a sign saying “CAUTION ELOPEMENT RISK".

Figure 2 - Entrance to a psychiatric ward with a sign saying “CAUTION ELOPEMENT RISK".Specifically, our investigation revealed that, after jail, an urgent care unit, and/or a psychiatric emergency room, DMH frequently transfers people in the conservatorship process to inpatient acute hospitals operated by the County Department of Health Services (“DHS”).25

While stays in these expensive acute hospitals should be brief—no longer than a week or two at most—we found that DMH holds many people on conservatorships in locked psychiatric units for months or years after they are ready for release. The average length of stay in County hospitals is two-and-a-half months, as compared to an average stay of a single week in DMH’s outside contract hospitals.

L.A. County General Hospital’s acute inpatient psychiatric unit, the Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center, has an even longer length of stay, averaging four-and-half months.26 Some patients stay even longer, typically because no less restrictive placement will accept them. When DRC asked Hawkins staff how many of their patients on conservatorship were ready for discharge, they responded: “all.” Hawkins is a safety net hospital – it will take people who have been rejected by contract hospitals because of a history of violence, medical or forensic issues, etc. Of the 50 patients there at the end of 2023, half were on conservatorships or in the process of being placed on a conservatorship, itself a lengthy process. DRC interviewed two people who the Public Guardian had placed at Hawkins for 423 days and 593 days respectively.27

| Table 1 - Placements and Waiting Lists for People conserved by Office of Public Guardian – 2021-202228 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Length of Stay | Number in Placement | Number Waiting for this Placement | Average Time to Wait for this Placement | |

| County Acute Inpatient Psychiatric | 75 Days | 128 | Unknown | Unknown |

| State Hospital | Several Years | 326 | 29 | 400+ Days |

| Locked Subacute IMD Beds | 2 Years | 1175 | 407 | 146 Days |

| Enhanced Res. Services | 15 Months | 329 | 436 | 87 Days |

| Full Service Partnerships | Unknown | 225 | Unknown | Est. 6 Months |

Medical staff recognize that this length of stay is a problem. One County doctor told DRC, “Nobody wants to be in the hospital; we are not supposed to be housing patients long-term.” A county hospital patient who had been ready for discharge for 18 months said to DRC, “I feel like a prisoner of war.” All those we interviewed said they just wanted to be released.

L.A. County has acknowledged the problem but has done little to combat it. In 2019, L.A. County officials estimated that “three-quarters of all patients in DHS acute psychiatric facilities [were] waiting for various lower level of care placements in the mental health continuum of care... Waitlists to transition to the next level of care are long and getting longer, especially for hospital clients on a mental health (“LPS”) conservatorship.”29

Figure 3 - Image of a seclusion room in a subacute facility in which people are forcibly restrained.

Figure 3 - Image of a seclusion room in a subacute facility in which people are forcibly restrained.Holding patients for longer than medically necessary is illegal, counter-therapeutic and can be outright harmful. According to one staff nurse, forcing patients to endure such delays “actually increases their level of agitation.”30

When patients get frustrated and act out, they are at heightened risk of being forcibly restrained—which can involve strapping patients’ arms and legs to a bed or tying their wrists and ankles. This is a dangerous and traumatizing process and can cause a deterioration in people’s mental state.

Black people are disproportionately impacted by these harmful practices and are overrepresented in the institutions that feed into the County’s conservatorship system. Empirical research has also confirmed the existence of embedded, structural discrimination against Black/African American people who receive institutional care, both with respect to admission decisions and the quality of care once institutionalized.31

DRC’s investigation revealed that—after releasing individuals on LPS conservatorships from jail, an urgent care center, or an acute psychiatric hospital—DMH’s default is to place them in subacute facilities. These are locked facilities, sometimes licensed as skilled nursing facilities and intended for stays of 12 to 18 months.32 DMH contracts with 19 subacute facilities with a total of 1175 beds, almost all occupied by people under conservatorship.33 While less expensive than the Jail or an acute hospital, subacute facilities are still costly at $450 per day, and do not qualify for Medi-Cal reimbursement.

Figure 4 - Image of the subacute facility in which Kendra was held.

Figure 4 - Image of the subacute facility in which Kendra was held.Admission to a subacute facility is a slow process, requiring approval by the conservator, the court, the facility and the DMH Intensive Care Division, which is the gatekeeper for these placements. Table1 shows that in 2023, 407 people on conservatorships were on the waiting list for a subacute bed, waiting an average of almost five months.34

With so much demand, subacute facilities can be selective, often rejecting applicants for trivial reasons. County Health Services staff at the acute hospitals report great difficulty in navigating the process, which also contributes to lengthy delays.

While L.A. County describes “subacute” facilities as providing a “lower level of care” than County hospitals, these facilities are still extremely restrictive. Living areas are barren and institutional, surrounded by fences and barbed wire with little green space. The focus is on compliance and following regimented daily regimes.

When DRC interviewed individuals on conservatorships in these locked subacute facilities, several people expressed their deep desires to engage in common life activities like going to a park or cooking for themselves but no way to do so. One conserved individual, “Greg,” described being locked in psychiatric facilities for years and not having the opportunity to go outside for a walk, sharing that he had “no freedom” and that his “muscles changed to jelly.”.

Once in a locked subacute facility, people are again stuck long after they are ready for release. Although intended as transitional placements, the average length of stay in L.A. County is two years and more.35 Facility administrators confirmed that residents routinely wait six months or more to leave these facilities after their doctors agree they are ready for discharge, which explains the longer length of stay. DRC’s experts confirmed that restrictive conditions such as these are counter-therapeutic for individuals who have stabilized and are ready to live in the community.

Held in a Subacute Facility for Months.

After eight months of languishing in jail, DMH transferred Kendra to a locked subacute facility in El Monte, where she has been for six months. She is on a waiting list for transfer to a lower level subacute, and after months there, she will be on a waiting list for a community placement – a process that could take years.

Kendra hates the locked subacute facility, describing it as cramped and boring. “They don’t even have Bingo!”, she complained. She wants to go back to a board and care, and DRC’s experts agree that she could do so now if she had the support on a robust Full Service Partnership team to help her manage crises and problems as they arise.

The County does not track the number of people in subacute facilities who are ready for discharge, but last year 436 people on conservatorships with the Public Guardian were on the wait list for DMH’s Enhanced Residential Services (“ERS”) program, which is a typical step-down placement for someone in a locked subacute facility.36 See Table 1 above. The wait list was over three months long. This means that more than 400 people took up beds in subacute facilities for three months or more when they did not need to be there, contributing to the bottlenecks and backlogs in the system.

The ERS program provides intensive, on-site mental health services for clients in seven board and care facilities. DRC inspected a board and care facility where ERS staff were available on a daily basis, offering activities, help connecting with jobs and education, and support with residents’ recovery. Of the 2200 people on Public Guardian conservatorships last year, 329 were in the ERS program, although judging from our interviews and the waiting list, many more would have benefited.

Figure 5 - Exterior of a Board and Care facility

Figure 5 - Exterior of a Board and Care facilityDMH also discharges some people on conservatorships to board and care facilities37 without additional support, but this leaves them at risk of cycling back into the jail or hospital. Board and cares are institutional, congregate and lack privacy, and are more expensive than other community residential settings. With as many as 150 residents with serious mental health disabilities, these facilities are chaotic and not homelike. Former residents complained to us about having little control over their lives and being exposed to others’ drug use.

Instead, DRC’s experts recommend that every person leaving a locked facility should have the option of an apartment or other home in the community and the support of intensive, wraparound mental health services through a “Full Service Partnership” (“FSP”) team. However, the FSP must offer services that meet the nationally recognized fidelity standards for Assertive Community Treatment. Later in the recommendations section of this report, DRC’s experts explain these standards and the need to include supportive housing. DMH’s FSPs fail to offer services of sufficient intensity to meet these standards, do not include supportive housing, and have waiting lists of six months or more. Given these limitations, only 225 people on conservatorships in L.A. were enrolled in FSPs last year, down from 260 the previous year.38

Finding #3:

The County’s practices violate federal and state law. They constitute abuse and neglect of hundreds of people in locked placements whom the County is supposed to protect.

Holding people in locked placements when they are ready for release and do not need to be there constitutes “abuse” and “neglect,” as defined in state and federal law.39 It violates a conservator’s duty under state law to place people in “the least restrictive alternative placement.” It also violates the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment because the County is disregarding the judgment of their treating professionals. Youngberg v. Romeo, 457 U.S. 307, 317, 324(1982) (“When a person is institutionalized—and wholly dependent on the State, … courts must show deference to the judgment exercised by a qualified professional” in determining whether treatment is constitutionally adequate).

Holding people in locked institutions also violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”), which requires services to be provided “in the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs of qualified individuals with disabilities.” 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(d). In Olmstead v. L.C. ex rel. Zimring, 527 U.S. 581, 607 (1999), two people with mental health disabilities were held in a state hospital in Georgia long after their treating doctors said they were ready for release to the community. As here, the government agency claimed community placements were unavailable. The Supreme Court found that this restrictive placement violated the ADA.

Olmstead, 527 U.S. at 607. As in the Olmstead case, people with mental health disabilities in L.A. County face unreasonable delays in moving from a locked placement to the community. Since L.A. County can create additional community placements at less cost, its long wait lists are unnecessary and a waste of public funds, so it has no defense against this ADA violation. These delays affect the mental health of clients and are a violation of their legal rights under the ADA and the Olmstead decision.

The people we interviewed – all individuals who had experienced a conservatorship – put it directly:

“There’s no reason for me to be locked up here.”

“I wish I had a place to live just to see how life could be.”

“I wish I had my own place, independent.”

“I’d like to find a little apartment. I have schooling in mind.”

“I want to study and go to a good school.”

The County’s practices also disproportionately impact Black/African American people with mental health disabilities, in violation of anti-discrimination laws. See, e.g., Cal. Gov. Code § 11135; 22 C.C.R. § 11154 (prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, including by utilizing “criteria or methods of administration” that have the “purpose or effect of subjecting a person to discrimination”). As discussed in Findings 1 and 2, the County’s practice of housing people on LPS conservatorships in jail discriminates against Black/African American people, who are significantly more likely to be illegally housed in jail while they await mental health treatment. In addition, the County’s practices cause Black/African American people to endure disproportionately longer periods of unnecessary incarceration and institutionalization as compared to other groups. The consequences of these practices are alarming: Black/African American people are disproportionately deprived of their rights and subjected to long periods in counter-therapeutic locked settings, harming their mental health and increasing the likelihood of decompensation and cycling.

Finding #4:

L.A. County’s illegal practices waste millions of dollars in public funds that could be used to support people in the community and support their recovery.

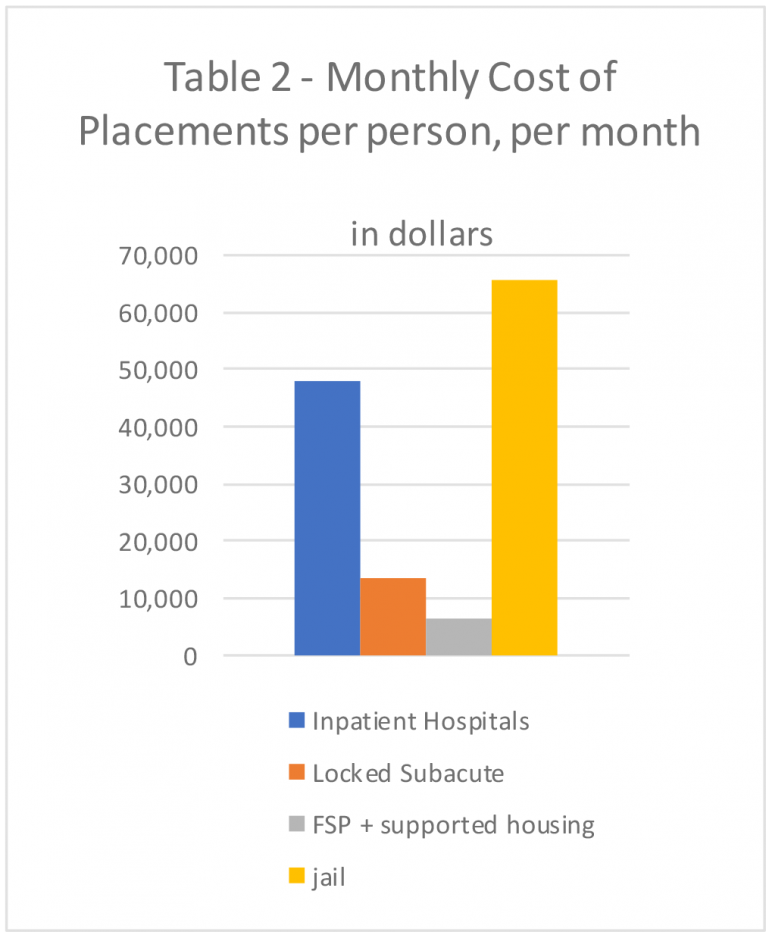

The financial cost of warehousing people in locked institutions is staggering. A single day in the County Jail’s mental health unit for people with serious mental disabilities costs $650 per person,40 for a total of $19,760 per person, per month. But in addition, courts are now imposing sanctions of up to $1500 per day for over-detention of people on conservatorships.41 This brings the total to $65,360 per person, per month.

Similarly, one month at a County inpatient psychiatric unit costs $46,600,42 almost none of which is reimbursed by Medi-Cal because these long stays do not meet medical necessity criteria.43 On average, mental health patients remain at County acute psychiatric hospitals nine weeks longer44 than those in DMH contract hospitals. Thus, the County is wasting more than $54 million per year45 paying for the extra two months that County patients remain, on average, in locked inpatient units. If they were promptly discharged to a lower level of care, the cost would be a fraction of this total.

Table 2: - Monthly Cost of Placements Per Person, Per Month in Dollars

Table 2: - Monthly Cost of Placements Per Person, Per Month in DollarsL.A. County also contracts with outside psychiatric hospitals such as Gateways and Aurora Las Encinas for long-term placements at approximately $30,000 per month. Administrators report that patients often stabilize in four-to-six months but may wait another six months before a less restrictive facility is available. Since L.A. County pays regardless, this amounts to an additional $180,000 in needless costs per patient stay.

When a patient at a County hospital is eventually accepted in a locked subacute facility, L.A. County pays $13,950 per person, per month, with no Medi-Cal matching funds.46

Notably, community placements are far less expensive. Enrollment with a DMH Full-Service Partnership (“FSP”) team is $1270 per month, which is partially reimbursable by Medi-Cal.47 FSP teams provide support and crisis services in the community (although DRC’s experts recommend increasing the intensity of the program to improve outcomes). With the addition of interim or permanent supportive housing costs, a community placement with a strengthened FSP team is less than $5000 per person per month.48

The County reports that 430 people on mental health conservatorships were waiting to leave their subacute facility and move to the community. Yet they continued to occupy subacute beds, at a cost to the County of $6 million per month. Instead, the County should provide intensive mental health services and housing in the community to everyone on the waiting list, at a cost of $2.15 million per month. This would save the County $3.75 million per month compared to what it is paying for subacute placements that people do not need.

Figure 6 - Image of clients in a community support program.

Figure 6 - Image of clients in a community support program.Although the County has made incremental increases to community placements, most resources are focused on adding more locked subacute facilities. In 2022, the L.A. Board of Supervisors approved subacute facility contracts totaling $205 million annually. In June 2023, the Board of Supervisors approved an increase of $8 million for 2023-24 alone.49 In December 2023, the Board also approved a $169 million budget for construction of a new subacute facility.50

L.A. County plans to build a “Restorative Care Village” that will add 128 new locked beds at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars, but financing and construction will be lengthy process.

More locked beds in five or ten years will not solve the crisis described here. Instead, it will simply create even more institutions in which people will be “stuck.” Even assuming this number of locked placements is necessary, holding people for up to six months after they are ready for release, as is the current practice, represents another needless cost as well as a violation of the ADA and Constitution.

Given the illegality of holding people needlessly in locked placements and the funds wasted to do so, DMH could create intensive placements in the community, individualized to the person’s needs, for all the people on conservatorship on waiting lists. This would open up beds in locked facilities to accept the people who do meet medical necessity criteria. The expert recommendations below describe steps the County should take.

Recommendations

L.A. County DMH recognizes that there are “significant bottlenecks” in its system, though it sees the solution as “expanding the capacity of DMH’s subacute level of care.”51 DRC’s experts disagree.

DRC’s experts formed the recommendations set forth below based on information obtained from site visits, interviews with providers in the County mental health system, and conversations with individuals subject to LPS conservatorships, their family members, and community members. These recommendations are informed by evidence-based studies as well as DRC’s experts’ years of clinical and administrative experience with programs that have proven effective with similar mental health systems across the country.

DRC’s experts recommend that, rather than increasing the number of locked facilities, building more institutions, or funding more congregate settings, DMH must make a significant commitment to implementing a comprehensive array of integrated community-based services and supports. Specifically, DRC’s experts recommend: (1) increasing the capacity and intensity of mental health services provided through Full Service Partnership (“FSP”) teams and ensuring they meet the program fidelity criteria for Assertive Community Treatment; and (2) providing subsidies to rent private housing units or ensure permanent supportive placements for people enrolled in the strengthened FSP teams. The goal is for people in locked placements to access appropriate community placements quickly, instead of waiting for months and years after they are ready for discharge.

DRC’s experts also recommend reforming DMH’s antiquated, lock-step discharge practices that essentially force people to move from one overly restrictive setting to another even when their clinical status does not require it. Specifically, they recommend including an independent clinician in DMH’s discharge decisions and training the Public Guardian’s Office and court participants about the benefits of community placements, the harms of overly restrictive placements, and the value of a recovery model when working to release individuals on LPS conservatorships from illegal and counter-therapeutic settings.

Recommendation #1:

Increase the capacity and intensity of mental health services provided through Full Service Partnership teams, ensure these teams meet the program fidelity criteria for Assertive Community Treatment teams, and dedicate these services to supporting people leaving locked settings.

People ready to leave locked facilities must have a safe place to live in the community and sufficient mental health services to support a path to recovery. DRC experts recommend that L.A. County direct DMH to (1) expand the number of FSP teams until waiting lists for services are no more than few weeks long for people leaving locked settings, and (2) ensure the FSP teams meet national standards for Assertive Community Treatment (“ACT”).

State regulations require FSP teams to offer a wide range of clinical and supportive services, including 24/7 crisis response, mental health treatment, integrated substance use and mental health treatment, peer support, and supported employment services.52 But L.A. County DMH has not set standards for interdisciplinary staffing, service intensity, and caseload size that are consistent with accepted national standards for ACT teams. Meeting program fidelity standards will ensure the proper level of care for people leaving locked institutions.

As originally conceived, FSPs were based on the Assertive Community Treatment model, which requires fidelity to detailed program standards. In the ACT model, teams of professionals and peers use a person-centered recovery approach53 to provide individuals with “whatever it takes.” The ACT model also provides support for employment, education, volunteer work, and peer support specialists who help with restoration of social and community networks following periods of hospitalization or incarceration.

FSP/ACT teams that also include a supported housing component are known as “Housing First” teams. When operated with fidelity to the Housing First model, there is substantial research and evidence showing that this approach reduces hospitalization, incarceration, and homelessness, that it is cost effective (reduces acute care and jail costs), and consistently results in a client’s stability in the community and improved quality of life.54

Dr. Sam Tsemberis, who consulted on this report, is a national expert who pioneered the “Housing First” model and is familiar with both the ACT model and the implementation of FSPs in L.A. County. In his opinion, L.A. County does not fund existing FSPs to provide services of sufficient intensity, as compared to the authentic ACT model. Dr Tsemberis explained: "The staffing ratio in L.A County is too often one caseworker to 20 or even 30 clients. This is far too high to serve people with severe mental illness and doesn’t meet the ACT fidelity standards of 1 to 10. Furthermore, L.A. County FSP teams do not always include sufficient interdisciplinary staff such as psychiatrists, nurses, or peer specialists to provide the full range of needed services and supports.”

With the current system, Dr. Tsemberis explains that “there is too big a gap” between the around-the-clock structure of a locked facility and what a regular FSP can offer. This is especially true if the FSP team cannot initially provide multiple visits each week and has no access to housing. He explains further:

One example is San Diego County, which models its FSP programs to meet ACT program fidelity and uses FSP teams to help move people out of hospitals and locked subacute facilities.55 In San Diego, each ACT/FSP team serves an average of 125 people with a staff ratio of 1:10. The cost is $26,000 per person annually56 or $2200 per month. This is more than the L.A. County rate of $1270 per month. However, the San Diego program complies with the interdisciplinary staffing patterns and caseload ratios required by ACT standards. Adhering to these standards is essential to ensuring the proper care and treatment of people with serious mental disabilities in the community. Los Angeles should adopt the ACT fidelity standards as guiding principles for operating the county’s FSP programs, as well as providing the rent subsidies described below.

If DMH expands and intensifies its FSP program to meet ACT standards, it will be able to reduce the high number of individuals on LPS conservatorships who are being subjected to unnecessary and prolonged stays in locked settings. Once discharged to the community, the FSP/ACT program will prevent them from cycling back to these facilities.

Recommendation #2:

Provide the strengthened FSP/ACT teams with rent subsidies and other property management costs so people leaving locked facilities have housing options that are integrated into the community.

For people on a conservatorship leaving locked placements, DMH and the Public Guardian must provide housing as well as an FSP/ACT team. FSP/ACT teams should also include a supported housing component and function as “Housing First” Teams.57 DMH should not limit placement options to board and care facilities, which are congregate, institutional, and too restrictive for many people on conservatorships.

Permanent Supportive Housing (“PSH”) is also a widely used and effective approach. When available and appropriate, these placements can be effective if combined with the support of an FSP/ACT team. However, the current need for Permanent Supportive Housing already greatly outstrips demand. Multiple County departments and agencies are developing more Permanent Supportive Housing, but the process typically takes years to complete.58

An interim option is for DMH to develop its own version of the federal housing voucher program, as is done in other states and cities. While no substitute for permanent housing, a local voucher program can provide FSP/ACT team clients with access to private rental housing currently available in the community. With vouchers (or other forms of rent subsidies), programs can access market rate apartments or houses, and more housing placement options would be immediately available. This would also meet the legal requirements for placements that are the “least restrictive” and most “integrated into the community.”.

The L.A. County Department of Health Services is already using this “Housing First” model in its “Housing for Health” program in collaboration with the property management services provided by the non-profit Brilliant Corners. Brilliant Corners has developed landlord networks and manages the apartment acquisition, lease negotiations and other property management issues for clients who receive intensive support and treatment services from County service providers.

This program model can be expanded to serve DMH patients leaving locked facilities. Dr. Tsemberis explains:

“We need more apartments and support and treatment services provided by enhanced FSPs that meet the ACT criteria. Currently, the available housing options do not provide adequate clinical service support and treatment. They are either: (a) supportive housing, often a single building with many clients diagnosed with severe mental illness and few on-site services, or (b) apartments in the community where the case management provided is inadequate to meet the clinical needs of the clients and there is usually little or no housing or property management support. Clients living in these housing options need an enhanced FSP/ACT team to provide the treatment and support.”

If the County fully subsidized housing at an estimated $2500 per month for a studio apartment and enrolled each individual in an expanded ACT/FSP team at $2200 per month, the total cost would be $4700 per month. This is less than half that of a subacute bed at $13,950 per month or more. The ACT team services would be of equal intensity, but in a less restrictive setting. Plus, the FSP/ACT team support would qualify for Medi-Cal reimbursement, which is not available for the County’s current subacute facilities.

Recommendation #3:

Reform the process for discharge planning from locked institutions and educate stakeholders about less restrictive and more effective community placement options that enhance recovery and quality of life.

The prolonged stays people placed on LPS conservatorships are experiencing in locked institutions appears to be the result of DMH’s lock-step system that essentially requires people to move through a series of secure psychiatric facilities before they can be considered for direct placement in a community program that provides intensive wraparound services. The insistence by DMH (including the Public Guardian) and courts on placing people in overly-restrictive settings reflects a fundamental misunderstanding and lack of awareness of the decades of scientific research reporting on the effectiveness of community based care when utilizing ACT and Housing First programs for this population.

As DMH designs and implements alternative support services and housing to supplant and reduce the use of restrictive congregate settings, it will be critical for L.A. County to offer information and training to both the Public Guardians and all participants in the judicial process about the benefits of community placements and the harms of placing individuals in locked and counter-therapeutic settings. The training should be mandatory for DMH staff and include detailed information about the effectiveness of ACT and Housing First, the recovery model, peer support, and other evidence-based interventions. The training should also include trauma-informed, culturally responsive treatment, and person-centered care approaches. The training should educate participants about the negative impact of excluding directly impacted people from the decision-making process or ignoring their expressed wishes about housing and programmatic supports. DMH should make every effort to include the judges, their staff, prosecutors, defense counsel, and other judicial participants in these trainings.

DRC’s experts also recommend that DMH retain and/or consult with independent clinicians and peer staff with expertise in the full range of community-based housing and service options into the actual discharge and placement planning process. These independent clinicians and peer staff should be included when DMH makes risk-assessments and level of care determinations. Such staff should be empowered to advise the courts and the Public Guardian about appropriate community-based housing and FSP services. Involving individuals with community-based expertise into DMH’s planning processes will be crucial in helping DMH better support individuals in less restrictive settings, including by tailoring ACT and supported housing services to meet individual needs.

Finally, to further support L.A. County’s efforts to release those who are currently “stuck” in its locked settings, the County can implement a pilot utilization review program for people under conservatorship. As part of this pilot utilization program, an independent clinician should review clinical records and engage in peer-to-peer meetings to assess readiness for discharge in light of community-based services appropriate to the individual. A pilot utilization program of this sort is in line with the recent DMH report submitted to the Board of Supervisors that specifically recommended “strengthening DMH’s internal governance and oversight of the full continuum of mental health resources.”59

Conclusion

This report documents how hundreds of people are stuck involuntarily in locked treatment facilities longer than is necessary, either legally or clinically. Based on DRC’s investigation, it appears that people are stuck in these settings due to: (1) severe shortages of intensive, wraparound mental health services and community-based supportive housing programs; (2) DMH’s outdated, risk-averse, institutional discharge planning practices, which are not evidence-based; and (3) the Public Guardian’s routine insistence that people move from one overly restrictive settings to another, even when their clinical status does not require it.

This is a pressing issue, as the number of people at risk of getting stuck in the system will only increase in the coming months as recent state initiatives bring more people with mental health disabilities under County control. The introduction of CARE Court60 and statutory changes to the definition of grave disability61 will make it easier to place more people on conservatorships. Yet as this report shows, the County now cannot provide for the 4600 people currently on conservatorships.

To address the pervasive problem of individuals on LPS conservatorships getting stuck in the system, DRC’s experts recommend: (1) increasing the capacity and intensity of mental health services provided through Full Service Partnership/ACT teams; (2) subsidizing private housing units for people enrolled in ACT/FSP teams; and (3) reforming the process for discharge planning from locked institutions and educating stakeholders about placement options that enhance recovery. These recommendations align with DMH’s own commitment to a recovery-based system of care,”62 and the principles in California’s Mental Health Services Act.63 Making these changes is also needed to satisfy the requirements in the ADA to serve people in the “most integrated setting,” as decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in its Olmstead decision.

There is no reason for hundreds of individuals on LPS conservatorships to remain stuck in jail and other locked institutions. L.A. County should use the tools and resources necessary to address this illegal and inhumane system.

Appendix A- DRC’s Experts

Elizabeth Jones has expertise in the treatment of people with serious mental disabilities in both institutional and community settings, including those on involuntary holds and conservatorships. Ms. Jones has overseen four mental health institutions, including three public psychiatric hospitals for individuals who were admitted with forensic or civil commitment status, where she worked closely with clinical staff to ensure that people involuntarily committed would be timely discharged to the community with appropriate services. Ms. Jones has consulted and/or served as a monitor in several federal court actions involving the development of community-based services for people with mental disabilities who have been living in institutions. She is currently the Independent Reviewer for a Settlement Agreement between the United States Department of Justice and the State of Georgia, United States v. Georgia, No. 10-249 (ND. Ga.), which requires the development of community-based services for adults at risk of hospitalization in a state psychiatric facility or in the process of being discharged from one. She has previously consulted with DRC regarding community services available for individuals with serious mental disabilities who have experienced psychiatric institutionalization in Alameda County, California, and in the Department of State Hospitals.

Dr. Sam Tsemberis is a clinical-community psychologist who founded Pathways to Housing, Inc., a non-profit organization in New York that originated the Housing First program. Housing First is a highly effective housing and support services model that has been successfully implemented across 300 cities in the United States, as well as internationally. Dr. Tsemberis is the Executive Director of the VA-UCLA Center of Excellence for Training and Research on Veterans Homelessness and Recovery, the CEO of Pathways Housing First Institute and a Clinical Associate Professor with the UCLA Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences. Dr. Tsemberis consults with programs addressing homelessness, mental illness, and addiction across the US and Canada, the EU, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. He has published more than 100 articles and book chapters, and two books on these topics. He has given more than 500 talks and presentations, including a TEDx talk. He has received awards and recognition from SAMHSA, NIMH, the National Alliance to End Homelessness, American Psychiatric Association, American Psychological Association, and the Lieutenant Governor of Canada, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Ottawa, Canda.

- 1. Mercer Health & Benefits LLC, Countywide Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Needs Assessment, at 3 (Aug. 15, 2019), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1064024_BOSReportonAddressingtheShortageofMentalHealthHospitalBeds_Item8_AgendaofJanuary22_2019.pdf#search=%22LPS%22.

- 2. Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code § 5350.

- 3. L.A. County Dep’t of Mental Health (“DMH”), Annual Report on Expanding LPS and Probate Conservatorship Capacity, at 2 (Feb.13, 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1137351_AnnualReporttotheBoardforExpandingLPSandProbateConservatorshipCapacityinLACounty_Item9AgendaofAugust82017_Feb132023-P.pdf#search=%22LPS%22.

- 4. DRC’s authority comes from the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights (“PADD”) Act, 42 U.S.C. § 15041, et seq.; 45 C.F.R. Part 1326, the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness (“PAIMI”) Act, 42 U.S.C. § 10801, et seq.; 42 C.F.R. Part 51, the Protection and Advocacy for Individual Rights (“PAIR”) Act, 29 U.S.C. § 794e; 34 C.F.R. Part 381, and related state laws, Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code (“WIC”) § 4900, et seq.

- 5. Elizabeth Jones has expertise in the treatment of people with serious mental disabilities in both institutional and community settings, including those on involuntary holds and conservatorships.

- 6. Dr. Sam Tsemberis is a clinical-community psychologist who founded Pathways to Housing, Inc., a non-profit organization that originated the Housing First program and works with states in implementing programs to remedy systemic disability discrimination.

- 7. People who have been conserved because they have been determined to be dangerous, often referred to as “Murphy” conservatees after the state senator who introduced the legislation, may only be placed in a secure setting. These individuals make up a small subset of people on LPS conservatorships. In December 2023, only six Murphy conservatees were in the jail awaiting placement. Instead of dismissing charges, Superior Court judges have begun sanctioning the Public Guardian with fines of $1500 per day for failing to place people on Murphy conservatorships.

- 8. California has a duty to provide treatment for individuals found incompetent to stand trial to restore them to competency. If the person is not restored to competency after two years of treatment, the court orders the Public Guardian to investigate a conservatorship. Criminal proceedings are then terminated and the case is often dismissed. See also Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code § 4360(b); Cal. Penal Code § 1615.

- 9. Dr. Christina Ghaly, DHS, and Dr. Lisa Wong, DMH, Addressing the Mental Health Crisis in Los Angeles County: Developing Mental Health Care Facilities to Help Depopulate the Jail Mar 8, 2023,page 28, available from https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1139700_BM-AddressingtheMentalHealthCrisisinLACounty-03.08.23_Signed_.pdf

- 10. The Public Defender is assigned to represent people in conservatorship proceedings.

- 11. Ghaly & Wong, Moving Forward: Expansion Of Secure Mental Health Beds And Development Of Secure Mental Health Facilities To Depopulate The Los Angeles County Jails (January 29, 2024), pg. 3, available from https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1155448_REVISED-MovingForward-ExpansionofSecureMHBedsandDevelopmentofSecureMHFacilitiestoDepopulateLACountyJails_Item24_AgendaofApril4_2023_.pdf

- 12. Conservatorship of Roulet, 23 Cal. 3d 219, 238 (1979) (concurring and dissenting opinion of Clark, J.) A conserved individual “does not face incarceration in a prison but must be placed in a state hospital or some other less restrictive setting.” Conservatorship of Hofferber, 28 Cal. 3d 161, 181-82 (1980).

- 13. People v. Karriker, 149 Cal.App.4th 763, 787-88 (2007).

- 14. See, e.g., Streit v. County of Los Angeles, 236 F.3d 552 (9th Cir. 2001); Williams v. Block, 217 F.3d 848 (9th Cir. 2000). Los Angeles County Sybil Brand Commission for Institutional Inspections, Report & Recommendations on the Los Angeles County Jails Humanitarian Crisis (July 2023), available from https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/185367.pdf.

- 15. Sybil Brand Commission for Inst. Inspections, Report & Recommendations on the Los Angeles County Jails Humanitarian Crisis (July 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/185367.pdf

- 16. L.A. County Sheriff’s Dept., Correctional Services Daily Briefing (Feb. 6, 2024), https://lasd.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Custody_Division_Daily_Briefing_020624. See also Songhai Armstead, Justice, Care, and Opportunities Dept. (“JCOD”), Addressing the Mental Health Crisis in Los Angeles County: Developing Mental Health Care Facilities to Depopulate the Jail, at 2-3 (Mar. 8, 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/173274.pdf (reporting 2022 data). The County’s data is consistent with data reported in 2014 by Dignity and Power, a Los Angeles based grassroots organization, showing that Black people made up 43.7% of those diagnosed with serious mental illness requiring special housing at the jail. See Dignity and Power Now, Impact of Disproportionate Incarceration of and Violence Against Black People with Mental Health Conditions in the World’s Largest Jail System—A Supplementary Submission for the August 2014 United Nations CERD Committee Review of the United States, at 3 (Aug. 2014), https://dignityandpowernow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/CERD_Report_2014.8.pdf

- 17. L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, Custody Services Division Inmate Reception Center Duty Statement re Release of Conserved Inmates, Order 11-07/004.00DS, effective Dec. 18,2023.

- 18. L.A. County Sheriff’s Dept., Correctional Services Daily Briefing (last viewed Feb. 9, 2024), https://lasd.org/transparency/custodyreports/#2024.

- 19. Ghaly & Wong (2024), supra note 11, at 3-4. Some courts are reportedly imposing fines of up to $1500 per day.

- 20. Ghaly & Wong (2024), supra note 11, at 3.

- 21. Cal. Code Regs, tit. 9, § 1810.210.

- 22. DMH, Establishing A Roadmap to Address the Mental Health Bed Shortage: Board of Supervisors Motion Response (Feb. 15, 2024), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1156106_EstablishingARoadmapToAddressTheMentalHealthBedShortage_ItemNo.41-DAgendaOfJanuary242023_-Feb2024.pdf.

- 23. Id. at 2.

- 24. Mercer Health & Benefits, supra note 1, at 62.

- 25. These are Los Angeles General’s Augustus Hawkins Mental Health Center, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, and Olive View-UCLA Medical Center.

- 26. Armstead, supra note 16, at 5. People on conservatorships or temporary conservatorships stay even longer, according to County staff. This is partially due to delays in court hearings for people on temporary conservatorships.

- 27. County staff told the Los Angeles Times that some patients have been at Hawkins for more than two years while awaiting a less restrictive placement. See Ben Poston & Emily Alpert Reyes, Strapped down: Psychiatric patients are restrained at sky-high rates at this L.A. hospital, L.A. Times (Oct. 19, 2023), https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-10-19/psychiatric-patients-restraint-high-rate-california-los-angeles-general-hospital.

- 28. DMH, supra note 3, at Exh. 5; see also Armstead, supra note 16, at 5.

- 29. Dr. Jonathan Sherin, DMH, Addressing the Shortage of Mental Health Hospital Beds, at 6, 18, https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1064024_BOSReportonAddressingtheShortageofMentalHealthHospitalBeds_Item8_AgendaofJanuary22_2019.pdf#search=%22LPS%22; see also Armstead, supra note 16, at 5. The County has 128 inpatient psychiatric beds, with an average length of stay of 75 days, which is 600 patients per year.

- 30. See Poston & Reyes, supra note 26. Long stays increase the likelihood a patient will be restrained. County hospital staff explained to DRC that of the ten patients with highest number of incidents of restraint last year, 70% had been there more than a year.

- 31. See, e.g., Justice in Aging, Racial Disparities in Nursing Facilities—and How to Address Them (2022) (analyzing empirical research relating to racial disparities in nursing facilities and concluding that Black people face an increased likelihood of residing in low-quality facilities and receive comparatively poorer care within those facilities), https://justiceinaging.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Racial-Disparities-in-Nursing-Facilities.pdf.

- 32. See generally DMH, 24 Hour Residential Programs, https://dmh.lacounty.gov/pc/cp/24h/.

- 33. In the past these facilities were described as “Institutions for Mental Disease.” This is a federal Medicaid term, and it refers to any 24/7 treatment facility with more than 16 beds which primarily provides mental health or substance use care. Federal Medicaid does not pay for services provided in IMDs to adults ages 21 to 64. See also Armstead, supra note 16, at 5.

- 34. See DMH, supra note 3. The actual total on the waiting lists is actually much higher, since the 407 people reported on the waiting list for a subacute are only people conserved by the Public Guardian. Hundreds more people with private conservators are likely also on waiting lists.

- 35. Armstead, JCOD report (2023), page 5.

- 36. See DMH, supra note 3.

- 37. Board and care facilities, officially known as licensed Adult Residential Facilities, are privately operated. They are financed primarily through residents’ monthly social security payments of $1,324.82 per month, which is the Nonmedical Out-of-Home Care rate paid to licensed residential facilities. See DMH, Addressing the Board and Care Crisis, at 3 (Jun. 5, 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1143386_ReportResponse-AddressingtheBoardandCareCrisis_Item2AgendaofNovember122019__May2023.pdf.

- 38. DMH’s 2023 Report on expanding LPS conservatorships (footnote 3) lists the number of people on conservatorship in FSPs. DRC interviewed program staff who reported that their clients waited an average of six months to be placed in an FSP.

- 39. 42 C.F.R. § 51.2. Neglect is defined as a negligent act or omission “which placed an individual with mental illness at risk of injury or death.” It includes the failure to “establish or carry out an appropriate individual program or treatment plan (including a discharge plan).” 42 C.F.R. § 51.2. Abuse is defined as a knowing act or failure to act that caused or may have caused injury to an individual with mental illness. 42 C.F.R. § 51.2. This includes a practice “which is likely to cause immediate physical or psychological harm…if such practices continue.” 45 C.F.R. § 1326.19. County officials knowingly hold people in hospitals and subacute facilities when this is not necessary in conditions they know are counter-therapeutic and may cause psychological harm as a result.

- 40. These units in Twin Towers are called “High Observation Units.” See Dr. Christina Ghaly, DHS, Developing A Plan For Closing Men’s Central Jail As Los Angeles County Reduces Its Reliance On Incarceration, at 10, 56 (Mar. 30, 2021), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1104568_DEVELO_1.PDF.

- 41. Ghaly & Wong (2024), supra note 11, at 3.

- 42. The County cost for one day at an acute inpatient psychiatric unit is $1500 per day. Ghaly & Wong (2023),supra note 9, Attach. A, at 2.

- 43. Hospital staff report that Medi-Cal denies approximately 40% of their claims for reimbursement, usually because the patient no longer meets medical criteria for that level of services but remains at the facility because they are awaiting placement in a lower level of care. See also Mercer Health & Benefits, supra note 1, at 45.

- 44. Armstead, supra note 16, at 5.

- 45. With an average length of stay of 75 days, the County’s 128 inpatient psychiatric beds house more than 600 patients per year. The extra two months that patients are held after they are stabilized amounts to $90,000 per person.

- 46. Ghaly & Wong (2023), supra note 9, Attach. A, at 2.

- 47. Ghaly (2021), supra note 40,at 10, 56;see also Ghaly & Wong (2023), supra note 9, Attach. A, at 2.

- 48. Ghaly (2021), supra note 40, at 10, 56; see also Ghaly & Wong (2023), supra note 9, Attach. A, at 2 (estimates of $3499 per month for permanent supported housing and $4272 per month for interim housing); Mercer Health & Benefits, supra note 1, at 16.

- 49. Dr. Lisa Wong, Approval to Amend Existing Legal Entity and 24-Hour Residential Treatment Contracts to Increase their Maximum Contract Amounts for Fiscal Years 2022-23 and 2023-24 for the Continued Provision of Specialty Mental Health Services, at 1-2 (Jun. 6, 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/dmh/1146355_AdoptedBLLE_24HRMCAIncrease.pdf.

- 50. Revised Motion by Supervisor Hilda L. Solis, Approve the Projects and Budgets and Award a Design-Build Contract for the Los Angeles General Medical Center Residential Withdrawal Management Facility and Mental Health Urgent Care Center Projects and Establish the Psychiatric Subacute Facility, at 8, Dec. 19, 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/186898.pdf.

- 51. DMH, supra note 22, at 2.

- 52. Cal. Code Regs. tit. 9 § 3620.05; DMH, MHSA Annual Update: Fiscal Year 2023-2024 (Jun. 6, 2023), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/bc/1152040_e-filedBL12-5-23MHSARevisedAnnualUpdateFY23-24.pdf.

- 53. The Mental Health Services Act requires that local jurisdictions such as Los Angeles follow “the philosophy, principles, and practices of the Recovery Vision for mental health consumers: (1) To promote concepts key to the recovery for individuals who have mental illness: hope, personal empowerment, respect, social connections, self-responsibility, and self-determination. (2) To promote consumer-operated services as a way to support recovery. (3) To reflect the cultural, ethnic, and racial diversity of mental health consumers. (4) To plan for each consumer's individual needs.” Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code § 5813.5(d).

- 54. See Todd P. Gilmer, et al., Fidelity To The Housing First Model And Effectiveness Of Permanent Supported Housing Programs In California, 11 Psychiatric Services at 1311-17 (2014), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25022911/; Todd P. Gilmer, et al., Effect of Full-Service Partnerships on Homelessness, Use and Costs of Mental Health Services, and Quality of Life Among Adults With Serious Mental Illness, 67 Arch Gen Psychiatry (2010), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/210805.

- 55. County of San Diego Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) Plan and Budget, at 24 (Jun. 13, 2023), https://www.sandiegocounty.gov/content/dam/sdc/hhsa/programs/bhs/TRL/MHSA%20Three%20Year%20Plan%20Report%20final.pdf; see id. at 318-328 ( discussing the excellent client outcomes for San Diego’s ACT teams).

- 56. Current funding for each San Diego ACT/FSP Step-Down team is approximately $3.5 million, with enrollment of 119 and 134 people respectively. San Diego also has an ACT/FSP team dedicated to supporting people re-entering the community who are justice-involved.

- 57. See note 54, Gilmer, et al., Fidelity To The Housing First Model at 1311-17 (2014).

- 58. Lisa Wong, et al., Los Angeles County Bed Status Report Update, (Feb. 13, 2024), https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/188529.pdf.

- 59. See DMH, supra note 22, at 1.

- 60. CARE Court is a recently enacted California state law that authorizes certain people “to petition a civil court to create a voluntary CARE agreement or a court-ordered CARE plan that may include treatment, housing resources, and other services for persons with untreated schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.” https://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/CARE-Act-Eligibility-Criteria.pdf. See Cal.Welf. & Inst. Code § 5972 (2023). L.A. County launched its CARE Court program in November 2023.

- 61. Governor Newsom recently signed Senate Bill 43, which expands the definition of grave disability in two important ways: (1) It adds severe substance use disorder as a reason someone could be placed on an involuntary hold; and (2) it adds inability to provide for one’s personal safety or necessary medical care as reasons that a person could be placed on an involuntary hold. SB 43 went into effect on January 1, 2024, except in counties which choose to defer implementation by one or two years. See DRC SB 43 and CARE Court: Community FAQ, https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/publications/sb-43-and-care-court-community-faq.

- 62. DMH, Transforming the Mental Los Angeles County Mental Health System, https://dmh.lacounty.gov/about/lacdmh-strategic-plan-2020-2030/.

- 63. Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code § 5813.5(d).