Porterville Developmental Center Q&A

Porterville Developmental Center Q&A

This explainer has information about Porterville Developmental Center and what it’s like for the people who live there. It also includes statistics about the race and ethnicity of Porterville residents, their length of stay, and troubling data about how often and for how long DDS staff at Porterville put people in manual and mechanical restraints.

This document was originally published in March 2023 and updated to reflect spending in January 2024.

Trigger warning: the following document describes restraint and contains images of equipment used for restraint.

This explainer has information about Porterville Developmental Center and what it’s like for the people who live there. It also includes statistics about the race and ethnicity of Porterville residents, their length of stay, and troubling data about how often and for how long DDS staff at Porterville put people in manual and mechanical restraints.

Who lives at Porterville Developmental Center?

Porterville Developmental Center (PDC) has about 200 residents, who are adults (18 and older) with intellectual and developmental disabilities. These residents are part of the Secure Treatment Program (STP), also referred to as PDC-STP.

In March of 2023, PDC had 186 residents. PDC residents were 91% male and 9% female.

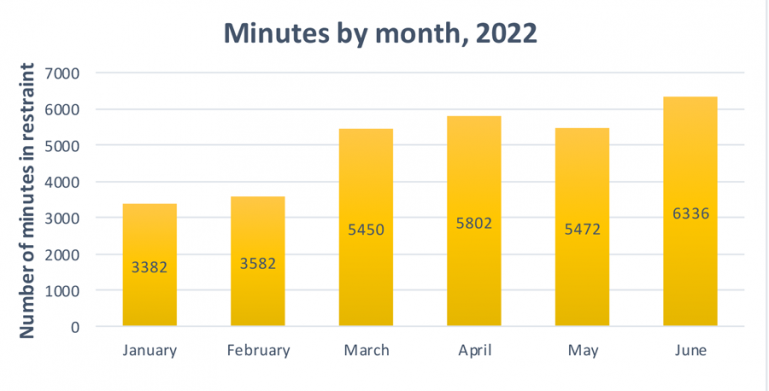

The racial and ethnic demographics of PDC are shown in the following graph.

Figure 1: Race and Ethnicity of PDC Residents, March 2023

How do people end up in Porterville?

People with intellectual and developmental disabilities end up at PDC because they have been charged with a crime but do not understand the nature of the charges against them. This is called being found “incompetent to stand trial.” The person has not been found guilty of committing a crime, but the person is ordered by a court to go to PDC for “treatment,” which includes training to help them understand the criminal legal system and how to assist in their own defense. DDS then agrees to provide this treatment at PDC. This is called "competency restoration training.” Competency restoration training can last for up to 2 years. The rules for this are in Penal Code section 1370.1.

If the person’s “competency to stand trial” is restored, they are returned to court to stand trial for the charges against them. Often, there is a finding that the person’s “competency to stand trial” cannot be restored. When this happens, the person is civilly committed to DDS, and DDS and the regional center recommend that the person should stay at PDC because they are a “danger to themselves or others.” The rules for this are in Welfare and Institutions Code section 6500.

Although the commitment is reviewed annually by a court, it can last for a lifetime, and often lasts longer then the time a person would remain imprisoned. This is because DDS and regional centers do not need to show that a person is currently “dangerous” in order to renew the commitment. They only need to show that the person might be dangerous if released from PDC.

We also know that people end up at PDC because they were never properly assessed for regional center eligibility before they got caught up in the criminal legal system. They were only assessed when it became clear to the court that the person had an intellectual or developmental disability. Spending data also shows that Black and Latinx consumers receive inadequate services from regional centers, which could help deflect them from interactions with law enforcement that lead to involvement with the criminal legal system in the first place.

How long do people stay there?

Some people have short stays and others are there for multiple years. We only have data on how long the current residents have lived at PDC.

Table 1: Length of stay in Porterville Developmental Center of residents in the March 2023 census

| Length of stay in years | Number of residents |

|---|---|

| less than 1 year | 77 |

| 1-4 years | 73 |

| 5-9 years | 20 |

| 10-20 years | 12 |

| over 20 years | 4 |

| Total | 186 |

How much money is spent on PDC?

PDC operation expenditures (actual spending) for FY 2023-2024 $199,052,000, or almost $200 million.1

How is PDC funded?

Porterville Developmental Center Secure Treatment Program (STP) is 100% funded through California’s General Fund. Unlike other DDS programs, the STP is not eligible for federal funding.

How many people work at PDC?

There are 1,358 staff positions at PDC.

- Unit Staffing: 763 staff

- Program Support: 515.5 staff

- Intensive Behavioral Treatment Residence (IBTR): 75.5 staff

- Forensic Team: 4 staff

How much does it cost to detain one person for a year at PDC?

As of June 30, 2023, there are 173 people at PDC at a cost of nearly $200 million. This works out to approximately $1 million per person per year. The maximum capacity of residents is 211 (WIC 7502.5 (a)(2)).

Where do they go when they leave?

DDS established a “step down” model for people leaving PDC as part of prior Safety Net plans. There are three Community Crisis Homes (CCHs) specifically designated as Porterville Step-Down Homes, which are group homes with delayed egress that serve four people each. Often, people transition to Canyon Springs, a DDS-operated institution with over 50 beds that DDS has identified as a re-entry program for people leaving PDC. Some people go into other congregate settings, like enhanced behavioral support homes (EBSHs) or community care facilities. Some people may go directly into their own homes with supported living services. But we believe this outcome is rare because most of the safety net resource development funding is going to building more congregate settings, rather than spending those funds on increasing provider capacity to support people who want to live in their own homes.

We do not have data tracking where people go after leaving PDC. We interviewed people who lived at PDC for several years and then moved into an EBSH for several years.

We have heard from supported living providers and know from our own experience providing legal advocacy to help people leave institutions that this step-down model is not best for everyone. For example, living in close quarters with roommates you did not choose is difficult for anyone. In this case, individuals in smaller congregate settings may have conflicting access needs. At the end of the day, regardless of how good the setup is in another congregate setting, the staff has to accommodate the needs of all the residents, not just one. This is not truly person-centered. If someone moves out of PDC into their own home, then their person-centered supports can adapt to their own unique needs in the community. This is typically done through supported living services, where people receive individualized, wrap-around supports in their own homes.

What is it like there?

As you drive by Porterville Developmental Center, it appears to be a large campus with its own community. There is a fire station, shopping center, recreational hall, and even a pool, which sounds welcoming and community-oriented on paper.

Image from NBC Bay Area: Beating at Porterville Developmental Center Goes Unpunished After Years of Delays – NBC Bay Area

Image from NBC Bay Area: Beating at Porterville Developmental Center Goes Unpunished After Years of Delays – NBC Bay Area

Yet, to enter the Secure Treatment Program, also known there as “Behind the Fence,” you have to store away your phones, electronics, and belongings in your car in order to pass through the metal detector, as a drug detection dog walks by and are screened by the police officers. You are asked to provide them with your CA ID to be reviewed by the Office of Protective Services in exchange for a Visitor Pass.

Visitors must be always accompanied by personnel and are escorted by a golf cart through two sets of chain-link tall gates with razor wire.

The layout of the residential units feels very medicalized, with long hallways with rooms for clients on each side, reminiscent of a psychiatric facility layout. At the center of the unit, there is a staffing station, and there are security cameras in all the halls and common areas. Each unit has a small restraint room with a five-point restraint bed with leather cuffs affixed to the bed. The halls leading up to and inside the restraint room are covered by padding.

This image shows Grafton pads, a type of blocking pads. Image from Mental Health & Healthcare - Amerisewn

This image shows Grafton pads, a type of blocking pads. Image from Mental Health & Healthcare - Amerisewn

Throughout the various common areas, there are two protective body Grafton pads leaning against the wall available for staff to use when residents have certain behaviors. When asked how staff use the pads, a resident explained staff hold up the pad and push residents against the wall or down to the floor. The pads are shaped like a shield and have straps on the inside for easy grip. The pads are large enough to cover the staff’s torso and face. The way the resident described the use of the blocking pads is similar to how police use riot shields.

This image is an example of a bed used for mechanical restraint, specifically five-point restraint. Image from a training given to PDC staff.

This image is an example of a bed used for mechanical restraint, specifically five-point restraint. Image from a training given to PDC staff.

What is restraint and how is it used?

PDC uses multiple types of restraint. Manual restraint is when a staff person holds onto a resident. Mechanical restraint uses a device to restrict a resident’s movement, like strapping arms and legs onto a bed. Sometimes a mesh spit hood is placed over the head of the resident while in mechanical restraint. Manual restraints can last up to 5 minutes, and mechanical restraints can last longer.

Our investigations unit has been interviewing PDC residents about restraint. They found that every person they interviewed who was restrained for over 2 hours was Black or Latinx. We have historically not received race and ethnicity restraint data from DDS. After requesting this information directly from PDC, we recently received race and ethnicity data for a three-month period. We appreciate and encourage DDS to collect and publish this information in its efforts to address racial disparities. From our initial assessment, people of color, particularly Black and Latinx people, are restrained more often and for longer than white people.

How often is restraint used?

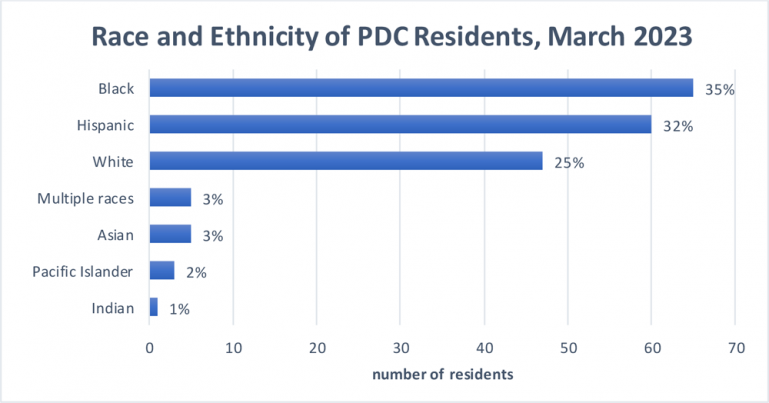

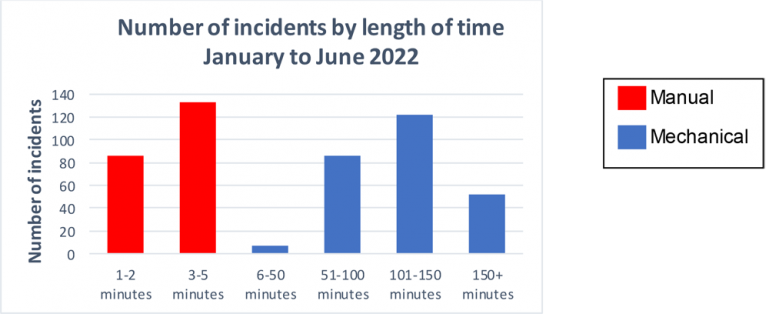

The following graphs show restraint data from the first 6 months of 2022. DDS is required to share this data, which we at DRC analyzed to produce these figures.

Figure 2: Number of restraint incidents by length of time in restraint, January - June 2022

In all restraint incidents, about half (46%) are manual and about half (54%) are mechanical. Mechanical restraints can last much longer than manual. Therefore, when you look at the total minutes spent in restraint, 98% of those minutes are spent in mechanical restraints.

These two graphs show the number of restraint incidents and the sum of the minutes of those incidents for each month in the first half of 2022.

Figure 3: Incidents of restraint by month, January - June 2022

Figure 4: Minutes in restraint by month, January - June 2022