Abuse/Neglect Investigation and Request for Corrective Action San Joaquin County’s Use of Solitary Confinement and Mental Health System

Abuse/Neglect Investigation and Request for Corrective Action San Joaquin County’s Use of Solitary Confinement and Mental Health System

Disability Rights California (“DRC”) has been investigating San Joaquin County’s (“the County”) jail system pursuant to its authority as California’s protection and advocacy system for people with disabilities. For purposes of this investigation, DRC has designated the Prison Law Office (“PLO”) as its authorized agent.

Captain Samuel Cortez

Captain Kim De La Cruz

Lt. Steve Martinez

San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office

7000 Michael Canlis Blvd

French Camp, CA 95231

RE: Abuse/Neglect Investigation and Request for Corrective Action San Joaquin County’s Use of Solitary Confinement and Mental Health System

Dear Captain Cortez, Captain De La Cruz, and Lt. Martinez:

Disability Rights California (“DRC”) has been investigating San Joaquin County’s (“the County”) jail system pursuant to its authority as California’s protection and advocacy system for people with disabilities. For purposes of this investigation, DRC has designated the Prison Law Office (“PLO”) as its authorized agent. At this stage, the investigation focuses on the use of segregation – also known as solitary confinement – and the treatment of people with disabilities as relates to these practices.

On December 14, 2022, DRC and PLO teams visited the County’s Jail Core and South Jail facilities. We toured both facilities, interviewed dozens of incarcerated individuals, and met with jail leadership, including with representatives from custody, medical and mental health care, programming, and other departments.

We would like to thank the Sheriff’s Office and Correctional Health Care (“CHC”) leadership and staff for their hospitality. The tour went smoothly, and staff assisted us in accessing all places and people we requested, in answering questions, and in engaging in productive dialogue. We were grateful that staff respected incarcerated people’s confidentiality and made significant efforts to ensure that we could speak to whomever we needed with sufficient sound privacy. We appreciate the cooperation and professionalism in this regard.

As we discussed at the close of our visit, we believe many of San Joaquin’s practices require significant reform. In any correctional setting, segregation should be used only as a last resort, when no less restrictive intervention would be sufficient. San Joaquin overuses segregation and disciplinary isolation, in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments and the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”).

Based on our investigation, we have concluded that there is probable cause to find that abuse and/or neglect of people with disabilities has or may have occurred, as those terms are defined in DRC’s authorizing statutes and regulations.1 These authorizing statutes and regulations allow DRC, and PLO as its authorized agent, to take next steps in an investigation, including accessing documents, facility premises, and incarcerated people.

At the end of our visit, we shared a summary of our concerns, which we discuss further below. In Section I, we provide a brief description of San Joaquin’s system of segregation, as we understand it, as a backdrop to our findings. In Section II, we document our findings in more detail. In Section III, we lay out some critical practices for segregation in a county jail system, which should be the principles on which San Joaquin bases its remedial measures.

In light of our respect for jail leadership and staff, we are hopeful that we can work cooperatively with you in this process, to implement meaningful reforms that bring the jail system’s use of segregation into alignment with acceptable practices. We have found this cooperative approach to be very productive in our work with other counties and to offer the opportunity for meaningful and potentially long-lasting change that benefits all stakeholders. For example, we recently met with San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office about our concerns regarding segregation practices at their jail, following a site visit and findings letter. San Mateo County has already implemented substantial reforms in response to our visit and letter and has committed to additional policy revisions which we believe have the potential to make San Mateo a leader statewide. We hope we can engage in equally productive and cooperative dialogue with the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office.

I. Background: San Joaquin’s System of Segregation

To gain an understanding of San Joaquin’s practices, we requested documents through a Public Records Act (“PRA”) Request, reviewed those documents as well as BSCC reports, and spoke with leadership staff on site about the basic system of segregation in the jail. We learned the following:

The County’s jail system has a total bed capacity of 1,550, according to the BSCC.2 The Jail Core building contains the Medical unit, the Sheltered Housing unit, and the Intake section. The Medical Unit (also referred to as “SOMED”) has a capacity of 40 and houses individuals who have acute medical and/or psychiatric needs. The Sheltered Housing unit has a capacity of 100 and houses individuals who require ongoing medical non-acute care. Intake includes booking, transportation, and quarantine/isolation cells. One intake unit houses individuals who are participants in the Jail Based Competency Treatment unit, as contracted with the Department of State Hospitals. This unit’s capacity is 12.

The South Jail building has eight units; six units are general population housing, and two are administrative segregation and disciplinary isolation pods. People in administrative segregation and disciplinary isolation are housed together in Pods 7 and 8 (“AS7” and “AS8”), with a combined bed capacity of 188. AS7 is designated for men, whereas AS8 is designated as “co-ed.” Individuals serving discipline are also housed in AS7 and AS8. Both units have single and double cells.

In response to our PRA Request, San Joaquin reported that, as of July 1, 2022, it detained 1,244 people in the entire jail system (80.3% of capacity). Approximately 134 people were in AS7 and AS8 (71.3% of capacity), and of the people housed there, approximately half were serving disciplinary terms (approximately 65 people). Sixty-four individuals were in sheltered living (64.6% of capacity) and 27 were in medical housing (67.5% of capacity).

For purposes of this investigation, we define segregation as circumstances in which a person is confined in their cell, alone or with others, for a substantially longer period of time each day than those in general population – no matter the reason the person is in this unit or the number of days they spend there. As explained below, given the substantial restriction on out-of-cell time in Administrative Segregation/Disciplinary Isolation and Medical and Sheltered Living pods, these pods clearly constitute segregation.

II. Initial Findings

Generally, when our offices evaluate a jail system’s use of segregation, we look at five key areas: (1) who goes into segregation; (2) how long they stay; (3) how they get out; (4) the conditions while they are there; and (5) program-rich alternatives to segregation, especially for people with serious mental health needs. In each of these areas, San Joaquin’s practices require significant work. As it stands, San Joaquin’s system of segregation is unconstitutional and violates the ADA.

The San Joaquin Jail places people with serious mental illness in segregation in AS7 and AS8, often for behavior that appears to be a manifestation of their disability.3 They remain in segregation for months and even years at a time, with no upper limit on how long they can remain and no instruction on what they can do to get out of segregation. People with disabilities have minimal to no meaningful out-of-cell time or human interaction, and have few to no activities to relieve their sensory deprivation. Such conditions clearly exacerbate mental illness and risk decompensation. This overreliance on segregation means the County fails to provide treatment for people experiencing mental health crises, and that its segregation practices exacerbate existing mental health conditions. Finally, San Joaquin fails to provide any meaningful, program-rich alternatives to segregation for people with serious mental health needs.

A. Placement in Segregation: San Joaquin Effectively Warehouses People with Serious Mental Health Needs in Segregation.

Placing a person with mental illness in prolonged segregation is unconstitutional. It is also clearly deleterious to their mental health; countless studies and scholarly articles have enumerated the ways in which segregation leads to decompensation and causes or exacerbates mental health conditions.4

By the County’s own admission, it places people with serious mental health disabilities in prolonged segregation–including Administrative Segregation, Disciplinary Isolation, Medical and Sheltered Housing. On site, the County provided us population lists for people in each of these units and marked those who had mental health conditions it labeled as “Serious Mental Illness” (“SMI”). For example, in AS7, the County’s list shows that 28 people are recognized by the County as having SMI. In AS8, the County’s list shows that 22 people are recognized as having SMI. This means that approximately one-third of individuals in non-medical and non-psychiatric segregation had SMI.

We have reason to believe the numbers of people with serious mental health disabilities who are subjected to prolonged segregation is even higher than what is reflected in the County’s population lists. In our interviews, many of the people we spoke to described witnessing others exhibiting, or themselves experiencing, symptoms of serious mental illness; they described active delusions, paranoia, and self-harm behaviors. For example, one person in AS8 told us that he had serious mental needs and was receiving psychiatric medication for it, and CHC confirmed both these facts for us; however, he was not listed as “SMI” on the County’s AS8 list. It is clear from both our interviews and the County’s own records that people with serious mental health needs are effectively being warehoused in segregation, exacerbating their conditions and depriving them of meaningful mental health services.

i. Administrative Segregation & Disciplinary Isolation

The County’s practice for determining whether to place someone with a mental health disability into administrative segregation and/or disciplinary isolation raises concerns. In AS7 and AS8, it appears that the underlying behavior that results in placement in these units is often related to or caused by the individual’s disabilities. The County appears to lack a formal process to identify behaviors that result from a disability and to determine what the appropriate, non-discriminatory, non-disciplinary response to these symptoms should be. When we spoke to staff, we learned that there is an informal practice of custody notifying medical staff when individuals are moved to these units, but we could not identify a formal protocol for evaluating whether a move to AS7 or AS8 is appropriate in light of a person’s mental health conditions. Specifically, the County did not point us to any policy or practice that requires an evaluation by mental health staff of whether the behavior at issue resulted from or should be mitigated by the person’s disability; whether the person understands their behavior or can understand a punitive sanction; or whether placement in segregation will exacerbate the person’s mental health condition. Further, there appears to be no multidisciplinary committee or other similar group that addresses recurrent behaviors that result in discipline or administrative housing placements and explores alternatives to segregation for these individuals.

The County’s practices for determining whether to end disciplinary isolation and administrative segregation for individuals also raises concerns. Jail leadership stated that individuals serving discipline terms are not “immediately” released from AS7/AS8 once their term has ended. Instead, jail staff interview these individuals “face-to-face” to “determine if a person is ready.” Leadership stated that if individuals are rude or unwilling to interact, they will keep an individual in AS7/AS8 until they are more amenable. Jail staff did not indicate any formal policy that specifies what particular behavior results in “staying” in segregation beyond the predetermined disciplinary term, or how it is decided that a person should be moved from a non-disciplinary administrative segregation term back into general population.

ii. Medical & Sheltered Housing

In Medical and Sheltered Housing units, we spoke with multiple individuals who need ongoing acute care who, because of their medical needs, are effectively in segregation. One individual was on dialysis and had neuropathy: those medical conditions should not result in a person being placed in conditions of segregation. Another person—who sat in his cell for long periods of time with a blanket over his head due to cold temperatures—explained that he has arthritis and nerve damage from a stroke, and that he is prohibited from doing the necessary exercises to improve his condition because he is only allowed out of his cell once per day. A number of the people we spoke to in the Medical Housing unit had acute psychiatric needs and were nevertheless living in conditions of segregation. For instance, one person explained how he has mental health challenges and, because of being isolated in his medical cell, he sometimes feels suicidal but is unable to see a doctor. None of these people should have been held in segregated conditions.

It was unclear to us why some people were in the Sheltered Housing unit, which similarly had restricted out-of-cell time and amounted to conditions of segregation. For example, one person we spoke to in Sheltered Housing is a deaf person who does not speak. While we attempted to interview them using written notes, it appeared they do not read or write easily.5 Although we are not fluent in sign language, by signing the alphabet, we were able to communicate very minimally. The individual told us they did not know why they were in that unit; the main thing they wanted was a sign language interpreter. Both from our communications with this individual and with jail staff and leadership afterward, it was unclear what services and accommodations this individual was getting in sheltered housing or why they needed to be there. Since our monitoring visit, DRC has received intakes from other individuals who are also similarly being held in segregation and need sign language interpreters. We address related ADA accommodation issues further below.

Quite obviously, a person’s physical or mental health disability should not be the reason for their placement in segregation. We set forth principles for exclusion of vulnerable populations, mental health assessments prior to placement, and mental health checks during segregation in Sections III.A and Section III.D below. We hope that we can work on these new protocols together with jail leadership and CHC.

B. Lengths of Stay in Segregation: San Joaquin Keeps People in Segregation for Unnecessarily Lengthy Terms and Has an Impermissibly Vague Disciplinary System.

i. Extra-Long Terms

Given the conditions in these units, we are very concerned by how long some people remain in administrative segregation and/or disciplinary isolation. As a result of our records request, we learned that as of July 1, 2022, two individuals had been in AS7 or AS8 for over two years. Eight individuals had been there for one to two years; 19 individuals had been there between 180 days and one year, and 61 individuals had been there between 30 and 180 days. In sheltered housing, one individual had been there for over one year; ten had been there between 180 days and one year; and 26 had been there between 30 days and 180 days:

| Length in Stay in Administrative Segregation | Number of individuals | Length in Stay in Sheltered Housing | Number of individuals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over two years | 2 | Over two years | 0 |

| One to two years | 8 | One to two years | 1 |

| 180 days to one year | 19 | 180 days to one year | 10 |

| 30 days to 180 days | 61 | 30 days to 180 days | 26 |

Based on our conversation with leadership, there is no upper limit on how long a person can stay in segregated housing—whether medical, sheltered, administrative segregation, disciplinary isolation, or some combination. Jail leadership told us that the maximum consecutive disciplinary terms is unlimited, and individuals can serve up to 30 days initially and then in 15 day increments thereafter, with a 72-hour break in between discipline terms.

In Medical and Sheltered Housing, individuals seem to remain in these units as long as their medical conditions or other vulnerabilities continue. When we interviewed individuals in these units, they reported that they were unable to get necessary medical and/or mental health care that would allow them to be in a less-confined housing setting.

Finally, the County offers no “step-down” process from any of the segregation units, which would allow people to move from highly restrictive settings to less restrictive conditions and prepare for a return to general population or release to community after such lengthy terms.

ii. Vague and Overly Discretionary Discipline System

The County’s process for determining whether and for how long individuals are placed in disciplinary detention is highly discretionary and raises significant concerns. First, the County does not use a disciplinary matrix to apply discipline fairly and equitably. As a result, the disciplinary system relies on staff discretion to mete out, initiate, and end discipline. Second, the County does not determine whether certain behaviors merit discipline at all and, relatedly, whether certain behaviors are related to or symptoms of disabilities. Third, the discipline system does not account for days in detention prior to the hearing or the actual length of discipline. We spoke with incarcerated people who told us that they were in administrative segregation pending their disciplinary hearing, served their discipline sentence, and remained in administrative segregation after their term ended.

San Joaquin must change its approach to discipline, including limiting the types of behavior that are disciplined with segregation, ensuring due process and fairness throughout the process, shortening disciplinary terms, and setting upper limits on the number of consecutive days a person can remain in disciplinary isolation and administrative housing, as well as the total number of non-consecutive days a person can be placed in these units over a period of months. The current practices do not meet the necessary standards, which we outline in Section III.B.

C. Removal from Segregation: San Joaquin Lacks a Transparent, Objective System for Imposing and Then Ending Segregation, Which Keeps Individuals in Segregation Unnecessarily.

The County’s process for determining when individuals can be released from segregation is also highly discretionary and raises significant concerns. During our monitoring visit, jail leadership informed us that, for the purpose of release from administrative segregation, a classification officer conducts weekly computer reviews and in-depth face-to-face interviews with segregated individuals every thirty days. However, the criteria used to determine whether someone can be denied release from segregation is highly subjective and amorphous. According to jail leadership, classification officers may consider factors such as an incarcerated person’s behavior, prior incidents, whether a person talks back to the classification officer, or simply if an officer thinks the person “isn’t being honest.” In other words, even a wrong statement or a wrong look can be used to justify denying release from segregation.

The broad discretion afforded to classification officers in assessing when someone can be released from administrative segregation is particularly harmful to incarcerated individuals with mental health disabilities. Because prolonged isolation often exacerbates an individual’s mental health symptoms, these individuals may have particular difficulties presenting during their monthly reviews. Consequently, incarcerated individuals with mental health disabilities may be penalized further by being denied release from segregation unnecessarily.

In terms of disciplinary segregation, there does not appear to be any clear jail policy or practice limiting the number of consecutive terms that can be imposed. Jail staff and incarcerated people with whom we spoke did not appear aware of any upper limit on the number of times a disciplinary term could be continued. Some people we spoke to knew when their discipline term would be or had been completed but did not know when they would leave segregation in fact. Indeed, at least one person told us his disciplinary term had been completed two days prior, but he remained in AS8 without explanation. Others we spoke to did not know when their disciplinary term would end or what to do to be removed.

The ambiguity over when and how someone is released from segregation is exacerbated by the fact that little to no information is provided to incarcerated people about the classification process, and there is a widespread culture of fear. We interviewed individuals in segregated housing who not only expressed confusion about why they were there, but also how to challenge their placement and what they could do to get out. Some on disciplinary isolation reported that they did not get to participate in their disciplinary hearing or challenge their placement. Some in administrative segregation stated that they had “always” been in administrative segregation and did not know how to address their custody classification level. Moreover, some people seemed confused about whether they were even serving a disciplinary term or were in administrative segregation for a non-disciplinary reason. When we asked incarcerated individuals who were being held in segregation whether they filed inmate requests or grievances about their placement in segregation, numerous individuals throughout the segregated housing units expressed (1) that they had no easy access to these forms—such as being freely available in the common space or on tablets; and (2) that they were afraid of retaliation from custody staff if they raised any concerns.

As set forth in Sections III.A and III.C, the County must develop clear criteria and strategies to minimize the overreliance on restrictive conditions in administrative segregation and disciplinary isolation. It must also develop a process to ensure that it does not punish individuals with disabilities for behavior stemming from their disability, in which medical and mental health leadership should play an active role. We hope we can work on these efforts together.

D. Conditions in Segregation: San Joaquin Offers Little to No Activity, Mental Health Treatment, or Pro-Social Interaction in Segregation.

Conditions in the segregation units we visited raised significant concerns, including: (1) limited out-of-cell time; (2) lack of recreation equipment in the “outside” yard; (3) lack of games, activities or programming in the dayroom; (4) unhygienic cells with limited access to tablets and other forms of entertainment; (5) limited to no engagement with other individuals; (6) lack of confidential meetings with mental health clinicians; (7) significant physical plant issues that do not comply with the requirements in the Americans with Disabilities Act; and (8) the lack of an ADA coordinator to respond to the reasonable accommodation needs of individuals with disabilities. Accordingly, many individuals, including individuals with disabilities, languish with little to no activities to mitigate their sensory deprivation. One of the most extreme examples of solitary confinement we observed during our inspection involved an individual who had been in an observation cell in Medical Housing for days, with the lights on 24 hours a day, with no out-of-cell time or access to a shower. The individual reported that his condition was deteriorating due to these conditions.

The County’s segregated housing units have limited out-of-cell time. In AS7 and AS8, staff told us that everyone is offered approximately 1.5 hours of out-of-cell time every day, meaning that people in administrative housing spend more than 22 hours in their cell each day. Jail leadership and people we interviewed both reported that many individuals refuse out-of-cell time, even though this is the only time when people are able to shower or make phone calls to loved ones or legal counsel. People we spoke to explained that this was because it was offered at a time of day the person did not want to be out—such as 5:00 a.m.—and/or because there is little to do during on the exercise yard and in the dayroom. Because people with classification Level 8 are required to take their out-of-cell time alone, the system relies on refusals. Indeed, staff explained to us that it was not possible mathematically to have everyone take their 1.5 hours out per day without some refusals. This means that, functionally, many individuals never leave their cells.

In AS7 and AS8, individuals are able to get “outside” recreation. There is no recreation equipment in the all-concrete yards. Because so many people have to be let out in a 24-hour period, and some people are offered recreation only early in the morning, at 4:30 a.m. or 5:00 a.m., when there is no sunlight or warmth. This is particularly concerning for individuals with disabilities who may be unable to do outdoor recreation or other out-of-cell programming at any time of day due to medical conditions. In most units at the jail, jail leadership told us people had access to a recreation yard. However, the yard is a concrete box with no equipment. While individuals can see the sky from the yard, they told us it only gets direct sunlight for a limited time each day, and so some people never get dayroom where they can experience sunlight.

AS7/8 recreation yards

AS7/8 recreation yards

When people are allowed out of their cells, there is little to occupy their senses: we saw no games, tables, recreation equipment, or other activities available to people in the tier or dayroom spaces. During our visit, we did not hear of any groups or programming in AS7 and AS8, such as group therapy, substance abuse classes, or educational classes.

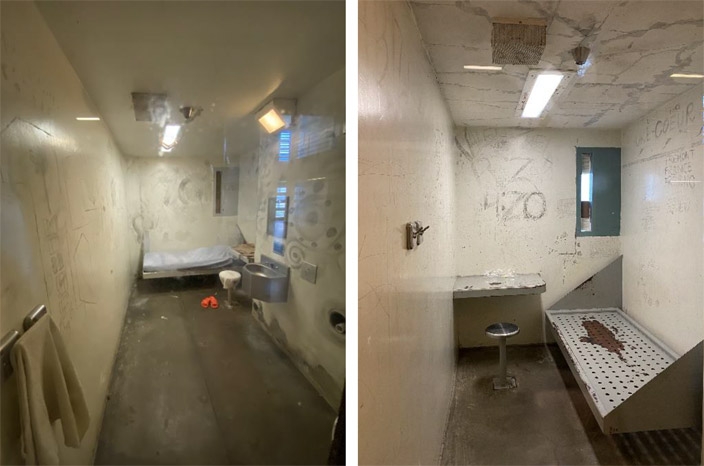

Photo Left: Administrative Segregation / Disciplinary Isolation

Photo Left: Administrative Segregation / Disciplinary Isolation

Photo Right: Dayroom/Tier Space with debris and open trash bags

The cells in which people spend more than 22 hours each day appeared unhygienic, as though they had not been cleaned for long periods of time. Some individuals stated that the cells had not been cleaned before they moved into them. We documented and saw old food waste, wrappers, and other debris in the dayroom/tier-space, showers, and cells throughout AS7 and AS8. Many individuals in these units are double-bunked. These cells are quite small and very crowded, with a bunk bed, one small desk/writing area for both people, and one small toilet commode beside the bed. There is only space for one individual to ambulate around the cell at a time. Some of the showers we observed in these units had various trash items and grime built up.

Administrative Segregation / Disciplinary Isolation Cells

Administrative Segregation / Disciplinary Isolation Cells

Inside a person’s administrative segregation cell, there is little to occupy the time or to engage the senses. Jail leadership stated that they had recently started a tablet program. However, the jail prohibits individuals serving disciplinary terms from having tablets. Notably, these individuals would likely benefit most from having tablets, as they have no other programming or stimulation. We heard that individuals rarely get to select books to read.

In Medical and Sheltered Living units, we observed conditions similar to Administrative Segregation and Disciplinary Isolation: filthy cells, limited out-of-cell time, limited to no programming options, limited access to tablets and other forms of entertainment, and limited to no engagement with other individuals.

In all forms of segregated housing, people with serious mental illness reported that they rarely had confidential meetings with their mental health clinicians. In AS7 and AS8, there are rooms labeled as “Mental Health Interview”6 on the ground floor, but we did not speak to individuals who had received treatment or spoke with a mental health clinician in those rooms.

The outside and inside of a “Mental Health Interview” Room

The outside and inside of a “Mental Health Interview” Room

We understand that almost all providers see patients cell side within earshot of other staff and incarcerated people. Confidentiality is the cornerstone of health care, and mental health appointments are less likely to be therapeutically effective when a patient is inhibited from sharing all pertinent information. Although segregation rounds may supplement other care plans, it is not clinically appropriate to conduct mental health evaluations or provide mental health services cell-side. In addition, many people expressed concerns about quality of treatment they received. They told us that mental health staff only provided them puzzles or crosswords and did not engage them in any meaningful interaction.

Throughout our tour, we noted significant physical plant issues that did not comply with the requirements in the Americans with Disabilities Act. For example, some shower stalls had physical barriers that required individuals to be able to “step up” to the shower. Even the “ADA shower” contained a lip that may present a fall risk or otherwise be difficult to navigate with a mobility disability. Some units lacked shower chairs. None of the showers in AS7 or AS8 were large enough to accommodate wheelchairs. In Medical Housing, the phone area had no permanent, accessible seating option, and the phones were difficult or impossible to use for some individuals, due to their disabilities.

Left Photo: Non-ADA Shower in AS7 with trash

Left Photo: Non-ADA Shower in AS7 with trash

Right Photo: Inaccessible Phones in Medical Housing

Notably, the jail lacks an ADA coordinator. The jail lacked a process to identify and track individuals with disabilities, especially individuals who have disabilities that impact their mobility, hearing, seeing, or other ambulatory or sensory skills. We interviewed individuals who had mobility issues who were on the second floor and expressed concerns for their own safety when going down the stairs. As described above, we also interviewed a person who is deaf and does not speak who did not appear to be getting any accommodations. We repeatedly asked jail leadership about this individual throughout the day and understand that no medical staff sign. Unfortunately, by the end of the day, we still did not have an answer as to whether anyone on site does or could provide sign language interpretation.

These conditions of segregation must be remedied as a matter of urgency. We outline principles for remedial measures related to conditions in Section III.D.

E. Alternatives to Segregation for People with Serious Mental Health Needs: San Joaquin Must Reduce its Reliance on Segregation by Focusing on Program-Rich Alternatives and Decarceration and Diversion.

The County’s resources and programming for individuals with mental health conditions are insufficient to meet the wide range of needs, from acute services and care to mitigation and treatment. Notably, the County lacks a comprehensive behavioral health treatment program. The County also lacks adequate procedures to identify and manage individuals who are experiencing suicidality. During our exit meeting, the County agreed that they should adopt an objective criteria (e.g., the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)) to assess and take appropriate interventions to support patients. We appreciate the County’s quick thinking to address this issue, and we look forward to learning more about its implementation.

More broadly, we urge the County to consider taking concerted action to reduce the size of the jail population and, in particular, the number of people with disabilities generally and people with mental health conditions specifically in custody. We encourage the County to consider alternatives to incarceration, opportunities for release, and diversion mechanisms to reduce the number of people who require mental health treatment in the jails. Sacramento County recently has taken action to substantially reduce the number of people in custody to address longstanding deficiencies in restrictive housing practices and the provision of mental health care, among other things. Santa Clara County also has recently embarked on a program to reduce the number of people incarcerated in its jails. We encourage the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office to consider decarcerative strategies and to begin such discussions in partnership with patrol, prosecutors, San Joaquin County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services, and the Board of Supervisors, as appropriate. We address each of these recommendations, among others, in Section III.E below.

III. Practices and Principles for Remedial Measures

San Joaquin should undertake remedial measures to substantially reform its use of segregation and to ensure people with serious mental health needs are provided program-rich alternatives. In addition to the specific recommendations described above, the following practices and principles should be incorporated in order to address the violations of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments and the ADA, and to protect individual with disabilities from further abuse and neglect. Some of these principles are reflected in county jail policies throughout the state or in other state systems, including, as discussed on site, in Santa Clara and Sacramento. While these principles are not exhaustive, we hope they provide a helpful framework for our subsequent discussions.

We look forward to working with you to operationalize these principles into discrete policies and procedures to meet San Joaquin specific needs and to remedy the issues we have identified in Section II.

A. Placement in Segregation

In every case, segregation should be used only as a last resort, when no less restrictive intervention would be sufficient.

Generally speaking, it is acceptable to separate individuals for short periods of time as necessary for safety and security, but the use of isolation should be avoided. Isolation should be used only as absolutely necessary, for the shortest period of time possible, and subject to strict time limits. Segregation for administrative or management reasons should be used only when the person exhibits real threats of violence based on behavior and conduct, and the risk of violence is imminent and ongoing. Segregation should not be used in response to merely antisocial, disrespectful or behaviorally challenging conduct toward jail staff or others.

Insofar as segregation is used as a short-term disciplinary measure, it should be used only in response to acts of serious violence. It should be accompanied by a clear disciplinary matrix, or schedule of sanctions, that specifies that only certain violent acts may be disciplined with a short period of segregation. The jail should always consider non-segregation sanctions first, such as the loss of other privileges. As an essential component of any discipline program, the jail must establish a robust procedure for ensuring that people are not disciplined for behavior that results from their mental, intellectual or developmental disabilities, and that mental health considerations are taken into account as mitigation and in assessing the appropriateness of any punitive sanction.

The following are core principles with respect to placement of people in segregation:

- Exclusion of Vulnerable Populations. Some people should never be placed in segregation, including but not limited to: o People with mental or physical disabilities;

- People with other serious medical conditions that cannot be adequately treated in or are otherwise contraindicated with segregation;

- People who are pregnant, in post-partum recovery, or who have recently suffered a miscarriage or terminated a pregnancy;

- People who are younger than a certain age or older than a certain age (we recommend under age 25 and over age 60).

- Mental Health Assessments Before Placement. Every person placed in segregation should undergo documented mental health screenings prior to placement in segregation in order to ensure no contraindications to segregation (including but not limited to membership in a vulnerable population, as described above) and establish a baseline of health against which to compare any deterioration or decompensation. Assessments should occur in a private and confidential setting.

- Evidence for Placement in Segregation and Related Process Protections. Placement in segregation should be supported by significant, verified evidence and accompanied by related process protections. o The jail bears the burden of proof.

- Placement should not be based solely on confidential information considered by jail staff but not provided to the incarcerated person.

- The incarcerated person should have fair and meaningful opportunities to contest the placement, including the right to an initial hearing within 72 hours and process protections at that hearing.

- Administrative Segregation/Protective Custody. People should not be placed in segregation for their own protection. o A person who is LGBTQI, who is a so-called gang drop-out, or whose crime is notorious should not be placed in segregation for that reason only. Instead, people requiring protection should be transferred to a more appropriate custody unit that ensures full access to out-of-cell time, programming, and other services available to the rest of the incarcerated population.

- People who are active in gangs or who have keep-separates should not be placed in segregation for that reason alone, unless such affiliations result in violence requiring segregation for disciplinary or administrative and management reasons as outlined above.

B. Lengths of Stay in Segregation

- Maximum Consecutive Days. There must be a maximum number of consecutive days a person can remain in segregation. We recommend 15 days at maximum, as supported by international standards (see United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules).

- Maximum Non-Consecutive Days. There must be a maximum number of non-consecutive days a person can remain in segregation during a certain months-long period. We recommend 45 total days in a 180-day period at maximum. Multiple months of segregation, separated by one or several day “breaks,” is impermissible.

C. Removal from Segregation

- Regular Reviews. Reviews should be conducted regularly at set intervals to assess the ongoing need for segregation, with face-to-face participation by the incarcerated person. These reviews should be documented.

- Criteria for Removal. People in segregation and Classification staff should be provided written criteria for removal from segregation, and grievances or “inmate slips/inquiries” must be made available so that individuals can raise concerns about over-long terms in segregation as appropriate.

- Step Down and Reintegration in General Population. Mental health staff and other programming staff, as appropriate, should provide step-down services for people being released from segregation to general population, such as additional therapeutic and clinical supports after release, to assist in reintegration and additional property privileges and increased out-of-cell time in the final days of segregation.

- Release to Community. The jail should endeavor to ensure people are not released directly from segregation into the community and utilize step-down or alternative housing arrangements where possible.

D. Conditions in Segregation

- Out-of-Cell Time. There must be certain minimum conditions regarding hours, space, activities, and social interaction. o Hours. People in segregation cannot be isolated for 24 hours per day and require a minimum number of hours out-of-cell per day. As a best practice, we recommend four hours of out-of-cell time in segregation units.7 Out-of-cell time should be documented in daily logs.

- Space. Out-of-cell time can occur in a combination of dayroom, recreation yard, and/or program office or classroom if such office or classroom is the site of programming in which the person participates.

- Out-of-cell time should not be limited to the space of a tier only (i.e., the space outside cells).

- The space must be sufficiently large to allow opportunities for movement and activity.

- Out-of-cell time cannot occur in a cage or similar module.

- Individuals should be offered outdoor recreation on rotating schedules to ensure equitable access to outdoor space, and the times offered should be during normal waking hours.

- Activities. Some or all of the out-of-cell time should involve the opportunity to engage in activities that involve sensory and physical stimulation.

- This may include TV and other entertainment, physical exercise and recreation equipment, cards, art, games, individual or group programming, and/or educational opportunities.

- The activities may be self-directed or jail-facilitated but must offer opportunities to do more than simply walk, stand, or sit in the out-of-cell space, should the person wish.

- Social Interaction. Out-of-cell activities must provide the opportunity for social interaction with other incarcerated people beyond a person’s cellmate.

- Space. Out-of-cell time can occur in a combination of dayroom, recreation yard, and/or program office or classroom if such office or classroom is the site of programming in which the person participates.

- In-Cell Opportunities for Sensory Stimulation. People in segregation should retain all other privileges of the incarcerated population, unless a loss of privileges is imposed as the result of concurrent discipline, including access to books and other reading and writing instruments, commissary items, and radios, tablets and any other devices permitted in general population.

- Mental Health Checks. A qualified mental health professional should meet with the person in segregation regularly, no less than once weekly, to assess and document their health status and make referrals as necessary. If mental health staff believe a person’s continued placement in segregation is substantially affecting their health condition, they may recommend removal from segregation.

- Confidential Medical and Mental Health Visits. The jail should provide space for confidential medical and mental health appointments and the presumption should be that all appointments occur in these confidential settings unless the individual refuses or specific, individualized safety and security concerns are documented.

- Suicidality Identification and Procedures. The County should adopt the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) or other professional tool to support clinicians and staff.

- Custody Checks. Custody staff should perform checks multiple times per day (up to every half hour). If the person demonstrates unusual behavior or indicates suicidality or self-harm, custody should notify mental health and checks should be increased to every 15 minutes or to constant watch.

- Cleanliness. Segregation cells should be routinely cleaned, including before and after a person is moved into or out of them and whenever the need is identified by custody, medical or mental health staff during visual observations of the cell.

- ADA Compliance. The built infrastructure and physical plant of the jail, including cells, programming rooms, outdoor recreation, showers and toilets, must be accessible to individuals with disabilities and modifications must be undertaken as necessary. In addition, there should be an ADA Coordinator to respond to the reasonable accommodation needs of individuals with disabilities, such as the provision of sign language interpreters.

E. Alternatives to Segregation for People with Serious Mental Health Needs

- Diversion and Release. The County should take concerted action to reduce the size of the jail population and, in particular, the number of people with serious mental illness in custody. Sheriff’s department and jail leadership should partner with patrol, prosecutors, County behavioral health services, the County Board of Supervisors, and other stakeholders to consider alternatives to incarceration, opportunities for release, and diversion mechanisms to reduce the number of people who require mental health treatment in the jails.

- Program-Rich Alternatives. For those who are not diverted or released, the jail should develop program-rich alternatives to segregation for people with serious mental health needs, to ensure they have access to treatment in the most integrated and least restrictive settings.

F. Documentation and Training

- Written Policies. Each of the above principles and topics should be memorialized in a written policy and procedure.

- Notice of Policies. Notice of these policies should be provided at intake and again upon placement into segregation. Inmate handbooks and/or orientation manuals should include summaries of the policy provisions. Anyone placed in segregation should be notified of the relevant provisions and provided full access to the written policy upon request.

- Training. The jail should routinely train custody, health services, and other staff on relevant policy provisions.

- Audits. The jail should conduct CQI reviews and audits as appropriate.

- Data Collection and Publication. The jail should collect and, with appropriate redactions, make publicly available data on its use of segregation.

IV. Conclusion

We thank the County for explaining their system and for considering what we have to say. To ensure the County complies with applicable laws, the County should work collaboratively with us to create meaningful change that will benefit the entire community: the people incarcerated in the jails, the people who work in the jails, and the County as a whole.

We propose a meeting with leadership from custody and CHC in the coming weeks via Zoom or Teams platform to discuss this letter and any progress you have made since our December 14, 2022 visit. We would then hope to meet in person and conduct another visit thereafter.

Please let us know when you are available to meet with us next month. Thank you for your ongoing cooperation and courtesy.

Sincerely,

/s/ Jennifer Stark

Jennifer Stark

DISABILITY RIGHTS CALIFORNIA

1831 K Street

Sacramento, CA 95811-4114

(916) 504-5800

www.disabilityrightsca.org

/s/ Donald Specter

Donald Specter

Tess Borden

A.D. Lewis

Margot Mendelson

PRISON LAW OFFICE

General Delivery

San Quentin, CA 94964

(510) 280-2621

www.prisonlaw.com

Cc: Kimberly D. Johnson, Interim County Counsel Patrick Withrow, Sheriff

- 1. Disability Rights California is the protection and advocacy system for the State of California, with authority to investigate facilities and programs providing services to people with disabilities under the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights (“PADD”) Act, the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness (“PAIMI”) Act, and the Protection and Advocacy for Individual Rights (“PAIR”) Act. The patients and clients we interviewed fall under the federal protections of the PADD Act and/or the PAIMI Act, and their implementing regulations. The PAIMI Act defines probable cause as “reasonable grounds for belief that an individual with mental illness has been, or may be at significant risk of being subject to abuse or neglect.” 42 C.F.R. § 51.2. The PAIMI Act and PADD regulations also contain definitions of abuse and neglect. See 42 C.F.R. § 51.2; 45 C.F.R. § 1326.19.

- 2. Board of State and Community Corrections, Adult Detention Facility Living Area Space Evaluation, Zunino Facility, Honor Farm, 2020-2022, available at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/10Cn7LtRUmt-5jX5PRehH92ONdUkoaH7e.

- 3. Placing a person in segregation for behavior that is a manifestation of their disability punishes people for their disability. Just as it is inappropriate to place a person in segregation as punishment for having a disability, it is inappropriate to place a person in segregation for behaviors that are a manifestation of that disability. As described further below, such practices exacerbate serious mental health needs and can amount to discrimination on the basis of disability. For these reasons, we recommend mental health assessments prior to placement in segregation.

- 4. While people with serious mental health needs should not be housed in segregation, their placement in general population units may not always be appropriate for their clinical needs. As described in Section III.E, San Joaquin should develop program-rich alternatives to segregation to meet the specific needs of this population. Sacramento County has implemented a program-rich alternative to segregation for people with serious mental health needs in its jails, called the High Security Intensive Outpatient (“IOP”) Unit.

- 5. This individual appeared to read large capital letters more easily. On site, we stressed the urgency of providing a sign language interpreter immediately and to work with this individual to identify and utilize their primary and secondary methods of communication.

- 6. As we explained to jail leadership on site, while mental health services should indeed be conducted in private rooms, people may not want others they live with to know they are seeking mental health services. Given the location in-unit, the “mental health interview” language painted on the door should be removed so as not to announce the nature of any clinical encounter that may occur there.

- 7. We recognize that county jails must take into account physical plant limitations and classification considerations in segregation units. We would welcome a conversation with the County about how to maximize out-of-cell time for people in segregation given the structure of the particular facility.