Restraint and Seclusion in California Schools: Findings and Recommendations from the 2021-22 School Year Data

Restraint and Seclusion in California Schools: Findings and Recommendations from the 2021-22 School Year Data

In September 2018, Governor Brown signed AB 2657, a DRC-sponsored bill that created new protections for California students against dangerous forms of restraint and seclusion. AB 2657 also restored restraint and seclusion data collection and reporting requirements beginning with the 2019-2020 school year.

Restraint and Seclusion in California Schools: Findings and Recommendations from the 2021-22 School Year Data

Robert Borrelle, Supervising Attorney, Investigations Unit

Elissa Monteiro-Endow, Data Analyst, Legal Advocacy Unit

Executive Summary

Disability Rights California (DRC) is California’s federally designated Protection and Advocacy agency. For decades we have worked to improve California’s school restraint and seclusion laws and practices through abuse and neglect investigations, public reporting, and legislative advocacy.

In September 2018, Governor Brown signed AB 2657, a DRC-sponsored bill that created new protections for California students against dangerous forms of restraint and seclusion.1 AB 2657 also restored restraint and seclusion data collection and reporting requirements beginning with the 2019-2020 school year.

A year later, DRC issued Protect Children’s Safety and Dignity: Recommendations on Restraint and Seclusion in Schools, a report that called for additional reforms that built upon the promise of AB 2657.2 In the report, DRC argued that recent restraint and seclusion incidents in schools showed that California must enact greater protections for students. Among the report’s recommendations were calls to prohibit prone restraint and impose independent data reporting requirements on nonpublic schools. However, neither the California Department of Education (CDE) nor the Legislature acted.

Five years later, schools have reopened following the COVID-19 closures, and the first full year of AB 2657 restraint and seclusion data is available for the 2021-22 school year. It is time for California to revisit the important topic of restraint and seclusion in schools. In this report, we renew our call for increased protections against prone restraint and other dangerous techniques still permitted under California law and issue findings and recommendations based on our analysis of the newly released data.

Our priority recommendations are:

- California must ban prone, or facedown, restraint in schools. Prone is a proven hazardous and potentially lethal restraint position that is still allowed in California schools. There are many examples in California of injuries and even death from prone restraints in schools, including the tragic death of Davis Joint Unified School District student Max Benson in November 2018. Most states prohibit prone restraint in schools, including New York, which adopted its ban in July 2023. DRC urges California to join these states and end this inherently dangerous practice in its schools.

- If CDE does not clarify the scope of the “peace officer” exception in current restraint reporting requirements, the Legislature must step in to do so. AB 2657 explicitly exempts physical and mechanical restraints by school resource officers and other security personnel made for “detention or for public safety purposes.” More and more California districts are using school police officers to administer routine discipline, so this exception can easily hollow out the current data collection and reporting obligations. DRC calls on the CDE to clarify that this narrow exception is not a blanket carveout for all restraints by police in schools. If it does not, the Legislature must amend the statute to eliminate the exception or at least clarify its scope.

- The CDE must address the significant underreporting of restraint and seclusion in California schools. AB 2657 aimed to improve the accuracy of restraint and seclusion data by setting clear definitions and mandating district reporting on an annual basis. Yet most California school districts, including some of its largest, still reported zero incidents of restraint or seclusion in 2021-22. Given historical data and current reports, this figure is not credible and likely represents gross underreporting. The CDE cannot effectively monitor and enforce state law protections without accurate data. It must do more to enforce reporting requirements and correct district underreporting.

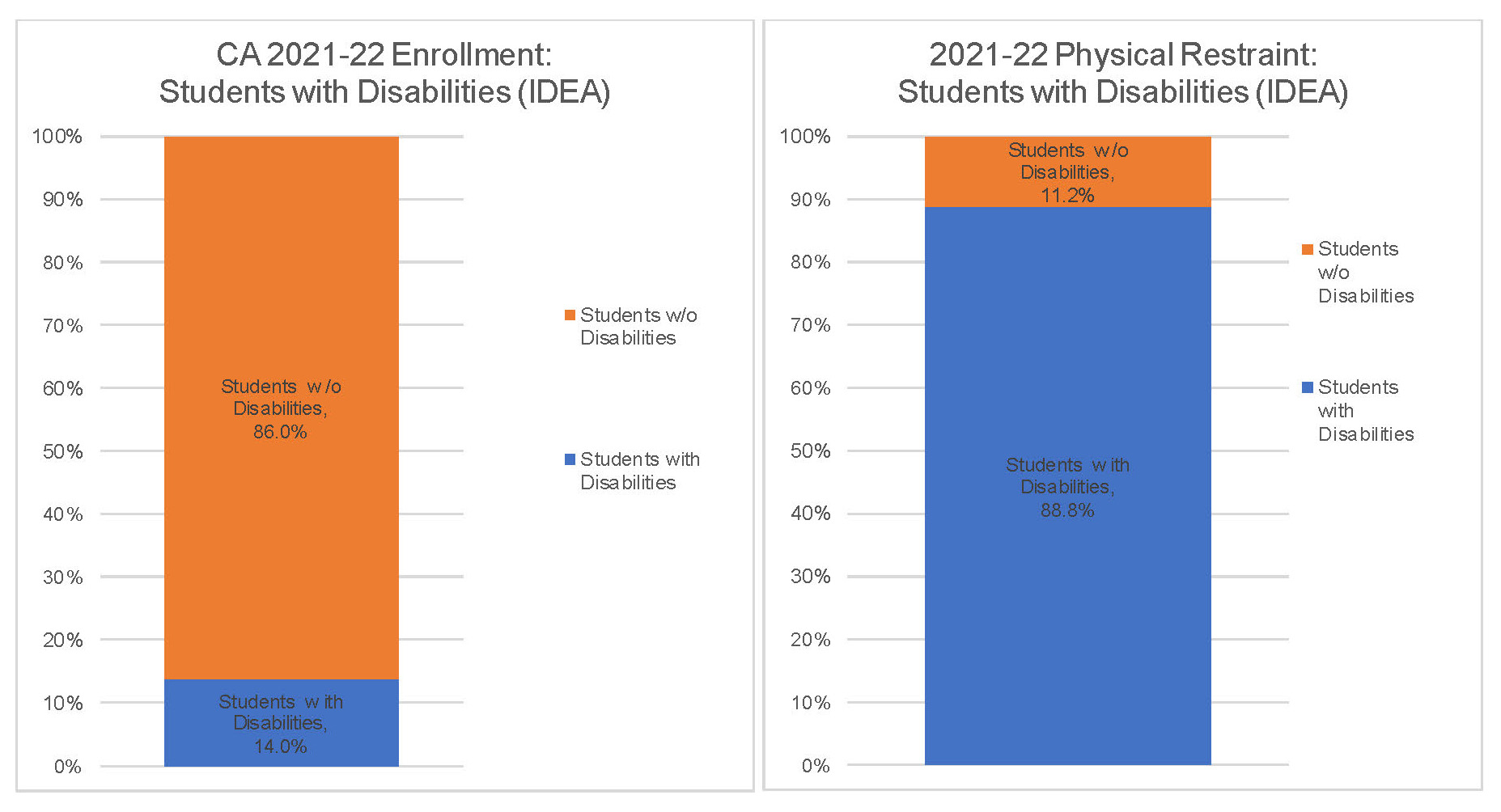

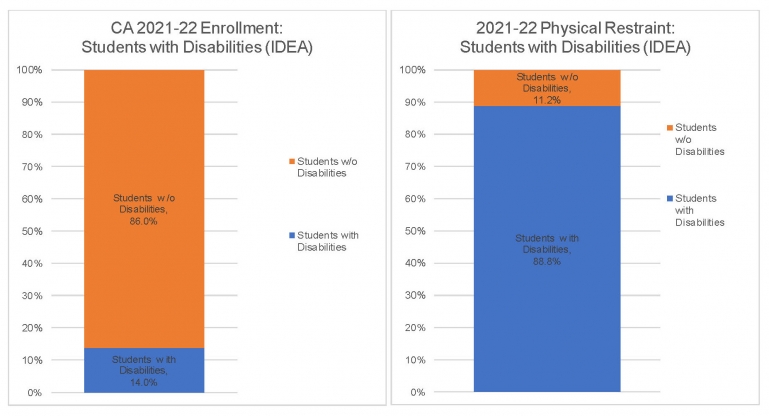

- The CDE and school districts must address the shameful racial disparities that were reported for the 2021-22 school year data. Black students made up 5.1% of the California student population in 2021-22 school year but 17.5% of all students physically restrained, 24.0% of those secluded, and 39.1% mechanically restrained. Students with disabilities, who make up about 14% of students in California, represented 88.8% of students physically restrained and 50% of those secluded. The CDE must address these disparities as part of its monitoring and enforcement responsibilities. Districts and school sites should also increase the accessibility and transparency of their restraint and seclusion data to raise school communities’ awareness of data disparities and help them facilitate solutions.

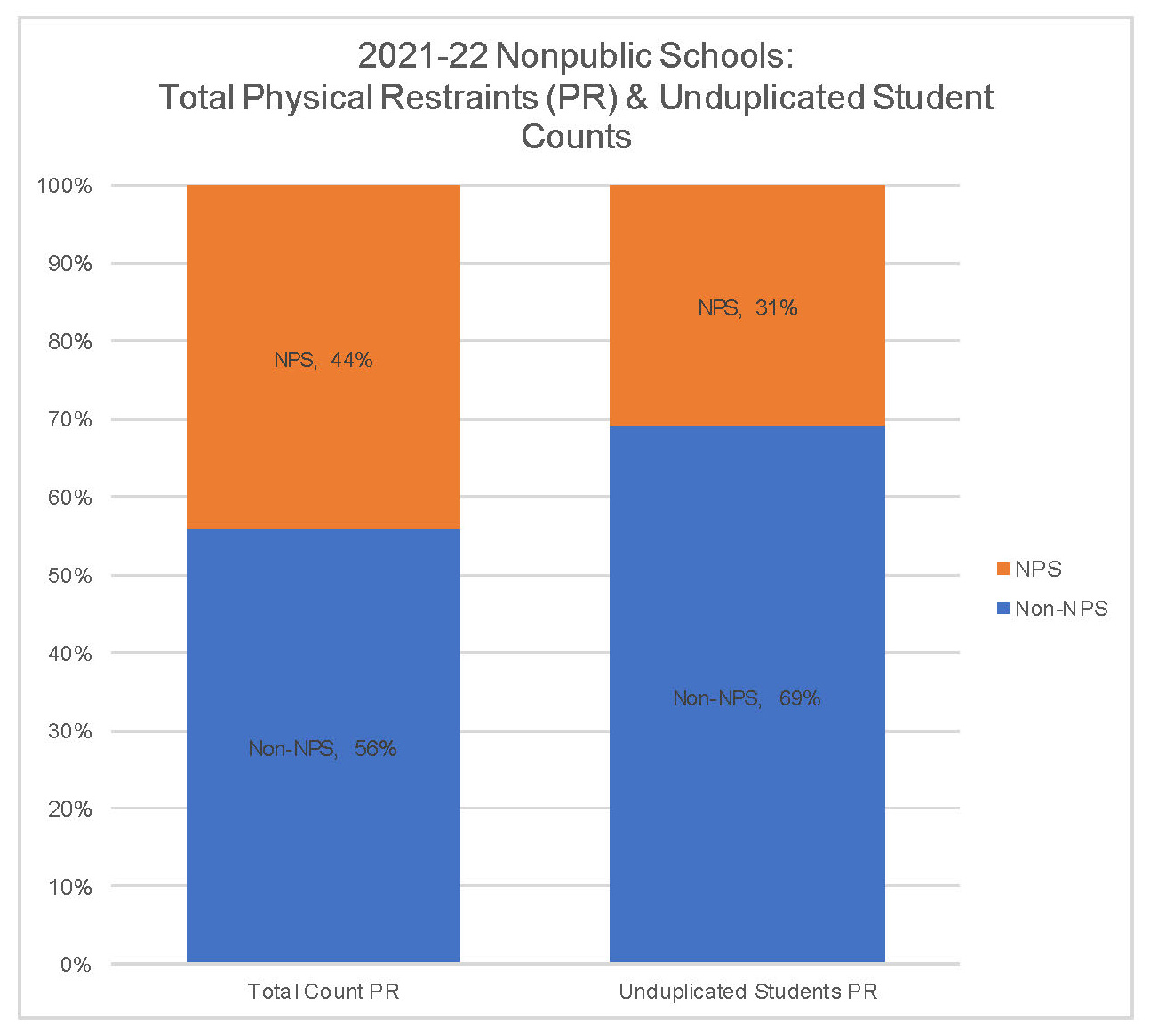

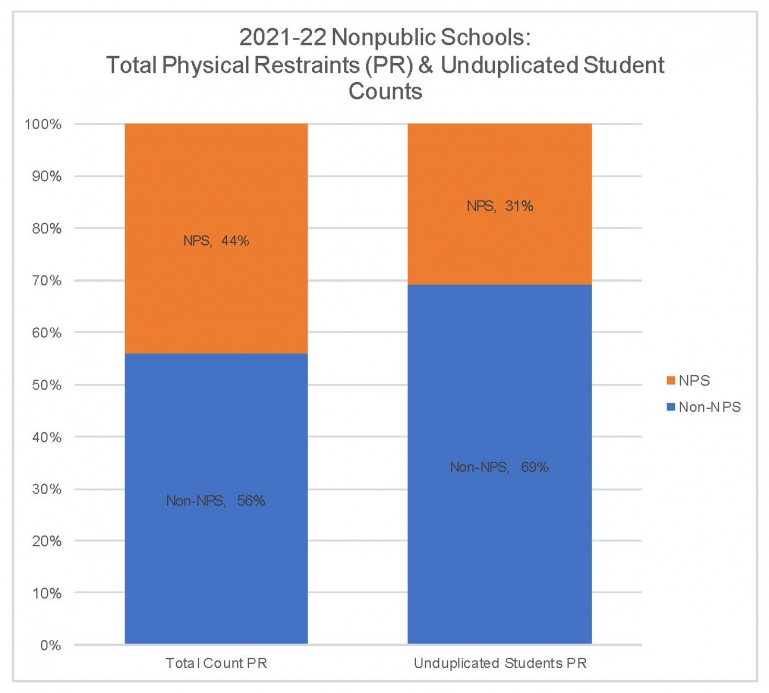

- The Legislature must close the reporting loophole that shrouds restraint and seclusion practices in Nonpublic Schools. Students with disabilities attending nonpublic schools made up a disproportionate number of all California students restrained or secluded in the 2021-22 school year. Yet the AB 2657 reporting framework attributes these incidents to the students’ home school district, not their nonpublic school. This hinders the CDE’s ability to effectively monitor restraint and seclusion practices in individual nonpublic schools. DRC has long called for the Legislature to create an independent reporting requirement for nonpublic schools and renews that call here.

AB 2657: New Protections for California Students

The California Legislature enacted AB 2657 in 2018. A DRC-sponsored bill, AB 2657 filled gaping holes in the existing state law protections against restraint and seclusion in schools.

First, AB 2657 extended protections against excessive restraint and seclusion to all students, with or without disabilities; prior state law protections applied only to students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).3 Among its most powerful protections is an express prohibition on seclusion and restraint of any kind “as a means of coercion, discipline, convenience, or retaliation by staff.”4 Restraint and seclusion techniques are permitted “only to control behavior that poses a clear and present danger of serious physical harm to the pupil or others that cannot be immediately prevented by a response that is less restrictive.”5

Second, AB 2657 defined key terms for the first time. Before AB 2657, state law regulated only the use of undefined “emergency interventions” on students with IEPs.6 In practice, confusion over what constituted an “emergency intervention” resulted in unreliable and inconsistent incident documentation reporting.7 The new definitions align with the ones used for years by the U.S. Department of Education in its Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC):

- “Mechanical restraint” means the use of a device or equipment to restrict a pupil’s freedom of movement.

- “Physical restraint” means a personal restriction that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a pupil to move the pupil’s torso, arms, legs, or head freely.

- “Prone restraint” means the application of a behavioral restraint on a pupil in a facedown position.

- “Seclusion” means the involuntary confinement of a pupil alone in a room or area from which the pupil is physically prevented from leaving.8

Finally, starting with the 2019-2020 school year, AB 2657 required school districts to annually collect and report their restraint and seclusion data to the CDE.9 Districts have not been required to report any restraint and seclusion data to the state since the repeal of the Hughes Bill in 2013.10 Data is critical to state and local oversight activities, including identifying and addressing trends and recognizing successful alternative strategies or programs – all essential components to reducing restraint and seclusion. The CDE posted the 2021-22 school year data on its website in December 2022.11

However, AB 2657 contained several loopholes and omissions that have hindered its effectiveness in the five years since its enactment. This report includes findings to support our five key recommendations to CDE and the Legislature to safeguard California school children and prevent needless death, injury, and trauma.

Findings and Recommendations

This report builds on DRC’s decades of advocacy to improve California’s restraint and seclusion laws and practices. The use of restraint and seclusion in schools can cause profound physical and psychological harm to children. While the need to address trauma is increasingly viewed as an important component of effective educational service delivery, restraint and seclusion are not trauma-informed practices.12 They can be counter-productive to treatment, disrupt essential adult-child relationships, and impede children’s social and emotional learning, especially among vulnerable children with severe trauma histories.13 There continues to be no evidence that using restraint or seclusion is effective in reducing the occurrence of the problem behaviors that frequently precipitate the use of such techniques.14

The following findings are informed by our advocacy implementing AB 2657’s provisions and our review of the 2021-22 school year data released by the CDE in December 2022.

Finding No. 1: California school districts continue to employ the highly dangerous practice of prone, or facedown, restraint, which has been banned in over thirty other states and rejected by the U.S. Department of Education.

Prone restraint is a potentially lethal restraint position for both children and adults.15 Death can occur from positional asphyxia, which is an insufficient intake of oxygen from a body position that interferes with one’s ability to breathe. Even without any other contributing factors, simply restraining a person prone restricts the ability to breathe, thereby lessening the supply of oxygen to meet the body’s demands. Struggle during a prone restraint increases the body’s demand for oxygen and creates an even graver risk of causing respiratory compromise. Pressing a knee or hand into the back of a person in prone position to gain physical control – a tactic police used in the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 – further limits the ability to expand the lungs and breathe.16

Despite its inherent risks, prone restraint is still permitted in California public schools today. The Education Code defines prone restraint as the “application of a behavioral restraint on a pupil in a facedown position.”17 The U.S. Department of Education has long recommended that prone restraints never be used in schools “because they can cause serious injury or death.”18

Unfortunately, AB 2657 did not include a ban on prone restraint. It directed only that if prone restraint is used, “a staff member shall observe the pupil for any signs of physical distress[.]”19 The Education Code still expressly permits the “prone containment” of special education students by “trained personnel.”20

These are not adequate safeguards against the inherent dangers of prone restraint. Even prone restraints by trained staff can cause injuries or even death. For instance, all staff involved in the prone restraint deaths examined in DRC’s 2002 report The Lethal Hazard of Prone Restraint: Positional Asphyxiation were current in their restraint certification.21 Injuries can also occur immediately or suddenly upon the application of prone restraint, negating the effectiveness of direction observation as a safeguard.22

Tragically, there are recent examples in California of injuries and even death from prone restraints in schools:

- On November 28, 2018, a thirteen-year-old Davis Unified School District student with autism died following prolonged prone restraint at Guiding Hands Nonpublic School. Guiding Hands’ staff held the student in prone restraint for over an hour and a half. CDE’s investigation revealed that the student warned his teacher he was going to vomit and pleaded to use the restroom but was forced to urinate on himself. He became unresponsive during the restraint and later died. CDE investigated the school site and revoked Guiding Hand’s license to operate in January 2019.23

- On June 8, 2022, the CDE suspended the certification of Independent Educational Program, Inc., a K-12 nonpublic school in Anderson, Shasta County, after its investigation uncovered “systemic” unlawful restraint practices.24 The CDE’s report describes many incidents of excessive restraint, such as the prone restraint of a student with disabilities for over an hour that resulted in pain and bruising. In another incident, staff held a student with an IEP in a prone restraint with adult staff “switching out” 4-5 times (staff did not document the length of the restraint). The CDE determined that staff disregarded obvious signs of physical distress during other restraints, including one student who vomited and another who urinated on himself.

Given these examples and the extreme danger from prone restraint in any situation, DRC’s position is that only a total and complete ban will ensure the safety of California students.

In recognition of these dangers, on February 14, 2023, Senator Dave Cortese (D-San Jose) introduced Senate Bill (SB) 483. This bill will prohibit the use of prone restraint, defined to include prone containment, by educational providers.25 If SB 483 becomes law, California would join the over thirty other states that ban the use of prone restraints in their schools.26 Illinois, for example, enacted a ban on prone restraint and locked seclusion in August 2021 after a Chicago Tribune-ProPublica investigation revealed abuses.27

Like California, many of the holdout states are currently considering bills that would ban prone restraint in schools. In February 2023 the New York State Legislature introduced the “Keeping All New York Students Safe Act,” a bill would ban chemical, mechanical, prone and supine restraints in New York schools.28 Later in July 2023, the New York Board of Regents unanimously adopted new regulations banning prone restraint and other harmful techniques in schools.29 In June 2023, the Texas Legislature introduced, but failed to pass, a bill that would have banned prone and supine (face-up) restraints schools.30 The bill was in part a response to the death of a 21-year-old student with disabilities from a prone restraint in March of 2021.31

In sum, the time has come for California to end prone restraint in schools. DRC supports the passage of Senate Bill 483 and urges the California Legislature to join the states that have enacted their own ban on prone restraint.

Finding No. 2: The “peace officer or security personnel” restraint exception in AB 2657 has unduly weakened the bill’s protections and undermines oversight.

AB 2657 contained an exception that carved out from its protections mechanical and physical restraints by “peace officers or security personnel” used for “detention or for public safety purposes.”32 The purpose was to differentiate restraints by school resource officers and other campus security personnel from those by “educational providers,” meaning those who “provide educational or related services, support, or other assistance to students.”33

This exception now threatens to eviscerate the protections in state law. Over the past few decades, school districts have increasingly created their own school security forces or contracted with county sheriff and city police departments to place school resource officers and security personnel on campus. As school police presence increased, districts relied on them more to address minor and routine behavioral violations that traditionally teachers or school administrators would have managed. Now, instead of discipline being enforced by educational providers, as the current law contemplates, school police have increasingly assumed that role.

For example:

- DRC released an investigation report on the Antelope Valley Union High School District’s school police practices in May 2023. DRC’s expert Dr. Jaime Hernandez found that teachers were instructed to contact campus security officers rather than administrators when students misbehave in their classrooms. Dr. Hernandez also found that the District’s services agreement with the Los Angeles Sheriff Department did not specify sheriff deputies’ scope of work at all, let alone when they are to intervene in minor student misconduct. In all, DRC’s two-year investigation into the District revealed that school police involvement escalated minor student misconduct into citations, physical and mechanical restraints, and even arrests.34

- DRC is also part of a legal team that brought a lawsuit against the Riverside County Sheriff Department and the Moreno Valley Unified School District on behalf of an 11-year-old Black student with disabilities handcuffed at least four times by school police officers in response to minor or disability-related behaviors.35

- A 2021 report by the ACLU of Northern California found that most California districts give staff complete discretion to call police to address student misbehaviors traditionally handled by school staff such as administrators or counselors. Less than 4% of districts had policies limiting police contact for rule-breaking or minor offenses.36

- The California Department of Justice reached a settlement with the Stockton Unified School District in 2019 after an investigation uncovered discriminatory policies and practices by the District’s police force that led to students being criminalized for minor misconduct.37

A careful reading of the law would not exempt all restraints by school police, but only those used for “detention or for public safety purposes.” However, CDE and school districts have interpreted the “peace officer” exception in current law as a blanket carveout of all restraints by school security personnel. This may partially explain the significant underreporting of restraint and seclusion data discussed in the next section. But it may also permit school security personnel to use otherwise prohibited techniques when addressing minor disciplinary infractions and exempt their restraints from key protections like incident documentation and reporting.

For example, in November 2020, DRC and another advocacy group, Public Counsel, learned of a 16-year-old Black student with disabilities subjected to multiple restraints by school security guards. In one incident, a security guard physically intervened in a verbal argument between the student and his cousin and body slammed him to the ground. In another incident, the student took a break in the hallway as permitted by his behavioral intervention plan and kicked a trash can. A school security guard arrived and after an argument physically restrained the student, handcuffed him, escorted him to a squad car, and brought him to the sheriff’s station.38

Given that there was no dispute about what occurred, these incidents clearly violated the protections in AB 2657 because the physical and mechanical restraints were used in non-emergency situations where there was no threat of physical harm to the student or others. DRC and Public Counsel filed a complaint with the CDE, alleging the school security guards violated state law, including a failure to document the incident and using restraint in a non-emergency situation. The CDE, however, held that the state law requirements did not apply to the security guards’ actions because (1) they were not educational providers; and (2) their use of force was for public safety purposes.39

This result is contrary to both the spirit and letter of AB 2657 and ignores the reality that school security personnel administer routine discipline in schools across the state. DRC urges the CDE to clarify that this narrow exception is not a blanket carveout for all restraints by police in schools. If it does not, the Legislature must eliminate the exception, or at the very least clarify that it is not a blanket carveout of all physical and mechanical restraint by school security personnel.

Finding No. 3: Current restraint and seclusion data is unreliable because of widespread underreporting.

The CDE released the restraint and seclusion data for the 2021-22 school year on December 15, 2022.40 This was the first full year of data the CDE released since the passage of AB 2657. The CDE previously released restraint and seclusion data for the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years, respectively, but the COVID-19 school closures truncated the datasets.41 The 2021-22 collection presents the first opportunity for the public to analyze AB 2657 restraint and seclusion data across an entire school year.

Statewide Restraint and Seclusion Counts (2021-22 SY)

| Data Category | Count |

|---|---|

| Count of Physical Restraints | 6,026 |

| Unduplicated Count of Students Physically Restrained | 1,888 |

| Count of Seclusions | 529 |

| Unduplicated Count of Students Secluded | 287 |

| Count of Mechanical Restraints | 97 |

| Unduplicated Count of Students Mechanically Restrained | 64 |

DRC carefully reviewed and analyzed the 2021-22 school year restraint and seclusion data for this report. A particular concern of ours was whether school districts are accurately reporting data to the CDE. Underreporting has long been a problem with the U.S. Department of Education’s biannual Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC). Some of the largest California school districts have not reported a single incident of restraint or seclusion of any student in their CRDC data.42

Upon review, the 2021-22 collection likely represents a significant underreporting of restraint and seclusion in California schools. School districts reported 6,026 incidents of physical restraint and 529 seclusions in 2021-22. By comparison, in 2011-2012 school year, the last year of the Hughes Bill data collection, California schools collected 22,043 behavioral emergency reports just for students with IEPs.43 The dramatic drop over a ten-year period cannot be attributed to an improvement in district practices, especially where AB 2657, for the first time, defined key terms and extended protections to nondisabled students.

In all, 74.0% (735 of 993) of all reporting school districts reported zero restraint or seclusions in 2021-22. The district-level breakdowns again reveal the scope of the likely underreporting:

- Long Beach Unified School District, the fourth largest district in the state with over 65,000 students,44 reported zero restraints or seclusions.

- San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD), the sixth largest district at over 55,000 students, has reported zero restraints or seclusions in all three AB 2657 collections. By comparison, in 2011-12, SFUSD logged 1,253 behavioral emergency reports documenting “emergency interventions” used on students with IEPs.45

- Garden Grove Unified School District, the eighteenth largest district with over 38,000 students, similarly reported zero restraints or seclusions.

It is possible that declining enrollment and students electing Independent Study for the 2021-22 school year46 had a small impact on the data. But neither independent study nor COVID-19 can explain such distorted figures. Districts reported restraining and secluding fewer students in the 2021-22 school year than in 2019-20, even though the 2019-20 data was impacted by school closures when all students moved to distance learning in March 2020.

Unduplicated Physical Restraint and Seclusion Counts, 2019 to 202247

| School Year | Unduplicated Count of Students Physically Restrained | Unduplicated Count of Students Secluded |

|---|---|---|

| 2019-2020 | 2,457 | 361 |

| 2020-2021 | 620 | 79 |

| 2021-2022 | 1,888 | 287 |

As noted above, the extreme drop in reported incidents may also be attributed to the “peace officer or security personnel” exception. For example, California school districts reported that just 64 students were mechanically restrained in 2021-2022. As more educational providers defer to school police regarding student behavior, even for students with IEPs and behavior intervention plans, more physical and mechanical restraint incidents will go unreported.

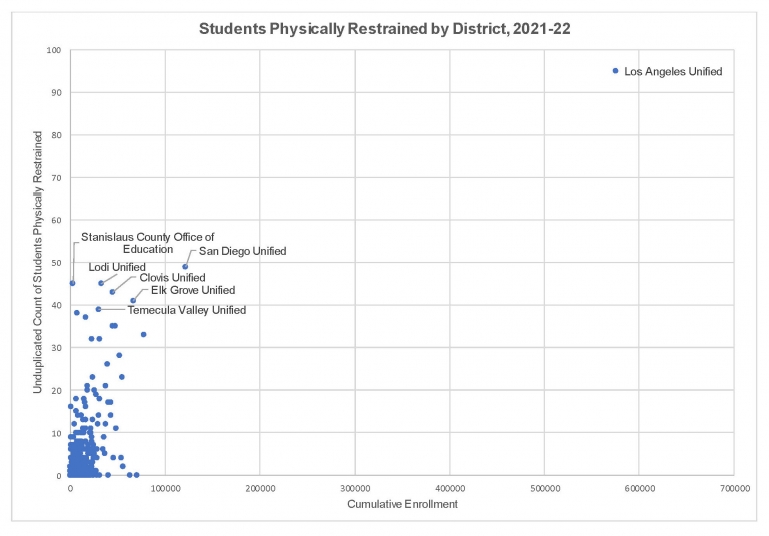

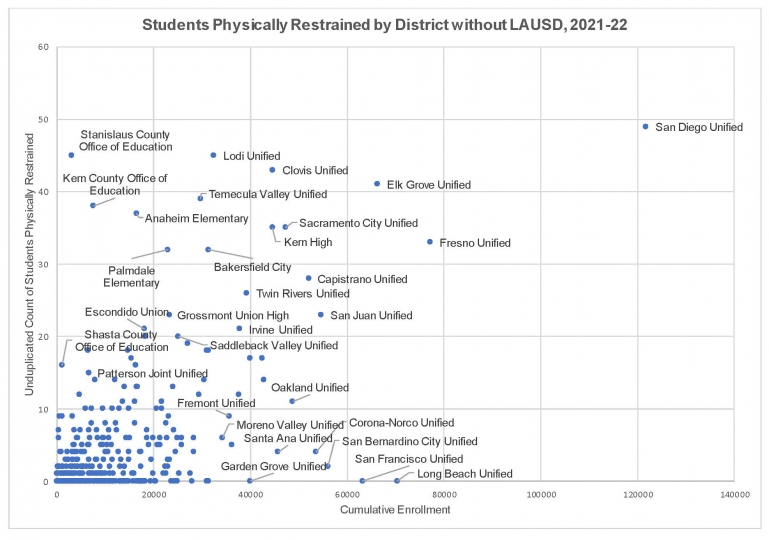

Finally, there was improved reporting from some larger school districts in the 2021-22 collection. The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), for example, received media scrutiny in the past for reporting zero incidents of restraint or seclusion to the CRDC despite being the second largest school district in the country.48 But in 2021-22, LAUSD reported restraint and seclusion data to the CDE (see chart below). The Elk Grove Unified School District, the fifth largest with over 62,000 students, is another example of a large school district reporting data to the CDE in 2021-22 after reporting zero incidents to the CRDC in the past. While data accuracy statewide still deserves scrutiny, large districts reporting any restraints or seclusions to oversight agencies is an important step forward.

DRC urges the CDE to enforce AB 2657’s reporting requirements and identify underreporting as part of its monitoring and enforcement framework. Continued underreporting will only undermine public confidence in the data and fail to provide decision makers with the reliable information they need to make informed policy decisions to protect students.

DRC also urges the CDE to seek out technical assistance from the U.S. Department of Education, which is improving its own federal CRDC collection. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded in an April 2020 analysis that the CRDC data was inaccurate and that the U.S. Department of Education’s quality control processes are “largely ineffective or do not exist.” It recommended that the federal education agency, among steps, “identify the factors that cause underreporting and misreporting of restraint and seclusion and take steps to help school districts overcome these issues.”49 AB 2657 has the same data collection and reporting requirements as the CRDC (albeit on an annual basis),50 so it likely suffers from these same data quality control problems.

Finding No. 4: California must address the shameful disparities in its rates of restraint and seclusion.

One of the Legislature’s aims with AB 2657 was to address the persistent, disproportionate restraint and seclusion of students with disabilities and students of color.51 According to the most recent federal data available at the time, students with disabilities made up 13% of the student population nationally but 80% of all students subjected to a physical restraint and 77% subjected to seclusion.52 The disparities are even worse for students of color with disabilities. Black students with disabilities represent 18% of all students with IEPs nationally but 26% of all students with IEPs subjected to a physical restraint and 34% of those subjected to mechanical restraints.53

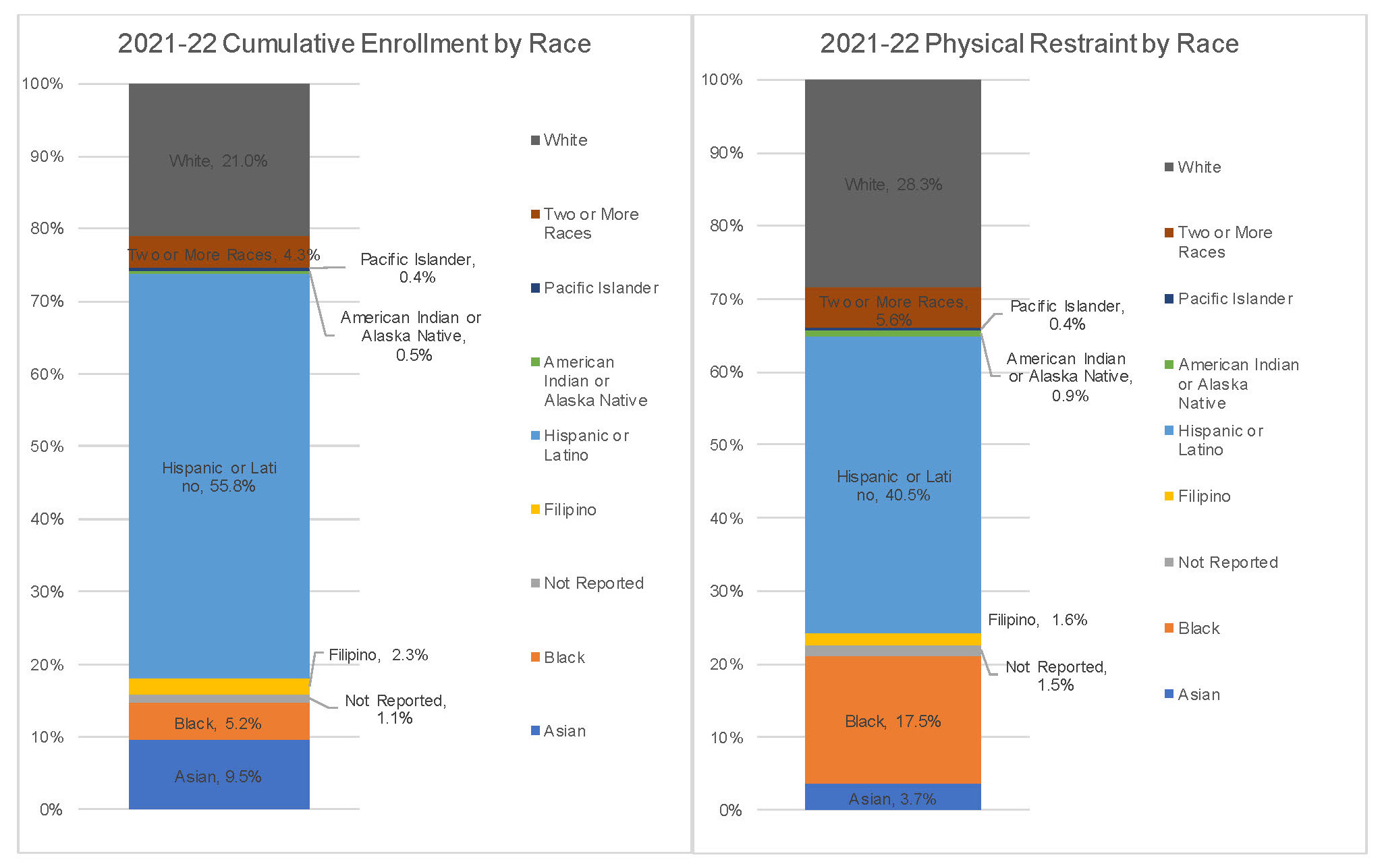

DRC’s analysis of the 2021-22 data that California school districts did report, however, revealed continued, shameful disparities by race/ethnicity and disability status:

- Black students made up 5.2% of the student population in 2021-22 school year but 17.5% of all students physically restrained, 24.0% of those secluded, and 39.1% of all students mechanically restrained.

- Students with disabilities, who make up about 14% of all students in California, represented 88.7% of all students physically restrained and 49.8% of those secluded.

The U.S. Department of Education recommends that states, districts, and schools examine data disparities (e.g., gender, race, national origin, disability status and type of disability, limited English proficiency, etc.) when reviewing existing policies and procedures on the use of restraint and seclusion.54 Such reviews should be used to determine whether policies are being properly followed, whether procedures are being implemented as intended, and whether school staff should receive additional training on the proper use of restraint and seclusion or positive behavioral interventions and supports.

On February 17, 2023, Assemblymember Dr. Akilah Weber (D-San Diego) introduced AB 1466, a bill that requires California school districts to post the annual restraint and seclusion data that they collect and submit to the CDE on their websites.55 The purpose of the bill is to promote greater data accessibility and transparency for students and families. DRC supports the passage of AB 1466 and believes that improved access to district-level restraint and seclusion data will raise school communities’ awareness of data disparities and facilitate the type of examinations recommended by the U.S. Department of Education.

Finding No. 5: Unless it is closed, the existing NPS reporting loophole will prevent effective oversight by the CDE.

Prior to AB 2657, anecdotal evidence suggested that a disproportionate amount of restraint and seclusion in California schools occurred in nonpublic school, or NPS, settings.56 DRC’s analysis of the 2021-22 school year data confirms that this is indeed the case – nonpublic schools accounted for 44.1% of all reported physical restraint incidents in California in the 2021-22 school year. This is staggering considering only 8,626 of California’s nearly 6 million students (0.2%) attended nonpublic schools this past school year.57

Although AB 2657 tracks aggregate nonpublic school restraint and seclusion data, it does not have data collection and reporting requirements for individual nonpublic schools. Incidents of restraint and seclusion that occur at nonpublic schools are attributed only to the student’s home district. In other words, while we know restraint and seclusion disproportionately occurs at nonpublic schools, we do not know the specific nonpublic schools where this happens.

The Legislature must close this loophole and create an independent reporting requirement for nonpublic schools. Without an independent reporting requirement, the CDE cannot effectively monitor and identify specific nonpublic schools that use excessive or discriminatory restraint and seclusion practices.

Appendix: Notes on Discrepancies in the 2021-22 School Year Dataset

DRC conferred with the CDE regarding two discrepancies we identified in the 2021-22 school year physical restraint dataset:58

1. The incident count of physical restraints at nonpublic schools (NPS=Y) and at other types of schools (NPS=N) added up to more than the total reported incident count (NPS=ALL).

| Academic Year | Aggregate Level | NPS | Reporting Category | Count of Physical Restraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021-22 | State | ALL | Total | 6,026 |

| 2021-22 | State | N | Total | 3,376 |

| 2021-22 | State | Y | Total | 2,656 |

According to the CDE, one school district improperly reported the same restraint incident under the School code and then again under the School NPS code. The CDE’s CALPADS Office is reviewing this submission and considering implementation of more stringent warnings into the data collection system.

2. Similarly, the unduplicated Student count of physical restraints at nonpublic schools (NPS=Y) and at other types of schools (NPS=N) added up to more than the total reported unduplicated Student count (NPS=ALL).

| Academic Year | Aggregate Level | NPS | Reporting Category | Unduplicated Count of Students Physically Restraineds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021-22 | State | ALL | Total | 6,026 |

| 2021-22 | State | N | Total | 3,376 |

| 2021-22 | State | Y | Total | 2,656 |

The CDE explained that during the school year, a student may attend and be physically restrained at one or more schools, including at an NPS and at a non-NPS school. In these instances, the student will be counted once as NPS=Y and once as NPS=N, but only one time under NPS=ALL.

- 1. Statutes of 2018, Chapter 998, codified at Cal. Educ. Code §§ 49005–49006.4.

- 2. See DRC, Protect Children’s Safety and Dignity: Recommendations on Restraint and Seclusion in Schools at 11 (Aug. 13, 2019), https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/post/protect-childrens-safety-and-dignity-recommendations-on-restraint-and-seclusion-in-schools (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 3. See Cal. Educ. Code §§ 56520-56525.

- 4. Cal. Educ. Code § 49005.2.

- 5. Cal. Educ. Code § 49005.4.

- 6. See Cal. Educ. Code § 56521.1.

- 7. DRC, Restraint and Seclusion in Schools: Recommendations for California (June 2015), https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/system/files/file-attachments/CM6101.pdf (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 8. Cal. Educ. Code § 49005.2.

- 9. Cal. Educ. Code § 49006(d).

- 10. The enactment of Assembly Bill No. 86 (Jul. 1, 2013) repealed the Hughes Bill data collection requirements located in Cal. Code Regs., tit. 5, § 3052(i)(9).

- 11. CDE, Restraint and Seclusion Data (Dec. 15, 2022), https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/filesrsd.asp (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 12. Jonathan Bystrynski et al., Predictors of injury to youth associated with physical restraint in residential mental health treatment centers (June 2021). Child & Youth Care Forum (Vol. 50, pp. 511-526). Springer US. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09585-y (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 13. Michael A. Nunno et al., A 26-year study of restraint fatalities among children and adolescents in the United States: A failure of organizational structures and processes. (2022, June). Child & Youth Care Forum (Vol. 51, No. 3, pp. 661-680). Springer US. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10566-021-09646-w (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 14. U.S. Dep’t of Educ., Restraint and Seclusion: Resource Document at iii (May 15, 2012), https://ed.gov/policy/seclusion/restraints-and-seclusion-resources.pdf (last accessed Aug. 4 2023).

- 15. See, generally, DRC, The Lethal Hazard Of Prone Restraint: Positional Asphyxiation (Apr. 2002), https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/system/files/file-attachments/701801.pdf (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 16. Id. at 16-17; Shaila Dewan, Subduing Suspects Face Down Isn’t Fatal, Research Has Said. Now the Research Is on Trial. New York Times, Nov. 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/02/us/police-restraints-research-george-floyd.html (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 17. Cal Educ. Code § 49005.1(g).

- 18. U.S. Dept. of Educ., Restraint and Seclusion: Resource Document, supra n.14, at 16-17.

- 19. Cal Educ. Code § 49005.8(d).

- 20. Cal. Educ. Code § 56521.1(d)(2).

- 21. DRC, The Lethal Hazard of Prone Restraint, supra n.15, at 22-23.

- 22. Id. at 22.

- 23. Respondent’s Opposition to Order to Show Cause re: Preliminary Injunction, at 2, Guiding Hands School, Inc. v. Thurmond (2019) (No. 34-2019-80003050).

- 24. CDE, Nonpublic School Complaint Investigation Report Amended, NPS:1214-21/22 (Jun. 8, 2022). A copy of the report is on file with DRC.

- 25. Sen. Bill 483, 2023-24 Reg. Session (Feb. 14, 2023); see also Press Release, Bill Would Ban The Use Of A Dangerous Restraint Technique Against Students (Feb. 14, 2023), https://sd15.senate.ca.gov/news/bill-would-ban-use-dangerous-restraint-technique-against-students (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 26. Emilie Munson, The U.S. regulates how hospitals can use restraint and seclusion. Why not schools?, CT Insider, Oct. 27, 2022, https://www.ctinsider.com/news/article/school-restraint-seclusion-regulations-legislation-17474953.php (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 27. Jennifer Smith Richards and Jodi S. Cogen, Illinois Dramatically Limits Use of Seclusion and Face-Down Restraints in Schools, ProPublica and Chicago Tribune, May 30, 2021, https://www.propublica.org/article/illinois-dramatically-limits-use-of-seclusion-and-face-down-restraints-in-schools (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 28. Emilie Munson, Bill would restrict restraint and ban seclusion in New York schools, Times Union, Feb. 6, 2023, https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/bill-restrict-restraint-ban-seclusion-new-york-17762385.php (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 29. Emilie Munson, New York approves new rules limiting restraint, seclusion in schools, Times Union, Jul. 17, 2023, https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/new-york-passes-new-rules-restraint-seclusion-18200655.php (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 30. Dominic Anthony Walsh, ‘No accountability’: Kids in special education are routinely restrained. Texas lawmakers could change that, Houston Public Media, Feb. 16, 2023, https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/education/2023/02/16/443879/no-accountability-kids-in-special-education-are-routinely-restrained-texas-lawmakers-could-change-that/ (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023); Silas Allen, Texas parents called for an end to dangerous restraints in schools. It didn’t happen, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Jun. 17, 2023, https://www.star-telegram.com/article276479616.html (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 31. Silas Allen, Fort Worth teachers used illegal restraint before student’s death, police report shows, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Nov. 10, 2022, https://www.star-telegram.com/news/local/education/article268519762.html (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 32. Cal. Educ. Code § 49005.1(d)(2)(A) and (f)(2).

- 33. Cal. Educ. Code § 49005.1(b).

- 34. DRC, Investigation into Various Compliance Complaints Against the Antelope Valley Union High School District at Sec. 6, pp. 295-363 (May 24, 2023), https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/latest-news/investigation-into-various-compliance-complaints-against-the-antelope-valley-union-high (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 35. Press Release, Court Denies Motion to Dismiss Legal Case Against Moreno Valley Unified School District (MVUSD) (Aug. 4, 2021), https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/press-release/court-denies-motion-to-dismiss-legal-case-against-moreno-valley-unified-school (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 36. ACLU NorCal, The Right to Remain a Student: How CA School Policies Fail to Protect and Serve (Sept. 22, 2021), https://www.aclunc.org/publications/right-remain-student-how-ca-school-policies-fail-protect-and-serve (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 37. Press Release, California Department of Justice, Stockton Unified School District Enter into Agreement to Address Discriminatory Treatment of Minority Students and Students with Disabilities (Jan. 22, 2019), https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/california-department-justice-stockton-unified-school-district-enter-agreement (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 38. CDE, Complaint Investigation Report, Case No. S-0338-20/21 (Feb. 1, 2021). A copy of the report is on file with DRC.

- 39. Id. at p. 7.

- 40. CDE, Restraint and Seclusion Data, supra n. 11.

- 41. Id.

- 42. See, e.g., DRC, Restraint and Seclusion in Schools: Recommendations for California, supra n. 7 at 18.

- 43. Id. at 17. A “behavioral emergency report,” or BER, is a form school staff must complete after the use on an emergency intervention on a student with an IEP. See Cal. Educ. Code § 56521.1(e).

- 44. CDE, Largest & Smallest Public School Districts 2022-23 (Nov. 1, 2022), https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/ceflargesmalldist.asp (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 45. Jane Adams, Little oversight of restraint practices in special education, EdSource, Apr. 19, 2015, https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/fellowships/projects/little-oversight-restraint-practices-special-education (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 46. For the 2021-22 school year only, AB 130 allowed California students to go on Independent Study if their health would be put at risk by in-person instruction, as determined by their parents. Cal. Educ. Code § 51745(a)(5).

- 47. CDE, Restraint and Seclusion Data, supra n. 11.

- 48. Annie Waldman, “Los Angeles and New York Pin Down School Kids and Then Say It Never Happened,” ProPublica, Dec. 2, 2014, https://www.propublica.org/article/los-angeles-and-new-york-pin-down-school-kids-and-then-say-it-never-happene (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 49. U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-20-345, K-12 Education: Education Needs to Address Significant Quality Issues with Its Restraint and Seclusion Data (Apr. 21, 2020), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-345 (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 50. See Cal. Educ. Code § 49006.2 (“[T]he data collection and reporting requirements contained in this article shall be conducted in compliance with the requirements of the Civil Rights Data Collection”).

- 51. Cal. Educ. Code § 49005(f).

- 52. U.S. Dep’t of Educ., 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection: The Use of Restraint and Seclusion on Children with Disabilities in K-12 Schools at 6-7 (Oct. 2020), https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/restraint-and-seclusion.pdf (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 53. Id. at 10-11.

- 54. U.S. Dep’t of Educ., Restraint and Seclusion: Resource Document, supra n. 14 at 22-23.

- 55. Assem. Bill No. 1466 (2023-2024 Reg. Sess.), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202320240AB1466 (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 56. See, e.g., Hayward Unified Sch. Dist., 117 LRP 41780 (OCR 2017) (OCR determined that in the 2013-14 school year, 94% of restraint and 95% of seclusion in the district occurred in nonpublic schools).

- 57. See CDE, Fingertip Facts on Education in California (Mar. 15, 2023), https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/ceffingertipfacts.asp (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).

- 58. CDE, CALPADS Disciplinary Restraint & Seclusion Data (2021-22) (Sept. 21, 2022), available at: https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/documents/rsddata2122.xlsx (last accessed Aug. 4, 2023).