San Diego County prisoners died after being denied medication, treatment

The end for George Gallegos came on April 21, 2018, when the 55-year-old inmate succumbed to acute pneumonia and severe dehydration while locked up in the San Diego Central Jail.

Three months earlier, Gallegos had been a patient at Metropolitan State Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Los Angeles.

After transferring to San Diego, he lost more than 50 pounds — nearly a fourth of his body weight, his autopsy report said.

Much of the report was blacked out. The readable part said, “the decedent was not under medical care or on a medication regimen.”

A sheriff’s deputy checked on Gallegos only because his pants were slightly pulled down, revealing feces-soiled underwear. The deputy found Gallegos “pulseless and cold to the touch,” the report said.

Gallegos’ bunk and parts of his cell were covered in feces. His cellmate was found kneeling on the floor nearby.

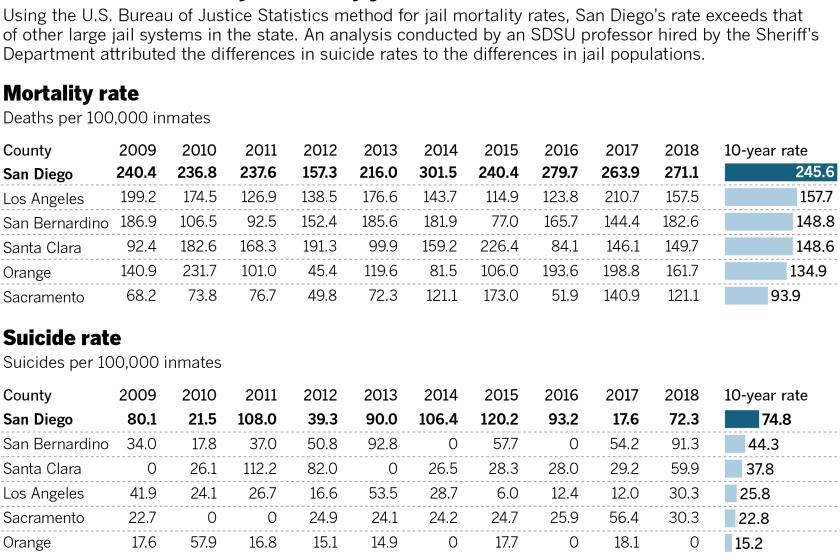

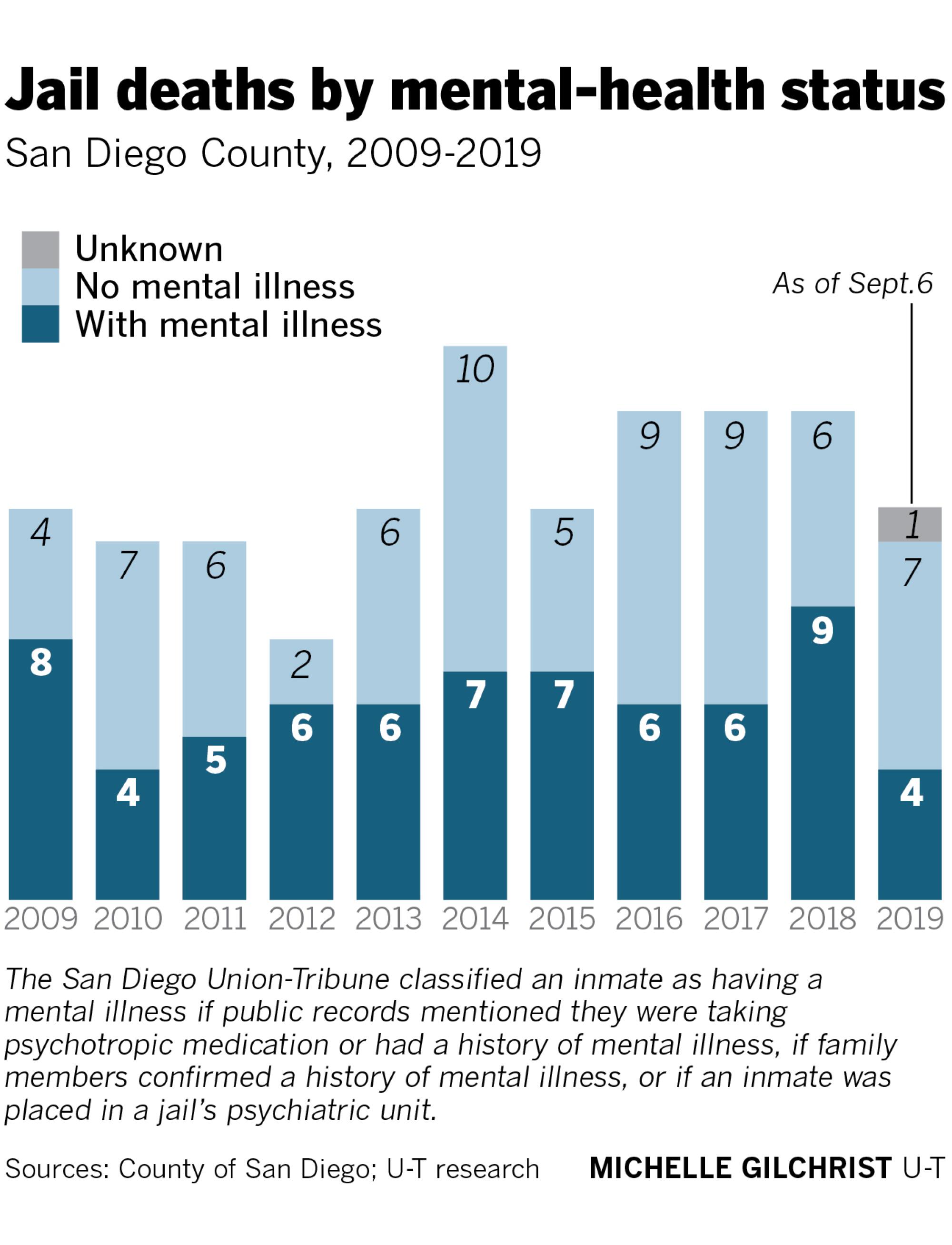

While mentally ill people make up about one-third of the San Diego County jail population at any given time, they represent about half of the 140 in-custody deaths that have occurred since 2009.

A six-month San Diego Union-Tribune investigation found that mentally ill inmates in San Diego County commit suicide at higher rates and are more likely to be killed and more likely to die from treatable medical conditions than inmates in other large California counties.

According to court documents and independent experts, many of the deaths could have been prevented with better monitoring and more effective medical and mental-health care. Advocates say jails are no place for someone suffering from a mental illness.

“We are doing a terrible job for the most severely ill,” said John Snook of the Treatment Advocacy Center, a mental-health nonprofit group based in Arlington, Va.

He said deficiencies in San Diego County jails are not unique. Jails across the nation struggle to appropriately house mentally ill inmates.

“Mental illness is a very specialized area. And if you if you haven’t been trained in that area and you’re not sensitive to it, that’s when problems occur.”

— Alex Landon, San Diego attorney

“It’s just been over and over again, in cities all across the country: people starving to death or dying by dehydration sitting in a jail cell,” Snook said. “They’re not criminals; they’re just off their meds. It is unacceptable that San Diego has not figured that out.”

The Sheriff’s Department said it provides efficient, high-quality care to inmates at a reasonable cost. Last year it spent more than $83 million on inmate health care.

Officials say they are adding training for jail staff and improving intake practices. They also are trying to win accreditation by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, which recognizes the highest-performing jails and prisons.

“Suicide prevention is very important to us,” Cmdr. Erika Frierson, who oversees detentions for the Sheriff’s Department, said in an interview. “If we lose one person, that’s one too many. The sheriff has made this a priority.”

‘A serious problem of quality’

The department’s efforts did not save Ruben Nunez, a 46-year-old San Diego man who was transferred from a state psychiatric hospital to the San Diego Central Jail in August 2015 and died several days later.

Nunez was sent to Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino in 2014 after being found incompetent to stand trial on an assault charge. He had thrown a rock at a passing car after failing to take his medication, according to a lawsuit filed by Nunez’s parents.

When Nunez returned to San Diego County for a competency hearing, he arrived at the jail with paperwork detailing his diagnosis, his health issues and a treatment plan for the course of his jail stay.

Five times the plan mentions that Nunez had a rare condition that caused him to drink water uncontrollably.

At Patton, Nunez was treated for schizophrenia and developed psychogenic polydipsia, which drives a pervasive addiction to water. Medical records included in a lawsuit filed by Nunez’s family show Patton staff monitored him closely, checking his weight, sodium levels and limiting his access to water.

His discharge paperwork spelled out the level of care that Nunez required. Two jail psychiatrists who reviewed Nunez’s file failed to alert anyone about his condition, the plaintiffs alleged.

And a nurse at the jail who performed Nunez’s medical screening appeared not to have read his Patton file. During intake she told Nunez to “Drink plenty of water,” according to the lawsuit.

Nunez was placed in a two-man cell on the jail’s sixth floor. Surveillance footage from the day before he died shows him going back and forth to a water fountain, filling and refilling a cup.

Sometime around 2 a.m. on Aug. 3, a nurse saw Nunez vomiting in his cell and asked a deputy to take him to the jail’s medical unit. An hour later, the same nurse noticed Nunez was still in his cell, the lawsuit says.

By the time a deputy arrived at 3:17 a.m., Nunez was unconscious. When the medical staff arrived 10 minutes later, he didn’t have a pulse and could not be revived, according to his autopsy report.

An investigator from the Medical Examiner’s Office who had been summoned to the jail noted in his report that the cell “smelled of urine and vomit.” There was vomit in the sink, on a table, on the floor, on Nunez’s bunk and bloody vomit splattered on a wall.

After Nunez’s death, the jail’s medical director, Dr. Alfred Joshua, sent an email to top jail staff regarding Correctional Physicians Medical Group, the San Diego company hired to provide mental health treatment at the jail.

“CPMG has put the Sheriff’s Department at risk with the lack of clinical quality assurance and training,” Joshua wrote in the email that was also directed at CPMG head Steven Mannis. “This is not a blame issue but a serious problem with the quality of CPMG providers due to a lack of clinical oversight.”

Joshua resigned from his position last year. He did not respond to interview requests.

Last year, the county Board of Supervisors agreed to pay $1 million to Nunez’s family to settle their wrongful-death lawsuit. Correctional Physicians Medical Group’s contract with the county was terminated in 2017, and it recently settled with Nunez’s family for an undisclosed sum.

Nunez was one of at least 68 mentally ill inmates who died in San Diego County jails over the last decade, according to an analysis by the Union-Tribune of hundreds of autopsy reports, court documents and other public records.

Case after case raises questions about whether the jail’s mentally ill population is being properly cared for and, advocates say, whether some inmates should have been locked up at all.

‘Don’t worry Mom’

Families confronting mental illness often have limited options. Private treatment can be costly, public services can be difficult to secure and prescription drugs can be expensive.

When medication does work, some patients stop taking it, believing they are cured. Often the chemical imbalance recurs and patients engage in behavior that prompts calls to police.

Not long after Heron and Michelle Moriarty celebrated their 18th anniversary, Heron suffered a psychotic breakdown. The East County electrical contractor had been released from the hospital with a handful of prescriptions, but he stopped taking the medication.

In May 2016, Heron ended up at the Vista Detention Facility after throwing a table through a sliding-glass door at his brother’s home in Jamul. Over the next several days, Michelle Moriarty called the jail more than 30 times, she said in an interview, warning them that her husband was suicidal and off his medication.

“I would sit on the phone for half an hour,” she told the Union-Tribune. “But they’re like, ‘Don’t worry, we’re taking care of him.’ They said he’s in good hands.”

Heron Moriarty wrapped a T-shirt around his neck and stuffed another shirt inside his mouth and suffocated. He was found unresponsive in his cell just before 10 p.m. on May 31, 2016.

“I was calling them, telling them I was so scared. I’m worried for his life. I told them over and over and over, anytime I thought of anything. I felt kind of almost dumb calling. I’d hang up and then I’d remember something and call right back.”

— Michelle Moriarty

Moriarty was never placed on suicide watch or treated for his illness, according to a lawsuit filed by the widow against the county.

Weeks before his illness struck, Heron Moriarty had been a mentally fit business owner and devout family man, his family said. Now his widow is raising three children by herself and has filed a wrongful-death lawsuit.

“I was thinking he was going to get the help he needed,” Michelle Moriarty said.

In court filings, county lawyers have said Moriarty’s death was not the jail staff’s fault, adding that they “are not liable for failing to diagnose mental illness or addiction.”

Rochelle Nishimoto has a similar story. Her son, Jason, successfully managed his schizophrenia for more than 20 years, working as a welder on Navy ships along San Diego Bay.

But in 2015, Jason began experiencing side effects from medication. He survived multiple suicide attempts but landed at the Vista Detention Facility after an altercation with his brother, who called 911 to report the emergency.

Rochelle Nishimoto spoke to a nurse at the Vista jail to detail her son’s condition.

“OK, don’t worry, Mom, we’ll take good care of your son,” she said she was told.

The 44-year-old welder with no previous criminal record was supposed to be under special observation and was not supposed to have access to a bed sheet, the family’s lawsuit said.

Nevertheless, Jason Nishimoto was able to hang himself with the sheet.

In February, San Diego County agreed to pay Rochelle Nishimoto $595,000 to settle the lawsuit.

Some in-custody deaths are less clear-cut. They don’t generate lawsuits or provoke outrage from surviving family members, although they do prompt oversight scrutiny.

Bruce Stucki, for example, was homeless and a chronic alcoholic when he was booked into the Vista Detention Facility in 2017. He had been arrested for public intoxication after wandering into traffic.

He was 53 the day he died from complications related to alcoholism.

A report from the county Citizens’ Law Enforcement Review Board, a volunteer panel that reviews jail deaths and complaints against sheriff’s deputies, found medical staff failed to place Stucki on the jail’s alcohol-withdrawal protocol even though they knew he was at risk for delirium tremens, a serious complication that can lead to death.

“During Mr. Stucki’s medical screening, it was determined that he was a chronic consumer of vodka and would ‘shake’ when he stopped consuming it,” the review board said.

Stucki was “found hallucinating in his cell” two days after he was booked. He was given a dose of the medication Librium to ease his withdrawal symptoms and placed into a single cell where, several hours later, deputies found him slumped over.

In its summary, the review board issued findings of “not sustained,” meaning there was not enough proof to conclude that jailers had failed to follow department rules.

“There was insufficient evidence to determine whether the failure to initiate an alcohol withdrawal protocol or a sooner initiation of CPR would have prevented the death,” the review board wrote.

No better outcomes

The San Diego County Sheriff’s Department hires outside vendors to provide much of its health care to jail inmates. In addition to mental health providers, the sheriff contracts with physicians, hospitals, dentists, drug providers and laboratory services.

In fiscal 2017-18, the most recent for which data were available, the department spent $31.8 million on health care contracts. Four years prior, in 2013-14, the sheriff’s health care contractors were paid $36 million, records show.

Sheriff’s officials said overall health care spending is notably higher than what is paid to contractors. Last year, the department spent $83 million on inmate health care, much of it on staffing and supplies. That’s up from $76 million in 2016-17 and $54 million a decade ago.

Increased spending did not always translate to better outcomes.

According to its own records, the department spent $1.6 million on mental health contracts in 2009-10, when two inmates killed themselves while in custody. In 2015-16, eight inmates committed suicide despite $4.5 million in spending on mental health contracts.

For the fiscal year that ended June 30, the sheriff budgeted $5.4 million for mental health services. At least three inmates have taken their own lives since July 2018.

With government contracts, performance is supposed to be supervised and corrections made to ensure public investment is not wasted.

According to court records, some county officials believed the jail’s former mental health provider did not properly manage or train the psychiatrists who were hired to treat jail inmates.

“CPMG’s lack of control on the psychiatrists and lack of standardization for clinical practices has put the department at extreme risk from a legal standpoint and sheriff’s Medical Service Administration has had to take action based on CPMG’s failure to correct clinical care issues,” Joshua, the sheriff’s former medical director, wrote in an undated termination notice.

“Eight CPMG providers had to be removed by the sheriff’s Medical Service Administration with six more CPMG providers on notice to be removed,” he added.

“Most importantly – on a grand scale – the emails show a systemic and intentional failure to train providers on suicide prevention and to address quality care issues. The emails themselves suggest a pattern of deliberate indifference.”

— Lawsuit against the county by the Nishimoto family

The correspondence came to light in December, when lawyers for the county provided attorneys in the Nishimoto case with the documents as part of a discovery request. The records exposed a fraught relationship between the county and its mental health contractor.

“If you were concerned about the quality and clinical effectiveness of CPMG rather than how much is achieved to its bottom line, you would know the following:” wrote Joshua, who then typed out a litany of errors in the Nishimoto, Nunez and Moriarty deaths.

The recently unsealed records show CPMG was awarded the contract in 2014, when the company was brand new and its owner had no experience in correctional psychiatry.

The court documents — ordered unsealed after the local American Civil Liberties Union intervened in the case — also showed that show CPMG and the county requested that the documents be sealed, making it harder for the public and plaintiffs’ attorneys to see the underlying claims about lapses in patient care.

Mannis and his lawyer declined to respond to questions from the Union-Tribune regarding the spate of deaths while CPMG was under contract to provide psychiatric services to the jails. But in a August 2016 email to county officials, Mannis said the company needed more help.

“CPMG feels that there should be more mental health providers for therapy/ intake which I recruited for and was ready to start this program,” he wrote. “The psychiatrists in CPMG are well trained providers. I am sorry that you put all the blame on CPMG as there are many issues involved.”

By January 2017, the county canceled its agreement with CPMG and awarded a no-bid contract to a national provider called Liberty Healthcare Corp. The Sheriff’s Department declined to explain why the arrangement was not put out for competitive bidding.

Joshua, who resigned as the sheriff’s chief medical officer on June 30, 2018, did not respond to requests for comment about CPMG or inmate health care services.

Experts say corrections work is difficult. Conditions can be stressful, and some inmates can be violent. Guards tend to respond to safety concerns first and are not always paid enough to appreciate and respond to mental health issues.

“Let’s say an officer sees a jail resident smearing feces in his cell. The appropriate response is for that officer to say, ‘Oops, I think we have a problem. Let’s do something about it’,” said Marc Stern, a University of Washington professor and expert in corrections health care.

“But if that officer is underpaid, under-trained, or is the wrong person for the job, we may get a different response with a more devastating outcome.”

Aaron Fischer, a lawyer with Disability Rights California, a Sacramento advocacy group that last year studied suicides inside San Diego County jails, said deputies have made little progress at improving health care and mental health treatment.

“Custody is (still) driving decisions, and that’s a problem,” Fischer said. “There’s insufficient clinical input into key treatment decisions for people held at the jail, including where they’re going to be housed.”

He said, no matter what situation a mentally ill patient is facing — treatment or lack of treatment — jail will make things worse. The smallest change in setting, medication, counselors or routine can upend their well-being, Fischer said.

Union-Tribune data analyst Lauryn Schroeder contributed to this report.

Next installment

Tuesday: Jail deaths are routinely investigated, but public findings are hard to come by

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.