California Memorial Project: Remembering those who were forgotten

California Memorial Project: Remembering those who were forgotten

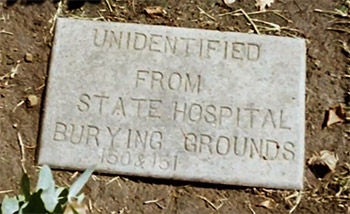

The California Memorial Project (CMP) seeks to honor and restore dignity to individuals who lived and died in California state institutions. From the mid-1800s to the 1960s, it is estimated that more than 45,000 individuals died while residents in state institutions. For the most part, the remains of the individuals were placed in unmarked or numbered graves in mass sites, where numbered markers long ago disappeared. Many records identifying where bodies were buried have been misplaced or destroyed.

The California Memorial Project is a collaborative effort co-founded in 2002 by DRC’s Peer Self Advocacy Unit, People First of California and the California Network of Mental Health Clients. In 2002, Senate Bill 1448 (Chesbro) created the California Memorial Project (CMP) and established a task force to identify the names of people who were buried at state hospitals and developmental centers and to locate and develop a plan to restore gravesites on facility grounds. In 2010, Assembly Concurrent Resolution 123 (Chesbro) proclaimed the 3rd Monday of each September as California Memorial Project Remembrance Day. Ceremonies are held on that day throughout the state on the grounds of current and former state institutions, including a statewide moment of silence to honor people who lived and died in these institutions without the acknowledgement and respect they deserved.

The California Memorial Project is a collaborative effort co-founded in 2002 by DRC’s Peer Self Advocacy Unit, People First of California and the California Network of Mental Health Clients. In 2002, Senate Bill 1448 (Chesbro) created the California Memorial Project (CMP) and established a task force to identify the names of people who were buried at state hospitals and developmental centers and to locate and develop a plan to restore gravesites on facility grounds. In 2010, Assembly Concurrent Resolution 123 (Chesbro) proclaimed the 3rd Monday of each September as California Memorial Project Remembrance Day. Ceremonies are held on that day throughout the state on the grounds of current and former state institutions, including a statewide moment of silence to honor people who lived and died in these institutions without the acknowledgement and respect they deserved.

Sharing experiences with someone who can relate: the Peer Self-Advocacy program

In addition to leading DRC’s work on the California Memorial Project, our PSA staff also knows that having staff who have similar experiences and feelings is a powerful tool to help people with mental health disabilities learn about their rights. That is the foundational principles of DRC’s Peer Self-Advocacy program (PSA). “Since we are all peers, PSA staff members provide and facilitate peer support while teaching self-advocacy.” The program became a separate unit within DRC in 1995. In 1997, PSA had staff in each of the organization’s offices – Sacramento, Oakland, Los Angeles and San Diego. The PSA has eight advocacy staff throughout the state.

From the beginning, the PSA’s goals have been to:

- Help people understand their human, legal and service rights

- Help people learn to exercise their rights to get what they need

- Provide training and technical assistance to self-advocacy groups as they develop and implement advocacy projects.

For example, the Patton Advocacy Group on the West Compound developed a Patton State Hospital Peer Self-Advocacy Book called, “Putting Yourself in the Driver’s Seat.” Group members created the guidebook with illustrations to help other self-advocacy groups throughout the state. The Deaf Community Clubhouse self-advocacy group in San Diego met with Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) staff to express their disability-related needs and suggest changes in DMV services. The DMV agreed to a future meeting to address their concerns.

“We focus our work on teaching people how to advocate for themselves rather than providing direct advocacy for them,” said Gantsweg. “By training people to advocate for their own rights, the PSA program empowers and equips them to identify their goals and develop action plans to accomplish them.” The PSA helps peers start their own self-advocacy groups and conducts peer self-advocacy trainings in locked mental health treatment facilities as well as in the community. By doing this, they provide skills, strategies and tools to help people become successful self-advocates.

For example, UCLA student Taylor Tabbut used the self-advocacy tools she learned through PSA to help fellow college students get the services and support they needed from the university. She served as president of UCLA’s National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) On-Campus Chapter. “I’m trying to create an environment where people treat others with compassion and understand their differences,” she said. That passion and dedication earned Taylor a Client Recognition Award from the DRC Board of Directors in 2016.