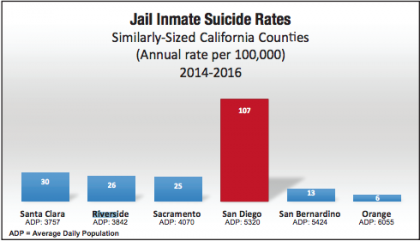

Inmates in San Diego County’s jail system commit suicide at much higher rates than inmates in other similarly sized California counties, according to an investigation by Disability Rights California.

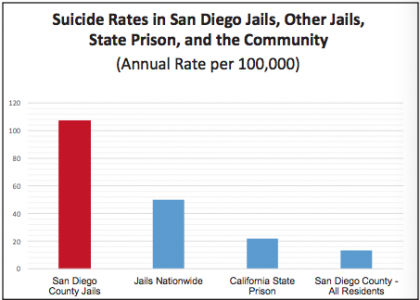

Since 2010, more than 30 SD County inmates have killed themselves, according to the report. Between 2014 and 2016, 17 people died by suicide in the county’s jails. San Diego, with an average daily jail population of 5320, averaged 107 in-jail-custody suicides per 100,000 during those three years. The jail suicide rate was nearly eight times the suicide rate for the county as a whole (13.1 for every 100,000 residents). Orange County, with an average daily population of 6055 had one suicide during the three-year period–or 6 deaths per 100,000.

SD County asked DRC to use a different method than the U.S. Department of Justice’s method of calculating the per 100,000, saying that it did not factor in the county’s unusually high percentage of white inmates, who are statistically more likely to commit suicide than inmates of color.

However, according to DRC, “the fact that San Diego County may have a higher-than-average number of inmates at elevated risk of suicide only adds urgency to the need for action.”

Riverside (daily jail population of 3,842) and Sacramento (daily jail population of 4,070) each had three inmates commit suicide. And in Los Angeles County, where the jail population is more than three times that of San Diego’s, there were 8 suicides–less than half the number recorded in San Diego.

Fourteen of the 17 people who killed themselves in SD jails “had a clear history and indication of mental health needs”—including having histories of past attempted suicides, according to the DRC investigation.

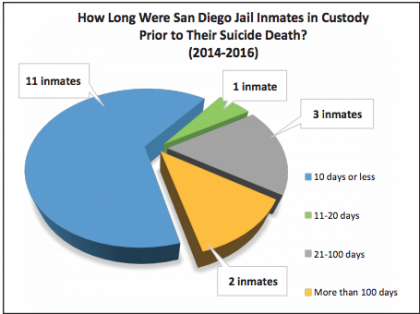

Nine of the inmates were in jail on non-violent charges. Fifteen were not in jail on a conviction. Rather, they were locked up while they awaited trial. Eleven of the inmates were in jail for 10 days or less at the time of their death. At least six people were in solitary confinement when they died. “Several more were in units that we observed to have solitary confinement conditions,” the report’s authors state.

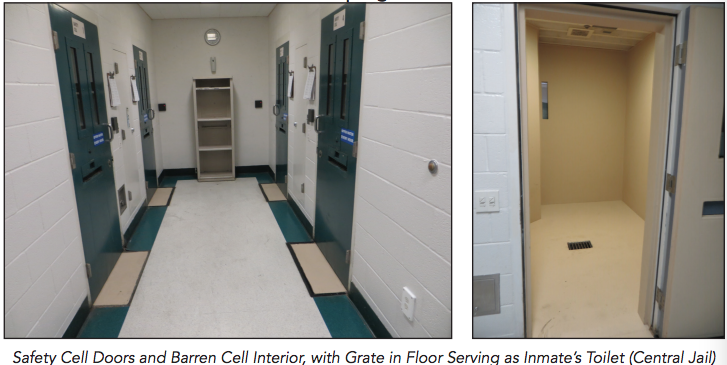

“Every day hundreds of men and women face solitary confinement, which has contributed to the high number of suicides and suicide attempts each year,” said DRC Litigation Counsel Aaron Fischer. As one woman wrote while locked down in her cell: “This treatment is worse than people treat animals…being locked in jail inside a box inside of another box can do things to a person’s mental state.”

DRC employed the expertise of Dr. Karen Higgins, who previously served as the lead psychiatrist for the Denver City and County Jail system, as well as the statewide Chief Psychiatrist for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). The DRC’s second expert, Dr. Robert Canning, spent 10 years as the CDCR’s statewide Suicide Prevention coordinator, “chairing the statewide suicide prevention committee, designing mental health and suicide prevention trainings, leading suicide prevention policy reforms, and building CDCR’s quality improvement systems.”

After analyzing the records for all suicides occurring between December 2014 and December 2016, and reviewing the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department’s jail policies, Higgins and Canning developed a list of 24 “key deficiencies” regarding suicide prevention in the jails. To address these deficiencies, the duo drafted 46 recommendations to improve mental health care and prevent suicide behind bars.

In 2015, the sheriff’s department started working to address its high suicide rates. The department implemented an “Inmate Safety Program,” which updated mental health policies and training for custodial staff. It also created housing specifically for people with signs of suicidality. But in 2016, the jails’ suicides remained high. Then, in 2017, a San Diego Grand Jury issued a report on the county’s colossal suicide rate. The jurors praised the department’s efforts to curb suicides, but called for further improvements to oversight, training for jail staff, and more. San Diego Sheriff Bill Gore responded, saying that his department would follow through with the grand jury’s recommendations. In its report DRC praised Sheriff Gore’s commitment to reducing suicides in the jails, but said that there are still “many aspects of the system’s treatment of people who have mental health needs, or who are at risk of suicide, that require urgent action.”

According to the DRC’s two experts, the sheriff’s department must improve screening for suicide risk when inmates are booked into jail, and “at key transition events that carry elevated risk (e.g., placement in solitary confinement), and at other high-stress, high-risk moments (e.g., inmates receiving “bad news” about their criminal court case, moving to prison, or being extradited).” In one of the individual cases that Higgins and Canning examined, upon his arrival at jail, an inmate was exhibiting “symptoms of florid psychosis and mania.” Instead of being sent to the Psychiatric Security Unit, the man was placed in solitary, where he died by suicide several days later, without having been properly screened for suicide risk.

More than six other inmates died in solitary or in solitary-like conditions. “The placement of inmates particularly those with mental health needs, in segregated or restrictive housing increases the risk of suicidal and self-harming behavior, isolates individuals, and impedes normal interpersonal interactions that are essential to psychological health and adequate treatment,” the report says. The sheriff’s department does not adequately screen inmates for suicide risk before placing them in solitary, Higgins and Canning conclude. One inmate spent more than five months in solitary and the jail’s “safety cell”—a small, padded, empty room—before committing suicide.

Another man in solitary was only allowed out of his cell for one hour every 48 hours. The man requested psychiatric care two days before he was found hanging in his cell, with urine on the floor, food and feces on the ceiling, and a suicide note, written in blood, on the wall.

And when custodial staff catch an attempted suicide, “staff’s emergency response will often determine if the person lives or dies,” according to the report. But, “in nearly half the emergency responses to lethal suicide attempts they reviewed, poor coordination of lifesaving efforts, delays in starting CPR, and/ or malfunctioning medical equipment.” In one case, deputies delayed for seven minutes after finding an inmate hanging, and then did not allow nursing staff to evaluate the inmate or use the defibrillator to try to revive him.

The experts also took issue with custodial staff’s failures to monitor inmates in isolation to ensure that they are not attempting to harm themselves.

Higgins and Canning also found that the jails do not provide inmates with “adequate individualized mental health treatment” plans, a deficiency which the experts say violates state law.

The report also called on the sheriff’s department to improve communication between the mental health care staff and custodial staff regarding inmates’ mental health status. “In one case, a man died by suicide the day before his transfer to another state to face criminal charges,” the report states. “The DRC Experts found that custody staff knew he had made a credible suicide attempt a few weeks earlier, and that he was experiencing considerable stress about being extradited. Yet the inmate’s treatment record did not reflect any sense of heightened risk requiring closer observation, monitoring, and clinical follow-up.” According to Higgins and Canning, this death may have been prevented by better communication within the jail system.

The sheriff’s department’s suicide prevention training, too, is lacking and must be updated, according to the report.

“While the County has in recent months taken affirmative steps to enhance its suicide prevention training program in the wake of the Grand Jury’s 2017 findings, the DRC Experts found that the County’s training program is not well coordinated, tracked, or evaluated,” Higgins and Canning found.

Additionally, the department reportedly does not properly review suicides. “It is problematic that the Sheriff’s Department Critical Incident Review Board does not conduct a formal review of all serious suicide attempts,” the report states. “This is a missed opportunity to learn from experience and to strengthen policy, procedure, and training moving forward.”

The two experts also took issue with the San Diego County Citizens’ Law Enforcement Review Board (CLERB), finding that the independent oversight body does not “serve a meaningful or sufficient role in the provision of external, independent oversight with respect to suicide prevention.”

The sheriff’s department has cooperated fully with the DRC investigation into jail conditions. “We firmly believe the jail system’s leadership is committed to addressing the crisis of inmate suicides and improving conditions,” said DRC’s Aaron Fischer. “However, the county needs to step up to provide the resources and accountability necessary to solve what are serious, longstanding problems.”

[…] View Reddit by Whey-Men – View Source […]